Ken Lloyd Gruffydd

Introduction

During May 1837 local and national newspapers reported a mining tragedy on the outskirts of Mold.

The Chester Chronicle ( 30 May ) ran :

an accident dreadfully fatal in its consequence occurred at the Argoed Hall Colliery, near to this town, on Wednesday morning last, the 10th inst., by which awful calamity twenty-one lives were lost, eight widows left desolate, and about thirty children left orphans.’

As the name implies the coalmine was situated on the lands of Argoed Hall, some fifty feet above the river plain of the Alun, and operated by a group of Liverpudlians under the dual name of Hampton & Company, or, Argoed Hall Colliery Co. It was a small undertaking consisting of two main shafts, the lowest of which had a 16 horse power steam-driven fire engine installed to rid the workings of accumulated water. We are not told how deep this particular pit was but such machinery was generally used at depths exceeding 30 yards.

Mold at this time was in the throes of the Industrial Revolution, possessing numerous manufactories that included a large cotton factory employing over three hundred people. The surrounding hills were dotted with leadmines and within a mile from the town itself half a dozen or so coalmines provided work for hundreds more; Argoed Hall Colliery having 60 colliers on its payroll.

A commission set up by the government in 1841 to discover the conditions of employment of children noted that those hired at the neighboring Argoed Colliery usually worked 12 hour shifts, from 6.00am to 6.00pm and were paid a derisory amount for their efforts. Not surprisingly they were considered a hardened lot, ‘a ruder set than other working boys’. Local ministers of religion and Justices of the Peace called to give evidence were of the unanimous opinion that their uncouth behavior could be attributed directly to their upbringing. Unlike leadminers who, for the most part, dwelt in isolated cottages away from their place of work, the colliers inhabited streets where practically every house was occupied by employees of a particular colliery. They socialized together in places where drinking, smoking and the use of bad language was commonplace. It was stressed that the long working hours endured, and non-attendance at schools, promoted ignorance and stinted growth amongst the young! The Revd. Isaac Harris, minister of Bethel the Independent Welsh Chapel was, however, quick to point out that the vast majority attended divine services and Sunday schools. Similarly, the parish’s Relieving Officer emphasized that members of this sector of society were generally healthy, supportive of their families, even when in sickness, ‘and there is generally a medical man engaged to attend them, who is paid by a poundage on wages.’

The Clerk of the Petty Sessions revealed that the distribution of colliers’ wages was not always forthcoming. There were times when the court heard workmen and children complain of long overdue payments. These delays could sometimes go on for months, and since the relevant paperwork was often ‘indifferently kept’,disputes ended up before the bench. It was disclosed that in many instances colliers were obliged to :

meet the chartermasters at a public house, where the wages are paid, and where a great deal of money is often spent. The public houses they frequent are often of the lowest order, and the settlement being on Saturday night. It is not an uncommon thing for some of the men to remain all night, and even all Sunday, in these houses, where the greater part of the wages were consumed, to the great detriment of families.’

In contrast, management regularly paid their foremen promptly, in full, and at the site office. Families at this time lived very frugally on limited budgets. They practically existed on a diet based upon bread and potatoes, while boasting about the consumption of meat on Sundays. When snappin ‘packedfood’ was taken underground it generally comprised of bread, a lump of cheese or suet and a canister of water. Very often they had to buy their own tools and candles. Despite growing objections by social reformers about parents sending their offspring to carry out strenuous physical work for unwarrantedly long hours, a good number ignored their pleas in order to supplement their own low wages. About a quarter of those working at the Argoed Hall Colliery on that dreadful day were

aged 16 years and under, the youngest being 9 years.

The principal means of extracting coal in this district was known as the pillar and stall method whereby a series of parallel stalls ( 3 yard wide roadways) would be driven some 3 yards apart, going in for some 6 yards before they were left as pillars ( rectangular columns ) to support the roof from falling in. Unlike the neighboring Argoed Colliery where accidents due to concentrated pockets of gases had been numerous since its opening, the Argoed Hall concern had been free of serious incidents.

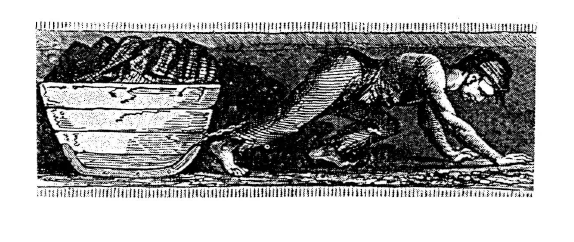

Working conditions in most mines hereabouts were exceptionally hard due to the thin, heavily-faulted and steep-angled nature of the seams; some in excess of 20 degrees. The colliers and their putters ‘young helpers’ were therefore forced to labour in cramped environs, on their knees or even on their backs, as some bands were less than 2 feet thick. At the Argoed we are told of :

‘Sledges drawn by Boys, bringing the coals out of the workings to the crosses, and are then

drawn onto the flat frame of the trolley , moving with 6 inch wheels upon an edge rail way. Rarely was there a flat rate for working, hewers’ wages being determined by how much coal they extracted in a week, generally dependent upon the geological structure of the section being mined. The rate per ton ( 20 cwt) at this time was about 1s.0d. while the young putters who drew and pushed sledges and trucks only pocketed 6s.0d. for toiling a 72 hour week. It was against this background that the colliery accident occurred and rescue missions undertaken. [ For Location Map of colliery see back page. ]

Sequence of Events

Wednesday, 10 May

Thomas Roberts and John Kendrick, both Sychdyn men, had got up before dawn to walk the two miles in dim light to the colliery at Argoed in order to begin the early shift at 5.00am. Kendrick, a collier of fifteen years experience was only in his second month at the mine, being previously engaged at the neighboring Rhydgaled Colliery. Descending in the first tub to be lowered that morning they reached the bottom o f the Engine Pit and walked some 600 yards to the coal face where they worked, probably in partnership, with young boys undertaking sledging the coal to nearby wooden-railed trucks, and hence, to the shaft where it was raised to the surface. Then were very much aware that for the previous four days water had been seeping into the Bye Pit – at the other end of the colliery; – at an increasing rate after drivings to the north-east of it had broken into a drowned mine abandoned c. 1772. Anticipating a deteriorating situation the underground agent, John Owens, had suspended operations in that section and only employed four men there to repair walling and clear the roadways. Concern was now shown for the main shaft, or Engine Pit as it was known, which was at a lower level and water had already begun to run into it. To their relief Roberts and Kendrick noticed that the steam-engine used in raising excess water was only running at its normal ‘snore’, informing them that working conditions were not too wet underfoot. Thirty-nine went down the pit that morning, amongst them ten boys aged sixteen and under. They had been working diligently for about an hour when one of the youngsters called in panic that they were in danger of their lives. After scurring about and shouting for a minute or two the experienced colliers assessed the situation as safe and that it had been a false alarm; not an altogether unusual occurrence when children were involved in the underground darkness.

It was also about this time that the undermanager arrived in the Bye Pit to review the situation regarding the leakage and how the four men he’d assigned to that part were progressing. The conditions underfoot had certainly deteriorated but were not critical and at 8.00am he left for the surface to get his breakfast. In his deposition to the Court of Inquest later he said that ‘a number of the labourers, being somewhat alarmed’

followed him as they were perturbed that the water level was now increasing. Owens returned at 10.00am with a small group of men to inspect the trouble-spot. When within 40 yards of i t , they heard the loud rumbling of rushing water. Without hesitation they turned-tail and ran for their lives to the Bye Pit shaft, at the same time shouting for those at the surface to haul them us as quickly as possible as the water had broken through. They also encouraged them to send word to the Engine Pit. They were joined at this stage by two young men who were at the time repairing the air-shaft situated between the two pits, and by another who saved his life by scrambling up one of the pipes that took excess water to the surface. It was the latter who ran to the colliery office to sound the general alarm A wall of water gushed into the Bye Pit with such a force that it ‘dashed against the further side … and rebounded back again’ before flowing in strength downhill towards the Engine Pit, the coal rise being one in three. Sixteen worked the extensive workings west of this shaft and in a few seconds found themselves knee deep in black liquid, and within a couple of minutes, all but five of them were cut-off from any means of escape.

Four of the five who d id succeed did so at great peril to their lives as they were carried by the current for some 22 yards, eight of which they survived submerged underwater. Three of them were named in one newspaper account as ; John Ithel, John Jones and Edward Williams. They were conveyed up-top by the winding-engine.” The unlucky ones were reckoned to have drowned in a very short space o f time.

When the crucial warning was relayed to Thomas Roberts, John Kendrick and others in the far reaches of the mine they immediately downed tools. The decision was quickly taken for them to proceed to a nearby ventilating shaft up which they could escape to the main level. They quickly realised, however, that their way forward in that direction was blocked by advancing water. The only alternative was to aim for the Engine Pit, a good distance away. For a while they were convinced that they had made the correct decision but some hundred yards short of their objective they found their escape route was barred by water up to roof-level. The most experienced amongst them knew immediately that they were trapped. The first to comment on their plight was Robert Owen of Maes-y-dre, father of the future novelist Daniel Owen. Mis, ‘ W e l l , well lads, it’s all over for us,’ brought an angry reaction from a couple of his contemporaries. On the other hand John Jones of Glanrafon philosophically remarked, ‘ I f that is the case Robert, then we should prepare ourselves for death!’ At which point they began a prayer meeting, and from what we have learnt from survivors, most o f the proceedings look place in the Welsh language. Daniel Owen’s 11 year old brother Robert, described as ‘a good singer’ led the singing of O Fryniaii Caersalem ceirgweled . Neither he, his father, nor his ‘seriously-minded and religious’ older brother Thomas survived. In the meantime, a reduction in oxygen caused most of them to fall asleep. This was especially true of the children who appeared to be completely confused and disorientated. Indeed, they were perplexed to such an extent that ‘some took off their clothes as if preparing for bed, and spoke as though they were at home with their families.'[11 The speedy accumulation of foul air may well account for the vague

recollections the little ones had of their underground experiences. They were forever hungry and on two occasions pieces of bread were found for them in the men’s pockets, Thomas Roberts being one of them said, ‘but I ate nothing.’ There was even one instance when, in pitch-black circumstance, some of them mistook a soft lump of stone as bread and ate much of it! The Colliery Secretary, Owen Jones [2], who later wrote an account of the disaster, noted that throughout the day officials and employees were practically demented by the knowledge that thirty-one of their own were entombed below and that their efforts at rescue were proving futile. News of the emergency spread like wildfire through the surrounding countryside and beyond. Thousands were said to have rushed to the hillside above the colliery to await any news, amongst them ‘hundreds from Mold market’, some curious as to developments others to console the families o f the lost ones who were unashamedly crying aloud From early afternoon onwards pleas for help from neighboring pits [3] were responded to post haste.

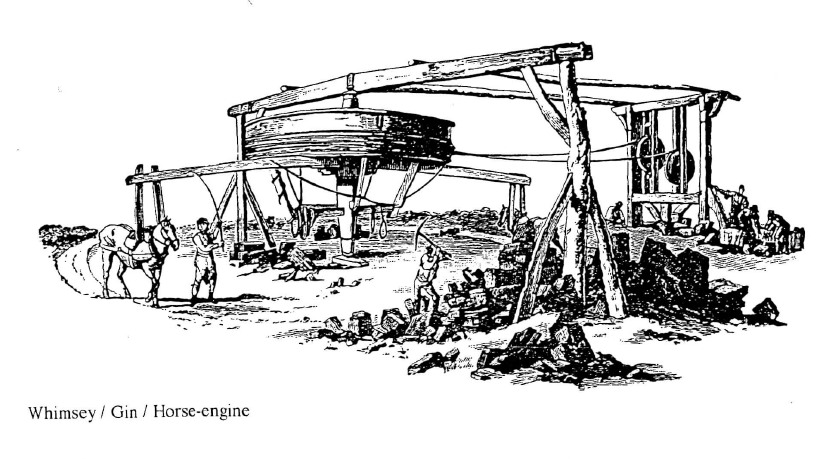

Two additional whimseys were immediately forthcoming and set up at the head of each main shaft in double-quick time to assist in the pumping of water out of the pits, the steam-engine on its own being inadequate to the task. Owen Jones recorded that the ‘kindness shown to us by the neighbourhood for a 3 mile radius was second to none, by the gentry, farmers and businessmen who gave use of their horses, day and night, for a fortnight.’ By the end of that first evening of imprisonment the colliers’ situation had worsened as the water-level in the Engine Pit had reached 15 yards up the shaft.

Thursday, 11 May.

The 16 h.p. steam-engine was operated at full power throughout and the horses drawing the whimseys changed regularly. From early morning the surface area was a hive of activity with colliers from other pits in the district arriving in their droves to offer their professional help. Records don’t tell us whether they had been sent by their respective employers or had personally volunteered their services. That evening the level of water ceased to rise, probably because a team of carpenters had been all day constructing additional wooden air-pipes to run down a ll the shafts. These were coupled to hand-operated bellows-type machinery borrowed from neighbouring pits and known as forcers , their function being to force down fresh air to displace the putrid atmosphere encountered below ground.

Those underground were slowly coming to terms with their hopless predicament. Even the old hands were despondent since they could hear no noise whatsoever coming from any direction. Occasionally, one would imagine that he heard a sound and all would be quiet, anticipating the knocking and calling of rescuers.

Sometimes, thinking that they heard such a response, they shouted out at the top of their voices but to no avail. .Most of the candles died out during this day.

Hopeful onlookers occupied the nearby hillside all day and during the evening the crowd expanded to several hundreds. Many of the relatives and friends were elsewhere, at the Baptist Chapel, attending a multidenominational prayer meeting where the atmosphere was both exceptionally moving and electric. Some of those directly involved in improving underground conditions were later adamant that the water stopped rising at about the same time as the religious gathering was taking place. They could not be convinced otherwise.

Friday, 12 May.

It is uncertain whether it was during the previous evening or the early hours of this morning that Robert Owen of Maes-y-dre, his son of the same name, John Jones of Sychdyn and his lad Richard, stumbled through the darkness to seek drier ground. Whatever the truth of the matter, it proved a fatal decision, as they were not long

afterwards believed to have been overcome by sulphuric poisoning and died.

At some point in time during the late afternoon the more experienced colliers sensed that they were inhaling purer air than had previously been the case, and when they began to feel a slight breeze on their cheeks, they knew it to be a fact. Having ascertained the direction i t was coming from they slowly and deliberately groped their way through the waist-deep water. Meanwhile, the surface supervisors had sent a team of the strongest available men to carry out the latest survey work. On reaching the level next to the Engine Pit’s shaft they realised that the flooding had subsided dramatically, and immediately decided to make their way to where survivors were likely to be stranded. It wasn’t long before the, by now tired and isolated colliers, heard faint noises of rescuers digging towards them from an upper level. They responded spontaneously by knocking stones on a coal truck and yelling their heads off for the helpers to hurry up. The cry of, ‘Some of them are alive!’ echoed all the way to the surface where the ever-present crowd rejoiced in a scene of mad merriment:

‘The news spread like wildfire to the fair i n town and within a matter of minutes the town was practically empty, with the roadway..to the colliery full of people, ,

so that when they had all arrived at the site they numbered between four and five thousand.’

The time-lapse between the initial communication of the two groups, the breakthrough and ultimate rescue no doubt felt like an eternity for the ten that were brought to the surface around 6.00pm that evening. We are told that they had been prisoners to the ‘east’ of the Engine Pit. Before the sun set another two were brought up dead.

Thomas Bellis, aged 18 years, and a 9 year old Pentre boy whose fate is best described by his would-be rescuer,

Thomas Price of Bromfield Colliery :

‘We then set more air-pipes and getting a few yards further on I heard a person groaning.

I went forward and found the lad Hugh Parry, lying on his back, in a state of great exhaustion, and earned him in my arms to the mouth of the pit, but he died on the way.’

The ten that were saved that day were :

John Kendrick – married man from Sychdyn

Thomas Roberts – married man from Sychdyn

John Evans – young man from Bryn-y-bal

Daniel Jones – young man from Maes-y-dre

Edward Kendrick – young man

Robert Minshull – teenager

Hugh Jones – aged 11

James Jenkins – teenager

Roberts Ellis – aged 10

Henry Hughes – aged 12

The latter five boys were said to have been exhausted with Henry Hughes’s condition, of whom we shall hear later, being described as yn llesg iawn ‘very weak’. A report described the majority, even the men – after hunger and prolonged exposure to cold, wet conditions – as close to perishing. On their arrival at the pit’s mouth they were immediately attended to by a team of local practitioners who diagnosed the best method of treatment for each individual before they were raised to the surface in twos, whereupon ,

‘A little weak broth or gruel was given to them, and they were removed to their homes in light carts, with straw over the bottom, the people of the surrounding cottages bringing the blankets from off their beds in which to wrap them.’ Each of the survivors was accompanied by a doctor to advise the relations as to how best to take care of them, and what action to adopt in order that they fully regained their health.

Saturday, 13 May.

With the water-level continuing to fall the rescue teams were greatly encouraged to strive that much harder but during the morning the good news of having discovered another air-pocket quickly turned to disappointment when five bodies were found; one of whom, Thomas Ellis, being described as a ‘pauper’ with a large family and one who had only been employed at the colliery some three days. His son Robert was one of the lucky ones to be

saved on Friday, while his eldest was the first to escape top-side and give the initial warning o f an impending disaster. The dead were listed as follows :

Daniel Jones – of Mold, young man

William Williams – of Bagillt, young man

John Owen – kept his widowed mother

Thomas Ellis – of Mold, left a widow and’large’ family

Robert Owen – of Maes-y-dre; aged 37 and father of . .. Daniel Owen.

For Robert Owen to have been retrieved from amongst this group of people makes one suspect that he was somehow separated from his original company, or, was forced to abandon them after they had all died. We are told he could swim. During the evening three more bodies were recovered and the hope that there were others still alive diminished by the hour. They were named as :

John Jones – of Sychdyn Mountain, left widow and 3 children

Richard Jones – of Sychdyn Mountain, son of above

William Hopwood – of Mynydd Isa, left widow and 4 children

John and Richard Jones were father and son and found in each other’s arms. Hopwood was said to have been middle-aged with four children, two from his present marriage and two with a previous spouse. The list of dependents losing their breadwinner was increasing by the day.

Sunday, 14 May.

The Church calendar recorded this day as Whit Sunday but to Mold worshippers it was seen as a ‘ Black Sunday’. It was estimated that during the morning thousands of sympathisers, the curious, and religious groups congregated in the vicinity of the mine, some o f them having travelled as much as twenty miles. Those who took the most prominent part were said to have been the Weslayans of Hawarden parish who, from 11.00am onwards, addressed the crowd on serious religious matters, emphasising the importance of repentance and that everyone should be prepared to meet his Maker. In the afternoon they took advantage of the attentative onlookers by distributing English and Welsh pamphlets amongst them : The Life of James Covey, Gweddiy Tyngwr, Dirgetwch i ‘r rhodianwr ar y Sabbath , etc. Despite sending more rescue teams down no survivor nor dead colliers were brought up this day – but there was a growing hope that the situation would soon improve

Monday, 15 May.

This proved to be a disappointing day but not an uneventful one. Work in clearing roadways, securing walling and replacing roof-props continued unabated but the water-level did not recede sufficiently for them to make any further progress towards the trapped men. An inquest on the first bodies brought to the surface on Saturday was held at the Shire Hall under Mr. Parry, the County Coroner. He advised the j u ry to bring in a verdict of manslaughter against the proprietors, or their agents if, in their opinion, Messers Hampton & Company had been negligent in their operating of the colliery. The twelve just men responded by declaring the employees’ deaths to have been accidental, caused by

asphyxia due the inhaling of ‘foul air’. They went a step further by aquitting the owners and their officials from ‘any blame or neglect, connected with the breaking in o f the water.’

Tuesday, 16 May.

On this day, with the shadow of litigation having lifted, a group of prominent local gentry attended a public meeting at the Black Lion Inn, Mold, to see what could be done to alleviate the forseen hardships that would soon be experienced by parents, widows and some thirty orphans. The gathering was chaired by John Wynne Eyton of Leeswood Hall. Six resolutions were passed, the most significant ones being the setting up of a public subscription for the relief of the victims’ dependants, and also, to award gratuities to certain heroic rescuers. The appeal was to be announced in both local and national newspapers that included the Times ,and special donation accounts were to be opened at specific banks throughout England and Wales. The money was to be finally held and administered by Messers Douglas and Smalley & Co. Bank which had its branches at Holywell and Mold. The fifty-eight attending that first meeting promised the noble sum of £225.1 ls.Od.

Friday, 19 May.

The progress of clearing the rubble and debris in order to precede towards the remaining eleven trapped workers continued from the upper levels as the water in the Engine Pit was still up to roof-level. It was now nine days since the accident and hopes of finding anyone alive were considered extremely slight, the experienced colliers having long since expressed the view that the principal danger came from poisonous gases, and not from the flooding. Their fears were realised on this day when the bodies of two men and two boys were discovered :

Thomas Jones – of Mynydd Isa

John Jones – of Mold

Robert Owen – of Maes-y-dre, 11 year old brother of Daniel Owen

George Wynne – 15 years old

A l l of them described as ‘God-fearing people, ever faithful at their churches.’

Wednesday, 24 May.

It had taken a further five days before the water had subsided sufficiently for the colliers to be able to descend to the working level of the Engine Pit. They found no one there.

Thursday, 25 May

Four further corpses were brought to the surface :

Thomas Jones

Thomas Mathews

Mathew Mathews

Thomas Owen

They were discovered at ‘Plygain’ ( about 7.am ).

Friday, 26 May.

Two more were found : Thomas Hughes – middle aged, left widow and 7 children

Thomas Harries – of Sychdyn, left a widow and 4 children

Saturday, 27 May.

In the afternoon the twenty-first and last person’s body was retrieved from under a roof-fall.

William Jones – of Maes-y-dre, recently married

Monday, 29 May.

A special non-denominational Rememberance and Thanksgiving Service was held at the Calvanistic Methodists’ Bethesda Chapel in New Street. [4] of Sychdyn, young man of Mold, young man of Mold, young man of Maes-y-dre, aged 16, brother of Daniel Owen

Aftermath

Before the end of the year the Trust Fund set up for the victims and their dependants had reached a sum in excess of £950. No information has survived to tell us how, if any, payments were made. That allotted to Daniel Owen’s mother was 14s.Od. per week until her son (7 months old at the time), was aged 14 years. We do know, however, that in 1837 there was an economic crises in Britain that resulted in many banks going to the wall.

For a period Messers Douglas & Smalley Co’s bank remained solvent but the major partner – John Douglas of Gyrn Castle, Llanasa, who was heavily involved in the cotton industry : went bankrupt soon afterwards, and so did the bank. We can only imagine the effect this had on the surviving dependants of the dead colliers. In a short biography Daniel Owen describing his mother, states that following the death of her loved ones, ‘she nearly went

out o f her mind for many weeks, getting up every hour of the night… and opening the window expecting to see them coming home from work.’ Oral tradition ( often suspect) tells us that Sarah Owen took in washing in order to sustain her remaining four children and this is bome out by the 1851 Census where she is described as ‘Pauper Mangier’. Twenty years later she appears as ‘ Mangle Woman.’ In his novel Rhys Lewis the author is obviously reminiscing about his mother when describing the actions of the character Mari Lewis

My mother sold various small pieces of furniture that we could spare; but she took care that the buyers were strangers. I knew she dreaded being considered poor by the chapel members….’

There is also a claim that she spent time working at the Mold Cotton Company’s mill. We must treat this last statement as unproven, but possible.

A true and sad story is that of John Jones of Mynydd Isa who was one of the three who escaped up the Engine Pit shaft as the colliery Hooded while his brother was not so fortunate. His traumatic experience resulted in him becoming a total abstainer and was pre-occupied with his own survival to such an extent that it developed into an obsession. He turned to religion for solace and was forever announcing that he was unworthy to have been ‘saved’ while better citizens had perished. We are told that on one occasion he was said to-have been very vocal in the High Street, openly addressing his feelings to God. A non-Welsh speaking constable was about to arrest him for disturbing the peace when local tailor Angell Jones interviened :

‘Don’t touch him! Man not drunk; man got gras.’ (grace)

Although the colliery was quickly back into production the Chester Chronicle ( 22 December 1837 ) tells us that a disagreement between the proprietors at that time resulted in them selling their interest to another concern . The disaster certainly left its scar on the community for generations to come.

NOTES

- This probably explains why 9 year old Henry Hughes was to later state that the possibility of death ‘never’ Enterd my mind’.

- Owen Jones came to Mold as proof-reader for the printer Evan Lloyd. He and his brother later set up their own press (H.&O.Jones), although he worked as Works Secretary to the Argoed Hall Colliery Company. He was ordained in June 1842 and appointed to Capel Bethesda in New Street, Mold. Not in the present building but one on the same site.

- These would have included the Bromfield and Broncoed collieries, Glanral’on Colliery, Mold Town Colliery-, Tyddyn Colliery and Rhydgaled Colliery, all within the Alun Valley. At Sychdyn you had the Soughton Colliery Company, while at Buckley there was another half dozen that included the Argoed Colliery and Buckley Colliery.

SOURCES

Manuscripts

Flintshire Record Office, D/DM/22; NT/1857.

North of England Institute of Mining & .Mechanical Engineers: T.E.Forster Collection, Vol. 15, pp.64,148; Watson Collection, Vol.68, p.40.

Newspapers and Journals

Caenarvon & Denbigh Herald (13 .May 1837).

Chester Chronicle ( 12,19,30 May 1837), (25 Octoberl839), (1 November 1839).

North Wales Chronicle (16,30 may 1837).

The Age (18 June 1837),(13 August 1837).

The Liverpool Mercury (19 May 1837).

The Mining Journal and Commercial Gazette (20,27 May 1837).

Y Bryntwn (1 Me he fir. 1837)

Articles and Printed Books

R.Church,

A.Hall &

J.Kanefsky, The History of the British Coal IndustryJ830-1913 : Victorian Pre-eminence, 3 ( Oxford 1986),

pp.310, 423, 556 572, 596.

E.Davies, Cofio Daniel Owen ( Y r Wyddgrug ),n.p.

J.E.Lloyd,

R.T.Jenkins,

W.Ll.Davies

(eds.) Dictionary of Welsh Biography down to J940 ( 1959), pp.499-500.

A. H.Dodd, ‘North Wales coal industry during the Industrial Revolution,” Archaelogia Cambrensis, (1929), pp.226-8.

” ” The Industrial Revolution in North Wales (Cardiff 1933), pp.315, 318-9, 322.

R.M.Evans, Children in the Mines, 1840-1842 (Cardiff 1972).

J.G.Jones, The Novelist from Mold (Mold 1976),p.ll.Jones, Hanes fanol a chywir o’r trychineb arswydus a gymerodd le yn Ngwaith Glo Plas-yr-Argoed

( Wyddgrug 1837).

R.Phillips, Y Dyfroedd Byw ( Yr Wyddgrug 1987 ), tt.26-7.

Winstanley, Children in the Mines : The Children’s Employment Commission of 1842 (Wigan 1998).

(ed.)

B. Wynne-Woodhouse, ‘Daniel Owen the novelist – family history’, He I Acliau , 12 (1984),pp. 11-17.

Copyright of articles

published in Ystrad Alun lies with the Mold Civic Society and individual contributors.

Contents and opinions expressed therein

remains the responsibility of individual authors.