by Diane J P Johnson

As you leave Mold on the A541 towards Denbigh, just on the edge of the town is a modern chemical factory. However, the industrial history of this site goes back over 200 years, to the last decade of the eighteenth century when the Mold Cotton Mill was established there.

This was a boom time for the cotton industry in this country due to the huge technological advances that had been made in the textile industry in the latter half of the eighteenth century, bringing it from a domestic, cottage-based industry to a factory system.

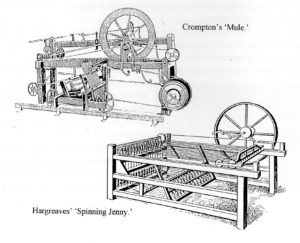

The innovations of this period included in the 1760’s Hargreaves Spinning Jenny, followed by Arkwright’s Water Frame for roller spinning, (which led to the establishment of the first spinning mill at Cromford, Derbyshire) and finally by Crompton’s Mule that combined the principles of the previous inventions.

As a result of these early small mills being water-powered, they had to be situated in rural areas where a plentiful supply of water could be obtained along with cheap labour, especially of women and children.

This could explain why in the 1770’s, James Smalley, an associate of Arkwright,s, came to the Greenfield Valley at Holywell and set up a cotton mill there. He may also have been influenced by the social unrest that was present in Lancashire at this time due to the fear of mechanisation. As this enterprise at Holywell proved successful, other mills were built and by 1790 there were three operating in the Greenfield Valley. This success could explain why other cotton manufacturers began looking to North Wales as a suitable location for their own businesses.

Another economic factor was the proximity by sea to Liverpool. This was an expanding port at this time with trading links to Africa and the Americas. In 1757, the first-ever cotton auction was held there, and from then on the volume of cotton imports steadily increased until it became the main importing centre of the country.

Cotton could easily be brought to the ports along the North Wales coast after a 2-3 hour voyage by barge or lighter. This would prove to be cheaper and more convenient than using road transport. For example, it would be possible to move cotton from Connah’s Quay, up Golflyn Lane to Northop and then on to Mold. Another possible route was from Bagillt, which had a history of being a depot for passengers and goods traffic with Liverpool from the 18th century, to Mold.

These might be some of the factors influencing the foundation of the cotton mill at Mold by Lancashire cotton entrepreneurs. Allied to this was the willingness of Welsh landowners to offer likely sites for industrial concerns.

An industrial opportunity at Mold was advertised in 1789 in the Manchester Chronicle, when an “overshot Water Stream, upon the River Allen, above Mold”, which had powered a very large water-wheel, was put up for sale. This may be the very area where the cotton mill was later built.

A description of the Rhyd-y-goleu area for this time can be found in a survey that was carried out for the then Lord of Mold, Thomas Swymmer Champneys, in 1791, regarding his estate. This was carried out by a London surveyor, a Mr Mather.

“R hydgolley Mill now in the occupation of Robert Griffith tenant at will, consisting of an Overshot Water Corn Mill on an old and bad construction with two water wheels driving separately two pairs of stones. The Mill House (part stone, part brick and slated), a small dwelling house adjoining a detached Wash house and stable (stone and thatched), the whole much out of repair”.

Another piece of the jigsaw can be found in this survey when it is stated,

“Farm and Water Corn Mill now in the Occupation of the Undermentioned persons Tenants at Will but agreed to be let on Lease for [?] Years at £120 per annum to Peter Atherton Esq., who is now constructing a Capital Cotton Mill and making the other Necessary Buildings for a Cotton Manufactory thereon. The Lease contains Covenants greatly in favour of the Lessor”.

Another reference mentions that Mr Atherton had a partner in this enterprise of building this mill between 1791-2, a Mr Hodgson from Uttoxeter. The cost was £20,000.

To compensate for the fluctuations in the flow of the Alyn and to allow the water-wheel to operate all year round, a reservoir 5-6 acres in size (Factory Pool) was constructed in the field opposite along with a connecting channel or “Force” (a lead-miners term). This was of a depth of nine feet, conducting the water with a considerable fall to the water-wheels. The remains of these earthworks can still be seen today as well as the keystone of the culvert taking the water beneath the main road. This is dated 1792.

The building itself was an impressive edifice of five stories and was so described as a “handsome and stupendous cotton factory, close to the town….., lighted by 220 windows; and is a useful neighbour to Mold as it employs a great number of the poor” (Pugh’s ‘Cambria Depicta’1807/1814). However, not everyone was so impressed by its presence, as in 1822, John Humphreys Parry of Mold, states the manufactory, “is a handsome building of the sort, and forms a conspicuous object in the vale, although the admirers of rural scenery may not be disposed to consider it as any accession to its beauty”!! Unfortunately, no contemporary image of the building remains other than that on a creamware jug, now in the National Museums & Galleries on Merseyside.

The ownership of the mill becomes very confused for the next few decades, as partnerships seem to be broken up and reformed with new names becoming involved, such as Bateman, Knight & Inman. These seem mainly to come from the Lancashire or Manchester areas.

In 1800, the mill was advertised in the ‘Manchester Mercury’ for sale by Messrs. Hodson (Hodgson?) & Leigh, cotton spinners of Manchester and Stockport.

Then it was put up for sale in September as Lot 75 in

‘A Particular and Conditions of Sale of The Manor of Mold etc, at the Griffin Inn in Mold, on the 3rd day of September 1801. It was described as:

“Cotton Mill in township of Gwernaffield. In holding of Robt Hodgson Esq & Partners, under 99 year lease, commencing 30 Nov 1791, and 12 May 1792 at the clear rent of £115 6s 0d with a covenant to erect a corn-mill at the end of the term, or pay to lessor £400”

(This would appear to have been bought by a Mr Calveley who may have been an Enclosure Commissioner.)

After the Lordship of Mold was sold to Sir Thomas Mostyn in 1805, an Indenture of 1808 mentions that the estate included, “All the messuage, tenement, Cotton Mill & buildings”. However, in 1815, Sir Thomas Mostyn sold and conveyed to James Knight Esq. (or to his brother, Samuel), the Cotton Mill, buildings and land. Also described were a weir on the River Alyn, land called the ‘Pool Field’, the Tail Race to the river and the Canal from the Mill pool to the Mill.

After the Lordship of Mold was sold to Sir Thomas Mostyn in 1805, an Indenture of 1808 mentions that the estate included, “All the messuage, tenement, Cotton Mill & buildings”. However, in 1815, Sir Thomas Mostyn sold and conveyed to James Knight Esq. (or to his brother, Samuel), the Cotton Mill, buildings and land. Also described were a weir on the River Alyn, land called the ‘Pool Field’, the Tail Race to the river and the Canal from the Mill pool to the Mill.

Artist’s impression of the Mold Cotton Mill. 1792

based upon a commemorative jug dated 1792, now at the Liverpool Museum [ F.R.O., Photo 40/301.]

and engraving of Greenfield’s cotton mills in 1796 [ T. Pennant, A History of the Parishes ofWhitford

and Holywell, plate XIX.]

Samuel and James Knight were from Manchester & were cotton entrepreneurs and speculators. They obviously made a success of the mill as they were able to acquire around this time the Rhual Estate from the Griffiths.

The Rhual estate had come up for sale due the death at the Battle of Waterloo of Major Edwin Griffith, the owner. His four sisters inherited it and as none were in a position to take on the great cost of repair and maintenance it was put up for sale and was sold to the Knights for £24,500. So they had in reality become local gentry themselves.

The Knights were also prominent in the community as bankers as well as proprietors of the mill. This was quite a common occurrence at this time and in Pigot’s Directory of 1828-9, “a cotton spinning manufactory belonging to Samuel & James Knight” is mentioned along with the entry stating, “Knight, Samuel & James, Bankers, drawing on Whitmore, Wells & Co. & Jones, Lloyd & Co. London.” However, by 1835, although the mill is described as being a “flourishing establishment” there is no mention of the Knights as bankers. We get an insight into this state of affairs from an entry in the Chester Chronicle of 31st August 1832, where an action concerning the recovery of certain deeds and documents from the Knights in relation to their bankruptcy of Dec. 1831 is mentioned. Apparently they had debts of £60,000. In the September of that year, when their credit had contracted due to the world slump of the cotton trade, ‘they had become embarrassed’ and made a formal statement of their affairs. One of them had then withdrawn his capital from a concern at Manchester and in ‘every way had endeavoured to meet their impending difficulties’. Hence they lost control of the cotton company and it was probably taken over by Messrs. Inman & Son at this time.

[ The Rhual estate was put on the market again and this time it was bought by Sir Alured Clarke who then handed it over to his niece, Mrs Henrietta Maria Philips who had been one of the sisters of the owner , Edwin Griffith].

Over the course of the first half of the 19th century, the cotton industry as a whole suffered from periods of prosperity and slump. This can be seen in the fortunes of the Mold Cotton Twist Company as it was now called.

The mill was built at a time of prosperity for the cotton industry and for the next twenty or so years that continued to be the case. It is even stated in one reference that by 1812 it was lit by coal-gas – a great innovation for that time, indicating the progressive nature of the management. By 1822, in the region of 300 people were employed and the mill was extended in 1825. Such was the expectation of future prosperity, but it did not last and by 1833 the mill was at a standstill. Trade did improve and by 1836, 236 hands were employed and by 1838, some 60 extra had been taken on.

This may be the time at which the owners began to install steam engines to supplement their water-power. Steam engines had been introduced into factories from the beginning of the 19th century and in Mold’s case, any development in water-power would have meant vast expense and practical difficulty and possibly the maximum of service had already been obtained from local resources. So it would have made economical sense to use this technology. As there was a ready supply of coal from collieries adjacent to the site of the mill, use of steam power would have made sense. One of these collieries, the Bedford, abutted the land occupied by the mill and apparently the factory was supplied with coal from the Soughton Mountain Colliery as well. However, certainly by the mid-30’s, under the ownership of the Inmans, thirty power looms had been installed and a steam engine was brought in at this time and a second followed soon after, giving the mill a total capacity of 112 horse-power.

The installation of these looms meant weaving as well as spinning was being undertaken on the site and this could account for the increase in employees. These new looms were worked by a staff of fourteen women under the supervision of two male weavers from Manchester. The Mold factory had long sent its cotton waste to Manchester but it was now able to send bales of stout calicoes, known as ‘domestics’ as well.

During the 40’s the mill was in operation as it is mentioned as a going concern in both the 1840 and 1844 Pigot’s Directories, but in 1850 there is no reference to cotton at all. By this time the mills at Holywell had ceased operation, partly because they had never adapted to weaving. The 1841 census shows that of the 246 cotton operatives in Flintshire, Holywell only accounted for 14 of them. However, soon Mold was in a similar position as during the 1850’s there are several accounts from visitors to the town talking about the mill, saying “an extensive cotton mill …..which is not at work”(1850), “mill….brought to a stand, much to the injury of the town”(1851) and “mill….is now unoccupied”(1854).

During the 40’s the mill was in operation as it is mentioned as a going concern in both the 1840 and 1844 Pigot’s Directories, but in 1850 there is no reference to cotton at all. By this time the mills at Holywell had ceased operation, partly because they had never adapted to weaving. The 1841 census shows that of the 246 cotton operatives in Flintshire, Holywell only accounted for 14 of them. However, soon Mold was in a similar position as during the 1850’s there are several accounts from visitors to the town talking about the mill, saying “an extensive cotton mill …..which is not at work”(1850), “mill….brought to a stand, much to the injury of the town”(1851) and “mill….is now unoccupied”(1854).

The industry somehow picked up again and in the 1861 Census, the numbers being employed had risen to 171, but again the mill was only operating as a spinning establishment.

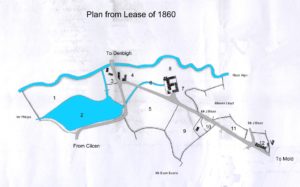

During all this upheaval the ownership changed several times and the Tithe Map of 1839 records Thomas Trueman as landowner, living in a house close to the mill and a Mr Knowles living at the Manager’s House. Another owner was a William Craig, cotton spinner, and in a lease of 8th October 1860 he cedes over all the properties to a Mr Frederick Septimus Bateson of Lancaster, also a cotton spinner, for a rent of £650 per annum for 21 years. This lease gives us some indication of what was contained and owned by the mill :-

“Mold Cotton Mill together with Engine House, mechanics shop and other buildings.

Reservoir of water and other appurtenances thereto adjoining or belonging.

All the Messuage or Dwelling House with the stable, cowhouses, outbuildings, gardens and appurtenances thereto belonging and also the 34 cottages, buildings and premises as delineated on the plan.

Together with all the outhouses, edifices, buildings, sluice ways, water, water-courses, run of water and all water and other privileges.

Mr Bateson is to amend, maintain, support, cleanse and keep all in repair. He is to oil the machinery with best sperm oil and to paint all wood and iron, inside and outside, every five years.”

It then goes on to describe the machinery within the mill :-

“Iron Water Wheel, 28 feet by 20 feet, with iron buckets, Pentrough cast iron shaft and ashlar foundations.

One condensing steam engine of 30 horse-power.

One condensing steam engine of 16 horse-power.

Three boilers with an aggregate of 140(hp?) with gauges, valves, fixings and connecting pipes to steam engines all complete.” One of these boilers is described as being “28 feet long, 8 feet in diameter with two long flues through”. The others are both “multi-tubular with flues through” and are 24 feet long, 6 feet, 6 inches in diameter and 16 feet long, 6 feet in diameter in diameter respectively.

“A cart weighing machine and all the shafting, gearing, fixings, bearings or pedestals.

Steam and gas pipes and all the taps, valves, burners and fixings in and about the Mill and premises.

Gasometer, two retorts, purifiers, hydrometer and fixings.

Two hoists with ropes and fixings.

Information for the above plan

No Names of Field Acreage No Names of Field Acreage

1. Coitia Uyn 6 1 20 8. Cotton Mill Meadow 8 1 15

2. Mill Pool 5 0 0 9. Field before the House 4 0 35

3. Houses & 1 2 8 10. Dwelling House & Garden 0 2 38

4. Garden 1 2 8 11. Erw Maes y Dre 1 0 34

4. Field by Mill Race 5 1 13 12. Houses & Gardens 0 3 5

5. Mill, Yard,

6. Buildings etc 0 3 30 34 1 38

From this description we can deduce that it must have been a very substantial undertaking and its presence must have made a big impact on Mold both on the physical landscape and on the social fabric of the town.

As early as 1791, in the survey undertaken for the Lord of Mold, Mr Mather in his description of the lands by the Bailey Hill, comments

“leases granted on Lives or long Terms of Years of the Ground opposite thereto adjoining the Road to Flint and of the Ground in New Street(?). Tenants would be found who would Erect in the stead of the Shabby Cottages therein, Neat and Uniform Houses to be occupied by the Manufacturers and such as will be concerned or employed in the Cotton Manufactory establishing there.”

Hence the prospect of this industry coming to Mold meant that more houses would have to be built to accommodate the incoming workers. The area of Maes-y-Dre saw considerable building development during the early 19th century with many Lancastrians settling there. In the 1841 Census, most of the cotton operatives in Mold seem to be living in the area close to the factory, namely Maes-y-Dre, Milford Street and Henffordd as well as in the Rhyd-y Goley area. This census shows that the majority of the employees were young women, girls, boys, with just a few older men and women giving their occupation as cotton spinners. The young women seem to be mainly late teens of early twenties, with some of the children being as young as nine or ten like Catherine Thomas, aged nine of Henffordd and John Jenkins, also aged nine, also of Henffordd. You can see whole families being involved in this industry so any downturn in the business must have a profound effect on whole communities. Sometimes the father or older male members were involved in other occupations mainly lead-mining, working in collieries or as agricultural labourers. Sometimes in one household there was more than one surname mentioned, mainly of young people, indicating that they could be from outlying parts and were lodging with these families.

We get some idea of the wages of the employees from the records of the Mold Select Vestry for the early 1830’s showing that many women worked in the mill for 5s per week and a boy of 13, for 2s a week. Although the wages were low they were probably average for the times.

At the beginning of the 19th century, legislation was introduced regarding the running of factories and in the report of the Flintshire Quarter Sessions, held on 14th July 1803, it was ordered,

“That the following magistrates and clergymen be appointed visitors of Cotton Mills in this county pursuant to an Act of Parliament lately passed for that purpose”. Of the Mills in Mold, Thomas Griffith (Rhual?), the Reverend Richard Williams, Clerk and the Reverend Howard, Clerk were appointed.

It would appear that the factory was occasionally visited by the Factory Inspector and it seems to have complied with the Factory Acts to his satisfaction.

Another piece of legislation the owners of the Mill had to adhere to was the sending of the infant workforce to school for part of the day. As it proved to be cheaper to run the school on the factory premises, this was done at Mold. Thus a school was opened in 1834. The Commissioners of Inquiry into the State of Education in Wales sent an Inspector to report on the school in 1847, and this is the summary of his report :-

“A school for boys and girls, taught together, by a master, in a room in the factory. No of scholars-30. Subjects taught – the Bible, Church Catechism and reading. Master’s salary, £20.

I examined this school, March 2nd. I arrived an hour after the time when the school professed to assemble, and therefore at a time when all should have been employed with their studies; but I found only 3 children assembled. At length 19 were summoned, among whom I found 2 who could read a verse of the Bible, and answer some Scripture questions. They receive no instruction in reading, writing arithmetic, or any higher subject. The rest were ignorant of everything secular and Scriptural; they were for the most part, unable to understand the most familiar phrases in English; their manners were rough and uncouth, their persons were extremely dirty, and their clothes tattered and threadbare.

The master was formerly a carrier. He has had no kind of education. He appears to have received his present appointment rather out of charity, in consequence of loss of a leg, than from any other consideration.

The school-room would only accommodate 26 children. It was intensely hot and filthy in the extreme.”

It is speculated that this one-legged schoolmaster is the basis of Daniel Owen’s character of a similar occupation in his novel ‘Rhys Lewis’. Daniel Owen was born in Maes-y-Dre and lived all his youth there at this time, so this factory school-master must have been a familiar figure in the streets when he was ten or eleven. Although he never worked at the mill, he must have known many local neighbouring children who did.

It would appear that many of the workers attended the Weslayan chapel, Pendref which flourished at this time.

One factor which must have hindered the long-term success of the mill as the century moved on was its distance from the cotton exchanges and markets of Manchester and from the other industrial processes involved in the finish of the cloth eg, dyeing etc, in comparison with those more favourably placed in Lancashire. Initially local communication was adequate and ‘although the expense of carriage of the raw and manufactured material was great, still the concern was worked at a profit’, ( Rambles around Mold, 1869). In pursuit of better communications James Knight in 1825 had agitated for a bridge across the Dee at King’s Ferry (now Queensferry), presumably to link Flintshire with Manchester by the proposed ‘Manchester and Dee Ship Canal’. This was a scheme promoted by a number of Manchester industrialists who wished to facilitate the increasing traffic between Lancashire and the sea and vice versa. The canal was to extend from Dawpool – 4 miles west of Parkgate on the Wirral Peninsula, across the Peninsula to Helsby and Preston Brook then to follow the line of the Bridgewater Canal to Manchester. The engineer was to be Robert Stevenson and the cost was thought to be in the region of £1m. However, it never happened as the Parliamentary Bill was dismissed on a technicality.

Another important development in transport was also making its mark in the first few decades of the 19th century and that was the coming of the railways. Again the cotton mill owners in Mold were at the forefront of trying to establish some form of rail link to reinforce the road system by supporting the North Staffordshire Railway Bill in 1837 but they had to wait until 1849 before a line was opened between Mold and Chester.

However, the history of the mill came to an abrupt end on the morning of 8th November 1866, when, according to the Flintshire Observer , 16th November, 1866,

“About half-past four o’clock on Thursday morning week, the usual quietude of the town of Mold was disturbed by the cries of ‘Fire’. There stood about half a mile from the town, in Maes-y-Dre, a large eight-storied cotton mill, built of brick in the from of a square with outbuildings and offices contiguous. This building which was one of the largest in the district, was early on Thursday morning entirely destroyed, and its valuable contents, consisting of a large stock of raw material and a large quantity of new machinery, were consumed. The premises were in the occupation of Mr F.S. Bateson, a gentleman who is well known in Liverpool. There was a strong wind blowing at the time and the efforts used to prevent the spread of the flames were ineffectual. Immediately after the discovery of the fire, which was in the card room, it spread with such alarming rapidity that every part of the building was enveloped in one common sheet of flame. From the first there appeared no hope of saving the premises, and the only piece of machinery that was rescued was a carding machine. Fortunately a large amount of cotton which had only arrived at the station that day had not been dispatched to the mill, otherwise the loss would have been more serious. There is no clue to the origin of the fire. The loss is estimated at £20,000- £25,000, a considerable portion, if not the whole, being covered by insurance. The calamity has cast a gloom over the town, and will throw out of employment upwards of 200 people.”

This optimistic view of the insurance cover does not seem to be borne out as another commentator , Charles Leslie in ‘Rambles around Mold’(1869) says that this sum fell far short of its real worth and as the cotton market was in a state of slump due to the American cotton famine due to the American Civil War, there was no inducement to build it up again. When he was writing some three after the fire, the site was still in a state of dereliction and most of the poor families that had been ruined by it , had sought other “homes to labour in for their subsistence”. This is confirmed by an entry in the Welsh publication (Cymru) which states that the catastrophe forced ‘rhaidegau’ (some tens) of members to move away to Manchester, Rochdale and Pendleton.

The lease between Bateson and Craig was cancelled on the 26th December 1866.

Thus the history of Mold’s first manufacturing industry came to end. It was typical of its time in that it was supported by a variety of industrialists, mainly from outside the area, who wished to gain a part of the huge financial rewards that could be obtained from speculating in new industrial ventures and in bringing in new technologies. Some were successful, some were not. However, they made a large contribution to the development of Mold and that legacy is still with us today.

PRIMARY SOURCES

Prof. W.G.V. Balchin ‘Living History of Britain’

- Davies & C .J. Williams ‘The Greenfield Valley’

- J. Williams ‘Industry in Clwyd’

K.D.Davies ‘Manufacturing Industries of the Greenfield Valley’ (Flintshire Record Office)

- J. Foulkes Flints. Hist. Soc. Jnl. Vol 21

- H. Dodd ‘The Industrial Revolution in North Wales’

Maj. B. Heaton ‘A Short History of Rhual’

Nansi M. G. Cubley ‘Made in Mold’ (Flintshire Record Office)

Leslie ‘Rambles Round Mold’

Flintshire Record Office Lease between Craig & Bateson (D/KK/960)

Flintshire Record Office Survey & Value of Thos. Swymmer Champneys (D/KK/267)

Flintshire Record Office Particulars of Sale D/M/3307

- Evans ‘History of Mold’ (Flintshire Record Office)

SECONDARY SOURCES

National Library of Wales N. L. W., MS.1755A

National Library of Wales N. L. W., Bettisfield.1686

Copyright of articles

published in Ystrad Alun lies with the Mold Civic Society and individual contributors.

Contents and opinions expressed therein

remains the responsibility of individual authors.