By Derek Williams.

Until about 1750the mountains of north Wales were of little interest except to farmers using the hill pastures near their hafotai ‘summerhouses’ and few intrepid botanists. Before going up to Oxford University in 1682 Edward Lhuyd undertook a journey through the mountains of Merioneth with climbs of Aran Benllyn near Bala and Cadair Idris overlooking Dolgellau. He collected plants and recorded twenty six specimens, which had previously been unknown. Other students followed his lead and in the 1680s climbed Snowdon itself. They left unfavourable comments of the rain, mist, the steep rocky crags and in a Llanberis inn:

‘the bread being black, tough and thick oatmeal which we had not been accustomed to.’

It is not surprising that to most visitors, at that time, the mountains themselves held no appeal and this attitude survived until the mid-eighteenth century.

The breakthrough in attitude came about c. 1750 when mountain scenery began to be favorably regarded for their views, the associated waterfalls and the picturesque gorges and lakes. Visitors came to climb the most accessible mountains Snowdon, Cadair Idris and guides appeared in Llanberis, Capel Curig and, in Beddgelert, one guide advertised on his cottage ‘Guide lives here.’

One of the earliest to recognize and respond to this new trend was Richard Wilson who was born in 171 3/14 at Penegoes near Machynlleth where his father John Wilson, was vicar. The medieval church, with its cross-shaped plan and tower was rebuilt on the same site. The ‘new’ church has a wall tablet to Richard Wilson but the record of his birth in the parish has disappeared. In his early years the family moved to Mold where other members of the family lived This move necessitated the use of a horse-track route from Penegoes, which passed Cadair Idris, on their way through Dolgellau and Bala to Mold. Richard’s father was married to Alice Wynne of Leeswood Hall in 1709 but he retained the living at Penegoes. The family connection was even more pivotal when, in 171 3, George Wynne, brother of Alice, and then living in Leeswood Hall, benefited from the discovery of lead on land which he owned on Halkyn Mountain. With the money obtained from the mine George, who was Richard’s uncle, was able to finance a new mansion at Leeswood. It had the status symbols of a landscape garden, spectacular ‘White Gates’ and two lodges. A set of elaborate ‘Black Gates’ also survives and have been repositioned at the entranceway to The Tower, Mold . With the money George’s status increased; he became an M.P. and was knighted. A fine full-length portrait of him, dating to this period, hangs in The Tower and reflects his wealth and importance at this time (c. 1727) as an M.P. He left for London in 1729 and was able to finance Richard’s apprenticeship as a portrait painter in London. Initially he was apprenticed to Thomas Wright and took up residence in Convent Garden. There was a huge demand for portrait paintings and Wilson managed to paint a portrait of the Prince of Wales who later became George III. However, he was not as good as contemporary portrait painters such as Reynolds and Gainsborough. Wilson was mainly interested in landscape paintings with historical themes. At the age of thirty-six he went to Italy where he was impressed by the grand and heroic landscapes. He spent seven years in Italy, mainly in Rome, where he studied the ‘Old Masters.’ He also visited Venice and Naples that proved to be the happiest days of his life. In the classical landscapes he painted temples, villas, tombs, ruined aqueducts but always against an actual landscape He returned to London in 1756 and made his reputation on the Italian paintings. Most of these were painted in London and not based on ‘plein air’ method. It is probable that, although he is regarded as the ‘Father of English landscape painting’ very few of his paintings seem to have been painted outdoors.

Whilst in London living at varying addresses Lincoln’s Inn Fields, Marylebone, Great Portland Street he set up his first Exhibition in 1760 with his celebrated views of Italy — Niobe and View of Rome and became founder member of the newly-formed Royal Academy. He completed a large number of fine paintings but many were sold cheaply because they were unfashionable landscapes and Wilson was adversely criticised by Joshua Reynolds and other painters.

On his return to England in 1757 he had become aware that contemporary artists were drawing ‘real’ landscapes with wooded hills, grass-covered slopes and even crops and farming activities taking place. Although he lived in London he frequently visited his family in Mold because:

‘Wales afforded every requisite for a landscape painter’

He visited his mother in Mold and his cousin Catherine at Colomendy Hall near Loggerheards. His brother John was a collector of taxes in Mold and lived in Llanferes. On these visits he became familiar with the landscapes of north Wales and painted buildings and scenery. These paintings included the Dee Bridge at Holt, Caernarfon Castle and Conwy Castle, the hill-top ruin at Dinas Bran as well as waterfalls such as Pistyll Cain and mountains. The exact chronology of his journeys and paintings is not known apart from specific commissions. It was in the 1760s that Wilson began his main paintings in Wales and he was drawn to the mountains of Snowdonia. In 1764 he painted Caernarfon Castle and in the following year he completed his famous view of Snowdon from Nantlle which showed a strong link with his previous Italian landscapes This canvas so inspired the travel writer Thomas Pennant a few years later, that he actually made the effort to seek out the spot from which Wilson had made the painting. He described the viewpoint from:

‘two fine lakes called Llyniau Nantlie which from a handsome expanse with a very small distance between each. From hence is a noble view of Wyddfa [Snowdon] which terminates the view through Drws-y-Coed. It is from this spot that Mr Wilson has favoured us with a view as magnificent as it is faithftul.’

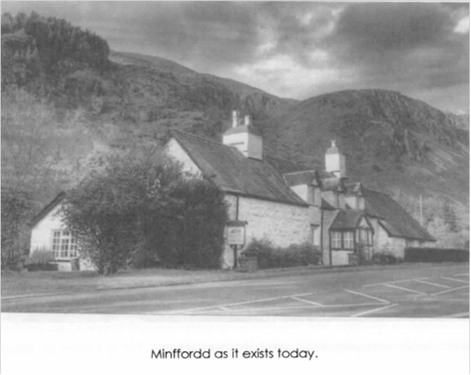

In his search for such ‘real landscape’ Wilson was also drawn to another Cadair Idris – which he knew from the times when he had crossed the Range on his visits from Penegoes to Mold On these visits he would have acquired knowledge of the geography of the huge Cadair Idris Range and the attractive scenery on the adjoining sides of the summit. He would have known about Craig Cau and the superb lake – Llyn y Cau – at its eastern foot. The road from Penegoes reached the small public house of Minffordd, which was referred to in a contemporary poem (1750) written to William Vaughan of Nannau, a mansion near Dolgellau. In the poem the poet showed his appreciation of the comforts of the inn at Minffordd because he : ‘ called readily at Minffordd’

Minffordd was situated between the medieval market towns of Dolgellau and Machynlleth and was built about 1700. It was a convenient overnight stop for farmers and drovers moving their cattle and sheep eastwards to England. It still retains its original structure with dormer windows set in the roof

Though not on a daily stagecoach route in Wilson’s day it was important for summer visitors in the late eighteenth century for travelling from Aberystwyth to Caernarfon, Machynlleth and Dolgellau It is often mentioned in the accounts of tourists of that time. It would have been a stopping place for travellers where horses could be changed before the steep ascent of the Tal-y-llyn pass. Under active landlords, such as Edward Jones, visitors were encouraged to cross Cadair Idris to Dolgellau and they often acted as guides to the summit. Visitors such as William Bingley undertaking a walking tour of north Wales kept a journal of their tour and gave a description of the inn at Minffordd – then called The Blue Lion Richard Wilson as a boy and young man would have passed, or perhaps even stayed at Minffordd, ascended the Tal-y-llyn pass and then crossed the mountain along the notorious Bwlch Coch pass to Dolgellau. The earliest written reference to Minffordd in 1750 gives us an optimistic view of the inn only a few years before Wilson’s time:

‘We called readily at Minffordd to drown doleful thoughts and from there over the severe Bwlch Goch; a road made at the beginning of the world for a sinner as punishment. Finally we arrived at Dolgellau and were released of our burdens.’

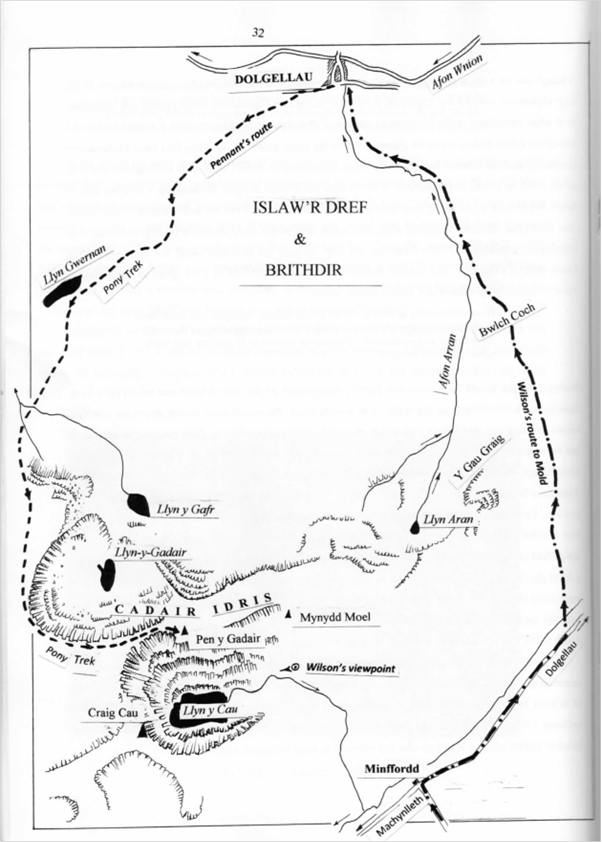

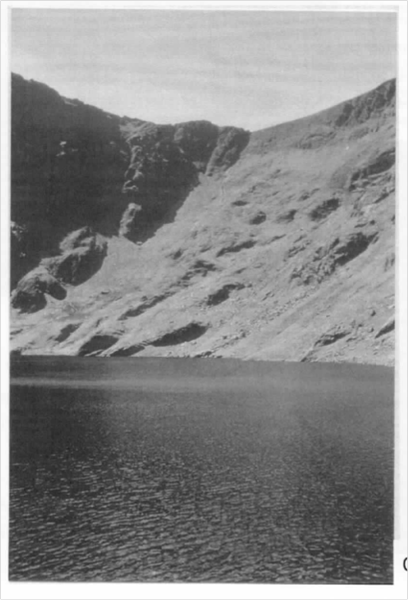

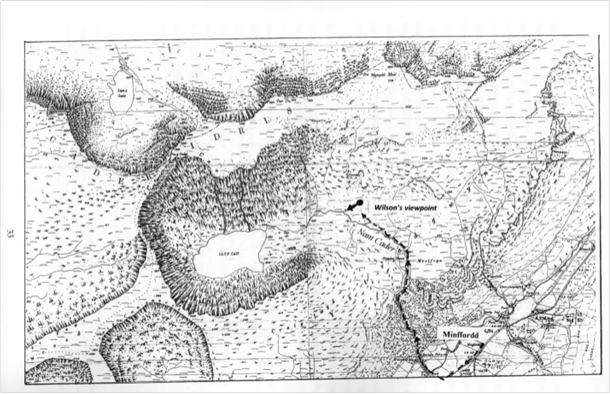

Richard Wilson would have made this journey many times on his way to Mold and would have been familiar with Minffordd and the ‘road’ over Bwlch Coch. He would have known about the stunning views of Craig Cau and Llyn y Cau which were only a mile above the inn. Both became the subject of his famous paintings from a viewpoint on the slopes of Mynydd Moel which was part of the Cadair Idris Range. Here he set up his easel about half a mile east of the lake and 500 feet above its surface. This gave him a full view of the lake as well as Craig Cau. the Tal-y-llyn Valley and, on the distant horizon, Cardigan Bay. As in his Italian paintings he included figures a man with a telescope and a few climbers. He exaggerated the height of Craig Cau above the lake to give a more balanced and simplified composition. To the modern observer the scene is a glaciated valley head (cwm) eroded by a local glacier surviving late in the Ice Age and eroding a rock-cut basin. The resulting deep ‘hole’ was later filled in – 12,000 years ago – to form a lake which is one of the finest glacial lakes in Wales. It was not until 1831 that the Glacial Theory was accepted in Britain and not until 1953 that the full depth 163 feet – of the lake was proved by plumb-line survey.

Shortly after the painting was completed, with at least two versions known, it attracted the attention of Thomas Pennant who lived in Downing Hall near Holywell and claimed to be a ‘kinsman’ of Wilson. He travelled extensively in north Wales and his Tours in Wales was published in three parts between 1 778 and 1 783 . He was a minor landowner, married to the sister of Sir Roger Mostyn who lived in nearby Mostyn Hall and who had substantial areas of land in north Wales.

Pennant was welcomed in the houses of most of the gentry of the region including Henry Vaughan of Hengwrt near Dolgellau and William Vaughan of Corsygedol. These squires commissioned landscape paintings of Snowdon and Craig Cau as well as other Wilson paintings. The strongest possibility is that he saw them at his brother-in-law’s house at Mostyn Hall. Apart from his visit to Nantlle Pennant also made a visit to Cadair Idris to see the spot where Wilson had painted Llyn y Cau

‘Cader Idris rises immediately above the town [Dolgellau] and is generally the object of the traveller’s attention. I skirted the mountain for about 2 miles, left on the right the small lake of Llyn Gwernan, and began the ascent along a narrow, steep horse- way into Llanfihangel-y-Pennant, perhaps the highest road in Britain, being a common passage for pack-horses. The hill slopes upwards to Pen-y-Gadair but the day proved so wet and misty that I lost the enjoyment of the great view from the summit. I at intervals perceive a stupendous precipice on one side where the hill recedes inwards forming a theatre with a lake at the bottom. On the other side I saw Craig Cau, a great rock with a lake beneath, possibly the crater of an ancient volcano. This so excellently drawn by the admirable pencil of my kinsman, Mr Wilson, that I shall not attempt the description. The ingenious Mr Meredith Hughes of Bala assures me that Pen-y- Gadair is 950 yards higher than the green at Dolgellau.’

This account shows that Pennant, travelling as usual on horse or pony, followed the conventional and easiest route to the top of Cadair Idris. He turned off at the summit of the pass and shortly afterwards saw on his left the ‘theatre’ which contained Llyn y Gadair and is reference

to the Greek and Roman man-made theatre. The path is still marked on the O.S. maps as ‘Pony Path’ leading to the summit from where he saw Llyn y Cau. as drawn by Wilson. His comment on ‘the admirable pencil of my kinsman, Mr Wilson,’ is a reference to the artist’s paint brush.

The height of the mountain was underestimated and was not corrected until nearly a hundred years later when the 0. S. maps showed it s 2927 feet

[ c.975yards ] above sea level.

By reaching the summit Pennant must have had the great satisfaction of seeing the exact spot at which Wilson had made his painting of Craig Cau. Having seen the painting at Mostyn Hall he satisfied his curiosity some years later (1784) got his illustrator, Moses Griffiths, to paint a replica in watercolour of the same scene. Wilson’s canvas was exhibited at the Royal Academy of Art in 1774 and an engraving of it made it a very popular and successful painting. It is also possible that Pennant had seen the painting at Corsygedol where he ‘was entertained by the late William Vaughan for some days in the style of an ancient baron.’

Wilson continued in the 1770s to paint scenes in north Wales including a valuable commission from Sir Watkin Williams Wynne who was the largest landowner in north Wales and had a mansion at Wynnstay, Ruabon, and his favorite house, Llangedwen. The date of this commission for the two houses and their exhibition was 1771. It was also at this time that Wilson painted the waterfall of Pistyll Cain near Dolgellau which has striking similarities to the Wynnstay and Llangedwen paintings in the colours used, foliage, rocks and foreground. The Pistyll Cain painting shows that Wilson was prepared to visit places which were difficult to reach. Lying two miles northeast of Ganllwyd near Dolgellau the falls could only be reached by a difficult path following the Mawddach Gorge. As noted previously Pennant in 1781 followed Wilson by visiting the falls he described in his Tours in Wales. It is

‘a vast drop, bounded on one side by broken ledges of rocks, on the other by a lofty precipice with trees here and there growing out of its mural front. . . . oaks and birch from distinct little groves, and give it a sort of character distinct from other cataracts. After the water reaches the bottom of the deep concavity, it rushes into a narrow rock chasm, of very great depth over which is an admirable wooden Alpine bridge.’

The influence of Wilson and Pennant can be seen when the waterfall was visited by William Bingley ( on a walking tour in 1798 ) who was also greatly impressed by Pistyll Cain. He describes:

‘the narrow stream rushes down vast rocks, at least 150 feet high, whose horizontal strata run in irregular steps through its whole breadth and form a mural front. Immense fragments of broken rock lie at the foot of the cataract and an agreeable mixture of tints of dark oak and birch with the yellower and fading elm formed altogether a highly pleasing scene.’

The decade 1765-75 was the high point of Wilson’s career in Wales with paintings of Caernarfon and Conwy castles as well as medieval bridges at Dolgellau and especially Holt which he retained for his own collection

During his visits to Mold and Colomendy he completed paintings of the limestone hills around Loggerheads and the village and church at Northop. It was also during this period that Pennant began his tours in north Wales and his interest in the scenery and history of the area. He was active at the same time that Wilson was actively painting here – the 1 760s and 1 770s.Frequent visitors to Pennant’s modest estate at Downing were taken to places within easy range the Vale of Clwyd, Conwy Valley and Penmaenmawr. From an early age Pennant had visited relations at Dinas Mawddwy and by the 1770s was familiar with most of north Wales, including Montgomeryshire. He was interested in cartography and in the first volume of his ‘Tour’ included proposals for the publication of John Evans’ Map of the Six Counties of North Wales and ordered six copies, but had to wait nineteen years ( 1795 ) before the map was published! Evans. who lived near Llanymynech, made a fine sketch of the nearby waterfall – Pistyll Rhaeadr – which was based on the style of Richard Wilson. Pennant visited Pistyll Rhaeadr and during a severe storm found shelter at the vicarage of the Revd. William Worthington, who later on, provided Pennant with six pages of notes about the parish. Llanshaeadr-ym-Mochnant. This active seeking out of information was typical of Pennant’s methods which provided authority for his ‘Tour.’

Richard Wilson was fourteen years older than Pennant and by the late 1 770s was suffering from ill health which was mainly due to gout and arthritis and which restricted his travelling. This was a factor in causing his return from London to Colomendy Hall as a guest of his cousin, Catherine. He was also in financial difficulties because his paintings were no longer considered fashionable and he was painting with a limited palette. It was a precarious living especially for a landscape painter and financially his career had ended a failure. In his final years (1780-82) he enjoyed brief walks in the hills around Colomendy and painted views of the lead-mining workings in the neighborhood of Loggerheads and Maeshafn. as well as the limestone hills and the Alun Valley – the prominent limestone crags of Cefn Mawr and other areas within reach of Colomendy can be identified in these later sketches and paintings. He died in 1782 and was buried just outside the walls of the parish church at Mold. His paintings of landscapes in Italy and north Wales were admired by John Constable who regarded him as the founder of the British School of Landscape Painting. According to Constable they were.

` Truly original because he showed the world what existed in Nature, but which had never been seen before’

William Bingley, while still an undergraduate studying theology at Cambridge, set out on a walking tour of north Wales in the summer of 1798. His intention was to follow in the footsteps of Thomas Pennant with the purpose of visiting all the places mentioned in Pennant’s Tours in Wales, published fifteen years earlier. He was using John Evans’ Map of the Six Counties of North Wales’ ( 1795 ) which ‘contains by far the fewest errors of any that has yet been published and now selling at the enormous price of one guinea!’

Having reached Minffordd, travelling along the new Turnpike Trust from Dolgellau to Machynlleth, he reached the Minffordd Inn, which had been renamed the Blue Lion, to spend the night before climbing Cadair Idris. He was disappointed with the food on offer at the public house which was restricted to bread and butter but there was plenty of fresh ale brewing in a tub. The landlord of the pub, Edward Jones, was a mountain guide as well as a schoolmaster and gravestone cutter. After breakfast the skies were still cloudy when Bingley and Jones set off at 9. am. They climbed the footpath along the sides of Nant-y-Gadair behind the inn and quickly reached the deep hollow of Craig Cau which had been painted by Wilson but not referred to by Bingley. Following the narrow ridge to the south of Llyn-y-Cau they reached the summit of Craig Cau and then the top of Cadair Idris which. ‘like Snowdon is conical and covered with loose stones. ‘ The spectacular views eastwards included Bala Lake and the Berwyn Range; southwards he had a view of Pumlumon and to the west he could see the whole curve of Cardigan Bay, from Pembrokshire to the Llyn Peninsula. Bingley then followed the ridge eastwards to Mynydd Moel with the ‘path sufficiently sloping to allow a person to ride even to the summit. A gentleman seated on a little Welsh pony had done that a few days before I was here. ‘ Bingley then descended the steep crags of Cwm-rhwyddfor, probably using a grass covered gully to avoid the rock faces and screes to reach the Machynlleth Road just up the valley from the Blue Bell. He spent another night at the inn where : ‘the bed I slept in was not a very bad one,’ and he dutifully recorded the bill for 5..Os ( now 25p ) which he considered ‘cheap living at this cottage.’

Two dinners (NB bread and butter 1 s Od

Two dinners (NB bread and butter 1 s Od

Tea., supper and breakfast 1 s Od

Ale 2s 6d

5s Od

The following day Bingley continued in the rain, along the road to Machynlleth which he considered ‘level and good’ with regular milestones along the new Turnpike.’

Minffordd ‘roadside’ is on the road from Dolgellau to Machynlleth. It lies in a crucial position at the foot of Tal-y-llyn Pass and near the shores of Tal-y-llyn Lake. Built of large local boulders littered at the foot of Cadair Idris, it consisted of two main rooms with fireplaces at each gable-end and a staircase to three bedrooms on the half-story above, each lit with a dormer window.

The thick roof timbers and beamed eighteenth century ceilings are still intact. The two broad chimney stacks at each end reveal the shape and size of the original inn. This is the building that would have been familiar to Richard Wilson when he passed and probably stayed on his long northwards journey. Its main function was as a drovers’ resting place when cattle and sheep were driven from Dolgellau, and areas to the north, and herded overnight in the 33 acres of pasture around the inn. The following day the drovers and herdsmen continued their long journey to Machynlleth and onto Smithfield in London.

The road from Dolgellau to Tywyn which passes its front door was improved by the Turnpike Trusts in 1777 and then the tourists came by summer stagecoaches on their way to Snowdonia. This was the time Richard Wilson knew the inn and its popularity and ambiance may explain why the artist chose his viewpoint and the painting of Llyn-y-Cau only a short distance north of Minffordd.

.

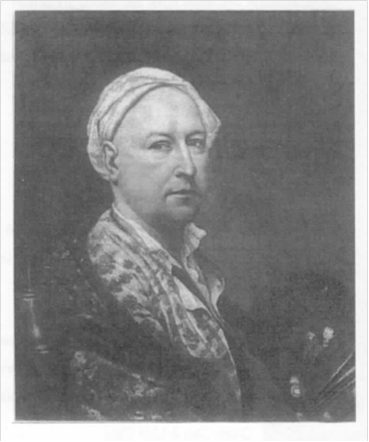

self- portrait at the Diploma Gallery, Royal Academy; Richard Wilson RA ( 1714-82 ) Father of British Landscape Painting born Penegoes (Monts), buried Mold (Flints).

.

Copyright of articles

published in Ystrad Alun lies with the Mold Civic Society and individual contributors.

Contents and opinions expressed therein

remains the responsibility of individual authors.