Mervyn E. Foulkes.

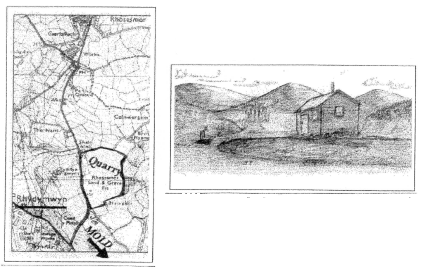

After a couple of years delivering groceries it came time for me to leave school for full time employment. My elder brother put me in contact with a Mr. Sid Edwards, foreman of the Rhosesmor Sand & Grave! Company whose quarry was situated at the bottom of the hill before you reach Rhosesmor from the direction of Mold. The owner was Mr. Ted Whitley of Whitley Bros, Wrexham, on land owned by the Davies-Ccokes of Gwysaney Hall. I saw the foreman in his home one evening, and alter answering some questions he put to me, was told that I could start work as soon as I liked. This I did by finishing school on a Friday and commencing work on the Sunday. The year was 1956 and I was fifteen years of age. For the first week the foreman gave me a lift in his car as the plant was shut down for maintenance during the firm’s annual holiday. His brother Walter Edwards and another Mold man, Arthur Crawford, were the plant’s maintenance engineers and they accompanied us. On arrival I was shown to the workmen’s cabin where 1 put my snappin bag on the table. It contained sandwiches in an OXO tin, an enamel brew tin with the lid as a cup, some tea, sugar and milk. Foreman Sid said, ‘Come with me’, and 1 duly followed. We walked back downhill from the plant for about four hundred yards, to a small farm run by a Mr. Jim Powell, and at the corner of the building was a pint of milk which I was to pick up every day during the shutdown for the foreman’s tea as the regular ‘Can Lad’ was on vacation with the rest of the workforce.

This task done on that first morning he then gave me a big shovel and took me to a huge pile of gravel spillage and told me that my job was to shift it by throwing it out to a position where it could be picked up by a mechanical shovel. 1 was left working all day at this pile which must have been accumulating for months! The plant’s principal purpose was to wash and separate sand and gravel which was dug out of the quarry. At the time that 1 started there was no electricity and everything was driven by two giant Blackstone Oil Engines which were started by compressed-air from a large air-receiver which was filled daily by the engine exhaust. These engines had a huge fly-wheel (approximately five feet in diameter) to which was attached a shaft onto which, in turn, was fixed a flat pulley. Thus the washing plant was driven by a series of pulleys and flat drive-belts. On average these belts were eight inches wide and there could be anything up to twenty-five feet between pulleys. On average these pulleys ranged from one to five feet in diameter, none of which was guarded, and when they were running could be very dangerous if you didn’t have your wits about you. Over the whole plant there must have been at least twenty pulleys, belts and drive-shafts all in motion at the same time, and we had to work amongst them. At the ‘hopper’ where the dump-trucks tipped into the plant you had to stand on a large grid at the bottom with a pick and a long poker to feed the sand and gravel through. This then fed into an open bucket-elevator which elevated it up about forty feet into a revolving-drum washer and through this into rotary screens that separated and graded the sand and gravel. The large stones were then fed through a crusher and crushed to suit the size required. A gain,, they went onto an elevator and into a repeat washing and screening plant before being put away in storage hoppers ready to be despatched to customers. For the washing of this aggregate the water was pumped up from Rhydywyn about two miles away, and as I write, I see this little pumphouse is still there. This was looked after by a chap called Noah Jones who started the oil engine-driven pump in the morning and made sure it ran all day. He also looked after the large lagoons into which the water returned from the plant (recycled) and the sand and silt settled out. Sometimes I was sent to help Noah to move big pipes and troughs to divert the water. I also stood in for him during his holidays or sickness. I have dwelt over the quarrying process and engineering involved to emphasize how labour-intensive and dangerous jobs were allowed to become before the days of the Health and Safety Act. We had no protective clothing and had to work in all weathers, and being high above the valley floor, we had to endure driving sleet and snow in the winter. Often, our only defence against the elements were a couple of worn out gabardine mackintoshes which you had perhaps received as cast-offs from an uncle or a neighbour.

As was the norm in many quarries half a century ago, there were no general facilities and our water for a brew was taken from a spring in a nearby wood. It was beautiful sweet water to drink. Having no hot water was particular)’ difficult because our hands were forever covered in oil, diesel and grease. For washing purposes we had to wholly rely upon a solitary cold water tap stuck on a piece of pipe that came out of a spoil bank opposite our cabin door. For toiletry we had to take a shovel with us behind a bank in a disused part of the quarry, scrape a hole in the sand and cover up whatever materialised afterwards. I should add that there was a chemical toilet at the offices for the four staff, one of which was a woman, a Mrs. Jones. Now let me introduce you to some of the characters I worked with. As you entered the offices we had Fred Parry, plant manager, and Cliff Tattum, wages,etc. Then there was Mrs. Jones, secretary, who dealt with invoices, etc., and a chap that I had worked closely with at the weighbridge, Dick Rogers. Dick farmed a smallholding on Halkyn Mountain and came to work in a old, white Austin Seven van. Whatever the weather he and his vehicle never failed to arrive. This can be put down to the fact that during inclement weather he would put two old fashioned milk churns in the back for ballast, and away he’d go! On numerous occasions I have seen traffic stuck on Rhosesmor Hill and Dick would weave passed them all, never stopping and never failing to reach the top. In those days remember, there was no salt to spread on the roads although we did supply Flintshire County Council with ‘pea gravel’ grit to spread on some surfaces. I believe the secret of Dick’s success was the van’s tyres. They were of a large diameter and very narrow so that they went straight through the snow to the road surface, and with his bit of ballast, he would always manage to get a better grip than his co-road-users.

Another incident that comes to mind involving Dick also took place when the snow was deeep and drifting. It was a bitterly cold day and no orders had been received. AH the drivers were huddled together in the weighbridge office which was hardly more than six feet square with a little desk like something out of a Charles Dickens’ novel. The heating came from a pot-bellied coke stove. Now try to imagine six drivers, Dick and myself crammed into this small space. The chattering sometimes drove Dick to despair as he was supposed to carry on regardless with his clerical work, answer customers and take orders over the phone. It was chaos, but Dick always had the solution. He would slip out to the chemical toilet, empty the contents onto a shovel, take it into the weighbridge and place the shovel on top of the stove until the ‘ingredients’ was boiling. Phew! You can imagine the stench – which never affected Dick – but it cleared his office for some considerable time!!

One year as Christmas neared. a workmate Richard Davies and myself went downhill during our dinner break to gather holly for those at the quarry who wanted some festive decorations. Having done this we distributed it out on the yard in front of the offices and thought no more of it. Later that afternoon there was a tap-tap on the weighbridge hatch and when Dick opened it there was the local landowner from Gwysaney. Squire Cooke, astride his big white horse, which incidentally, was up to its hocks in holly berries and leaves. The first thing that Dick did was to remove his hat (as this was still the done thing in the presence of gentry) and asked. ‘Can I help you Sir?’ To which the Squire replied, ‘I believe some of your men have been stealing some of my holly, and 1 want to speak to Mr. Parry about it.’ Dick responded by picking up the phone (the old wind-up type) and said, ‘Fred, Tom Mix is here to see you!’ Mr. Parry came out immediately and denied everything although it is more than likely that he had the largest share of all.

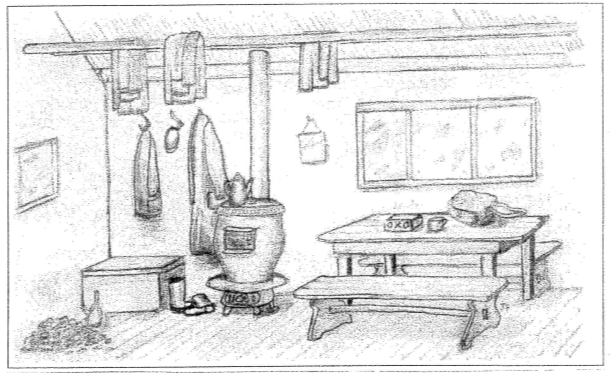

Charles Hubbard was the ‘Can Lad’ and general dog’s body. I think he was a great bloke and all the men thought the world of him. He was about thirty years old and living whith his mother when 1 started at the quarry, and it would be true to say. that he was a bit slow in his thinking. Our cabin, and ‘Charlie’s Domain.’ ( drawn by my brother John) looked like this :

It was a single storey building made of concrete blocks with an asbestos sheet roof, and as can be seen, a large pot-bellied coke stove towards the middle, with a four inch cast pipe through the roof for a chimney. Two one inch pipes were across the roof trusses for us to hang our wet clothes on. Around the circumference of the stove was a four inch ring on which stood our enamel tea cans to boil. In one comer was a pile of coal for the stove, while a wooden trestle table was provided for us to sit at to eat our snappin. There was no mains electricity, only that produced by a small oil engine-driven dynamo which sometimes generated – after dark – and lit a few bulbs around the plant, one of them being a solitary light in our cabin. It was Charlies duty to see that our water cans were boiling for our rest breaks. We had ten minutes for tea at 10.00am and half-an-hour at dinner time, and woe betide him if they were not on the boil when we came in because break times were strictly adheared to and a miscalculation on his part meant that you sometimes went without a brew. To be fair to Charlie, that didn’t happen often. Charlie had other chores to do around the site. He had to help out on the plant by carrying diesel for the Blackstone engines, oil and greasing the plant, and what we called ‘picking blacks’. This was done by standing by one of the conveyor belts for hours on end watching the washed gravel pass by and picking out the clay and ‘blacks’. The latter were small pieces of half-formed coal which played havock if incorporated in concrete. Once exposed to air they disintegrated and left unsightly holes on the surface of concrete or in the mortar of brickwork. ‘Blacks’ also renderred both sand and gravel useless to builders, so Charlie’s job, although boring, was an important one.

Although liked by everyone, his work as ‘Can Lad’, led in him being the butt of many jokes, some of which I can recollect. The first that comes to mind is when he was put under an upturned cylindrical gravel screen which was about six feet high and four feet in diameter. He looked like a caged animal and the men had fun pretending to feed him dandelions. However, when it came time for them to release him they were afraid of doing so because he was so mad with rage. Ultimately, the foreman’s brother came along and set him free, only to be hit with a beautiful uppercut that Mohamed Ali would have been proud of. It laid him out cold! When Charlie got annoyed with his workmates it was time to disappear. He would literally empty the cabin. We would be the first to leave, voluntarily and in a mad dash , often into the pouring rain with snatched snappin and drink in hand. Every piece of furniture, clothing, tea cans, and perhaps as much as half ton of coal, would be next; strewn around outside. This emptying of the cabin was a regular occurrence and probably happened once every fortnight. The irony of it was that when he had calmed down it was Charlie, and he alone, who had to put it all back again.

The worst culprits for starting him off were Cliff Tattum and one of the drivers. They had this worked down to an art. Having deliberately upset him they would quietly disappear, leaving the rest of us to to face his wrath. I remember very well being in the cabin one day whilst it was snowing heavily and blowing a gale. It was almost too cold to eat our sandwiches. Suddenly. Cliff Tattum burst in with about six snowballs on his arm, shouted. ‘Geronimo!’ And proceeded in belting Charlie with all six. Needless to say, the cabin was emptied of all its contents and we had to suffer an utterly miserable dinner break out in the biting wind. Cliff thought this hilarious and repeated the stunt on numerous other occasions when it snowed.

Another thing the men would do was pull Charlie’s leg about his widowed mother. They knew he cherished her so when he was mischievously told that Bob Jones, known as ‘Bob Maeshafn’, was trying to court her, to say that he did not relish the idea would be an understatement. Because of this he always kept a wary eye on Bob whenever he was around. Of course it all came to a head one day when Bob was having his usual fortywinks at lunch-time. The men were goading Charlie that the snoozing Bob had been out with his mother and was hoping to marry her, with its implication that he would soon calling him ‘Dad.’ [Of course none of this was true. Bob probably did not even know his mother.] Suddenly the signs were there. It was cabin-clearing time. Everyone trooped out in a disorderly manner, while at the same time, trying their best to gobble sandwiches and gulp a drink in the remaining allocated minutes. Everything, bar one item, found its way outside. Bob Maeshafn took no notice of the calamity and kept his chin on his chest as he always did at snap time. The final act from Charlie was to pick up the ‘set’ [a small hand-axe type tool used for cutting thin sheet steel] which we used for breaking up the large lumps of coal, and let fly with it across the cabin. It hit Bob just above his left eye splitting his eyebrow open. Blood spurted out leaving him almost unconscious, and after a rapid,crude first aid job [we only had plasters], he was dashed down to Mold Cottage Hospital where he had, I believe, three stitches put in his wound. Needless to say, BobMaeshafn’s name was never again mentioned in relation to Mrs. Hubbard.

Bob was a grand old bloke of about sixty-seven or eight at that time and as fit as a fiddle, always smiling, never ill and never failing to turn up for work. He had to ride a push-bike from Nercwys to Mold every day to catch our transport to the quarry. He worked five days a week, doing his shopping on a Saturday, when his favourite meal was a pork pie from Hulsons of Mold. This transport I mention was one of the delivery lorries with a small hut on the back which would seat about half a dozen men. In those days it was quite common to see workmen travelling to their place of employment in this manner, and on the occasional beautiful summer’s morning when we arrived early, we would continue to sit in this shelter listening to the birds singing in the peaceful quietness of the countryside; reluctant to get off to start work. The driver was usually David ‘Dixie’ Price who would be shouting from his cab until he was hoarse for us to get off. No one would take a blind bit of notice of him until he resorted to putting the lorry’s tipping mechanism into gear and proceede to tip the body up to such a stage that the hut and all of us men inside slid down the tipped-up body into a heap, amongst laughter and shouting. Of course, the driver would only let the body down when we promised to get ourselves and the hut off. Can you imagine a group of grown men on top of one another unable to move until Dixie let the body down. This hut would have to be manually lifted on and off for each journey If I worked on a weekend I had to use my bike to get there or cadge a lift, which reminds me, I was telling you about Bob.

His job was to look after the part of the plant that dealt with the fine ‘blacks’, the problem bits of coal previously mentioned. The finer element of this coal was floated off the sand and gravel with water which went over a fine mesh to trap the particles and Bob used a hand scraper to rake them off into a wheelbarrow to be taken away. In these ‘black’s you would also find bits of small sods and grass and a steady supply of worms which Bob used to keep for the birds, in particular, a blackbird that nested in the support girders of the plant. Bob had made it a habit of feeding this bird for a couple of years and it was very tame but in no way would it eat off his hand. I remember challenging him one day that I could get it eating out of my hand within a week. He laughed loudly and said it was impossible. Sure enough, 1 achieved my boast by starving it of worms for a few days when it had a nest full of young. Bob’s kindness had prevented it eating from his hand. As a reward for my ingenuity he gave me a sweet. Sad to say, we found this bird one morning dead in the washing water of the plant. Another of Bob’s tasks was to hourly clean the bottom of an elevator pit. This pit (and there were two of them) was a very dangerous place to be and I , as a young lad, had to be constantly watched by Bob during the first two or three occasions that I undertook the task. It was company policy that all hands had some degree of experience in the various aspects of work at the plant. The elevator pit was fifteen feet deep, six feet wide and twelve feet long. To gain access to it you had to climb down a home-made vertical ladder, at the bottom of which there was an open-bucket elevator for raising the sand and gravel into the washer screens. It was the operator’s job to squeeze down to the pit and shovel the spillage back into the buckets. You had very little room to manoeuvre, your knuckles and the back of your hands were forever cut and bleeding as a result of being knocked and scraped on the back wall as you used the shovel. Dangerous work at the best of times, especially since one wore an old mackintosh which could have been caught or snagged in the buckets at any time, dragging its wearer into the machinery with dire consequence. If that was not enough, water was continually streaming down on you off the plant like very heavy rain. If your employer forced you to work in such conditions today a heavy fine (or even imprisonment) would be imposed on him. 1 shudder to think of how we risked our lives in those days.

Jim Crawford was a small chap and brother of Arthur already mentioned. He came to work on a BSA ‘Bantam’ motorbike from as far as Meliden. One winter’s evening he’d had a great deal of trouble reaching home as the county was covered with about four inches of snow. On arrival at his village some snowballing children brought his attention to a power cable that the snow had brought down from overhead. Jim, afraid that the playing youngsters would be electrocuted rang the emergency number of M.A.N. W.E.B., who, after an hour and a half ‘s delay, arrived. Jim, frozen to the bone after standing for so long as guard over this cable, directed the engineer to where it lay, by now under the snow. The electric man took one look at it, scratched his head, picked it up and calmly tossed it to one side. Turning to Jim he said, ‘Thank you very much. It is not a problem sir. It has been dead for years. Good night!’

Another tale concerning Jim involves him poaching. There were literally hundreds of pheasants either near the quarry or in nearby woods. You may recall we had no official toilets and everyone had his own favourite spot. [The thinking behind this was that i f you trod on anything it was in all probability your own!] At Jim’s spot there was always a couple of pheasants strutting around at which he would take aim with a large stone and one time in ten would score a direct hit. Stuffing it down his overalls he would then take it down one of the elevator pits and pluck it ready for home, putting the feathers into the elevator to get rid of them. After a few years he moved to live within half a mile of the plant and quite by accident discovered another way of snatching birds. On his walk home up a lane or what we call ‘a sunken road’ (a lane with high banks on either side and hedged on top), he noticed that the farmer had put a one-and-a-half inch mesh wire netting along the base of the hedge. He also noticed that pheasants, in their eagerness to escape ran up the bank, poked their heads through the mesh and became trapped; like fish in a net. All Jim had to do was reach up, pull them out and quickly despatch them under his overall. I bet Jim’s family ate more pheasants than any of the local gentry. Jim was also very good at wine making, distilled from different plants he gathered in the fields and hedgerows. When the weather was particularly cold he would bring some to work to keep us warm and our spirits up! I remember, in particular, him giving a bottle to Ivor Glyn Jones who farmed Twmpath just outside Rhydymwyn and who supplemented his income by working at the quarry. Ivor liked the wine he had been given so much that every ten minutes or so he would disappear for a large swig. Consequently, by 11.30am he had to be taken home because he couldn’t stand up.

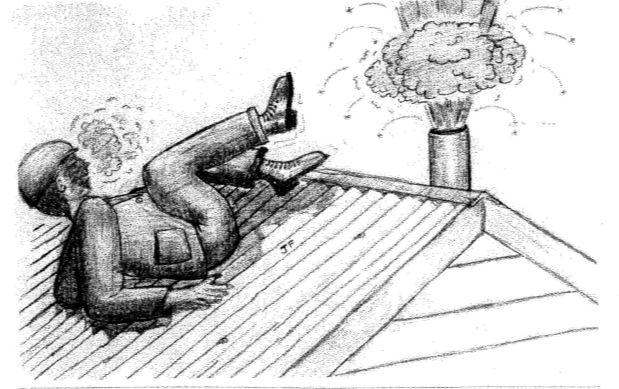

I’ve just remembered another tale about Charlie. I f you recall our hut’s stove had a pipe through the roof for a chimney. Periodically it used to soot up and , as an agile youngster, I had the job of dislodging it. This I did by filling my pockets with lumps of coal, climb on the roof, and drop them down the chimney. Immediately the blockage was removed an updraught erupted from the pipe, just like a volcano, and you had to be quick in moving out of the way. Even knowing what to expect you were sometimes liable to receive a facefull of soot. For some reason, on this day, Charlie decided to solve such a problem himself. I was driving a dump truck at the time and happened to look towards the cabin. There on top of the roof about to drop a piece of coal down the chimney was Charlie. I was amazed to see this because he was shaped like a barrel, being about four feet six inches tall and approximately the same dimension wide. How on earth had he climbed up there I’ll never know. Anyway, I jumped out of my truck thinking 1 could be of some help, but no, I was too late. Simultaneous with the first lump of coal hitting the blockage there was an eruption of soot that not only covered poor old Charlie, but also, knocked him off balance. He fell backwards, rolled down the apex, and dropped the last eight feet to the ground. 1 seriously thought he would be dead, but no, before I could reach him he got up, dusted himself down and walked away.

Ossie Blackwcll was bald, always had a cigarette hanging from the comer of his mouth and was the garage foreman. 1 remember him buying a brand new car and on the second day from new he stopped for a heavilyloaded hitchiker who slid into the passanger seat without taking his backpack off. The handle of a saucepan made a rip of about eighteen inches long in the car’s roof fabnc. Ossie’s response is unprintable!

Horace Bennet – one of three brothers working at the site – was Ossie’s right-hand man and chief mechanic. He lived on the mountain at Rhosesmor and as a hobby bred a couple of pigs. When he gave up smoking he substituted his habit by eating Polo Mints. It wasn’t long before he began giving the old sow one of these mints whenever he visited the sty, and this is where his problem began. Soon she would not let him in unless he gave her a ‘fix’ and ultimately she cost him a fortune in mints. Another funny thing that occurred to Horace and his pigs was the discovery of a wasps’ nest in the pigsty wall. (I think the pigs had also been stung.) Horace bought some carbide which was a powder used in lighting. When water dripped on it it gave off a flammable gas which, in a small container with a minute jet hole, you put a match to. This gas then ignited and gave you light but in uncontrolled larger quantities it was dangerous. Needless to say, Horace placed a large dollop in the wall, poured water over it, and as it gassed-off, threw a lit match at it. This resulted in a tremendous explosion which blew apart the pigsty. It took him two hours charging up and down the mountain before he finally rounded up his frightened animals.

Able Whitehead of Holywell was a driver and fanatic pigeon fancier. On pay-day, Friday, he would bring one of his trusty birds to work with him in a cardboard box. Pay-packets were distributed at lunchtime and he would take out a £5 note, tie it to one of the pigeon’s legs and release it. His wife, waiting at his loft, would then have money to shop to buy food for tea. We all used to threaten him by.saying that one day we would wait on the hill with a shotgun. You must remember that in those days £5 was a lot of money. In fact, it would be over two-thirds of Abie’s wages.

I started on a rate of pay of 2s. 4d. (12p) an hour and the only way I could improve this was to ask to see the owner, Ted Whitley, for a rise. It was something I did regularly twice a year otherwise my wage would remain the same. I can remember on more than one occasion finding myself thumping his desk to get over to him the point that I was well worth a raise, and in fairness, he always took my point and awarded me an increase of Id. or 2d. an hour. We had no Union and no annual pay rise, just some vague Quarries Act which sometimes brought about a penny or two increase in your take-home pay.

Back to the drivers. Isaac Evans from Henllan near Denbigh had a weather-beaten, rugged face. A great character who was forever singing Oh Susannah in Welsh. Can you imagine this being sung in Welsh! ?

Anyway, during and just after the Second World War he worked for what was called the W.A.R.A.G.. a government run agency that served the agricultuaral industry for the growing of food. Isaac was employed by them as a tractor driver whose main task it was to go around farms towing and using a thrashing box. He obviously had to stay overnight at most farms but told me of the time he bought an old motorbike for £5, which he managed to run for about fourteen months to take him to and from work. Petrol rationing was a problem for everyone but Isaac managed to overcome this by putting into the tank, when the engine was hot, a bottle-full of T.V.O. This was a type of paraffin for tractors which had to have a hotplate specially built into the engine to make the T.V.O. vaporise and thus enable it to fire. This was why the motorbike had to be run until it was hot before introducing it to the petrol. However, there was a drawback with this. There was a danger that the bike would catch fire. When this did happen Isaac would extinguish it with wet leaves or grass from the roadside and then continue his journey. Of course he could only get away with this for so long. One day as he ncared hometh e motorbike again went on fire only this time he could not save it and it burnt to a complete wreck. But you know what they say, ‘Every cloud has a silver lining’, In Isaac’s case his insurance company paid him £7 compensation; two pounds more than he had paid for it!

He told me another tale which swore was true. Arriving late one afternoon at a farm of a widowed Mr. Williams and his son, which he regularly visited to do some threshing, he immediately set to work in order to benefit from as much daylight as was left. With it being an overnight stay he later entered the house and was beckoned to the table where a plate of bacon and eggs was placed before him. He thanked his host and asked him how he was – at the same time noticing that he was eating a bowl of hot bread and milk. ‘Not too good,’ came the reply inbetween mouthfuls. T have had an awful bad stomach for months and I am being sick all the time.’ No sooner had he got the words out than up came his bread and milk. He cupped his hands under his chin and caught it, at the same time shouting, ‘Puss. Puss. Come on Puss. It’s no use wasting food Isaac. The cat can have it!’ The bacon and eggs did not taste the same afterwards.

It was Ralph Prince Jones of Mold who drove us to and from work most of the time in an old ex-army Canadian Dodge wagon with that ‘hut* on the back. He was a staunch Sunderland EC. supporter and used Pet and Flowerpot as nicknames for Charlie, and because Charlie was too short to climb into the back of the truck Ralph used to put his shoulder under his backside and heave him up over the tailboard with a, ‘Come on me Old Flowerpot. Come on Pet..I’ll help you.* More than often Ralph would start off before Charlie had had the time to regain his feet and he would be forced to stay there on his back until we reached Mold.

On Pay-day Ralph would also take orders for chips from Warburton’s Chippie in the High Street and I remember one particular Friday when he arrived from town, on chance, with five bags and not one of us had put in an order that day. Furthermore, we were just walking out of the cabin when he arrived. Dispondently, Ralph told ‘Pet’ they were all his. Charlie immediately placed them near him on the bench, guarding them like a wild animal protecting its meal. At that point a driver walked in and asked for just one to taste. He was given a firm no to which he replied by running to the bench and continually sitting and bouncing upon them until they were a mash. Of course, the cabin was emptied, chips and all.

Another person I still think about was a chap from Birkenhead named Albert Hopwood who had his own haulage business and who used to come daily to us for sand and gravel. His son Tony is still in that business. Albert would never be seen without his dog Toby, a nasty long-haired Jack Russell terrier which its owner had spoilt like a child. Once Albert had forgotten to bring Toby his lunch and popped into a butcher’s for a pound of the best liver for its dinner. He then drove into the countryside and parked at the first layby, climbed over a style to a field and unwrapped the meat for his friend. The dog reacted by cocking his leg over it and walking away. Annoyed in the extreme, Albert picked up the liver and chase the dog all round the field, throwing it now and again at the ungrateful mutt and threatening to abandon him. Albert had a very forgiving nature and I can imagine him, after regaining his breath, forgiving Toby by lifting him back into the cab and continuing on his way to deliver his load. Another thing he used to do with the dog, on odd occasion when the plant broke down, was to get me to start up an old Fordson Standard Chaseside (a front-loading shovel) which often took a good hour to get going, during which time he would be quite content to talk at the weighbridge. Indeed, 1 saw him once wait there four hours without being in the least bothered. However, now and again he’d ask for a load from the emergency stock in the quarry. It was not often that he was refused because we knew what the outcome would otherwise be. He would pick up Toby and put him on the desk in the weighbridge, right in front of Dick Rogers’ nose, and tell him. to ‘Stand guard!’ Then he would walk out and sit in his wagon waiting for the outcome because he knew that the weighbridge office was now at a halt. You could not make out any tickets, answer the phone or , as a matter of fact, anything else. Albert would only remove his dog after I had gone through the saga of starting the old Chaseside, taking Mm to the quarry, loading him, and accompanying him back to the weighbridge; the best part of an hour-and-a half. Meanwhile, Toby still sat watching every move within the hut. That dog would not have stirred for the Queen let alone for Ted Whitley. The whole episode was typical of him and his master Albert. Another character was Jack the Grachen, a farmer who lived a couple hundred yards down the hill from the quarry was about seventy years old when I first met him. Every week he used to visit Holywell Market in his pony and trap which was ever so small. His delight was rearing bullocks which Long the Butcher of High Street, Mold, always bought off him. When one of them was butchered Long invariably kept the best cut for Jack. It may well have been part of the deal. Well, once a week Jack the Grachen made his way up to our cabin to reminisce about ‘The Old Times’ with some of the more elderly workers, namely, driver Pryce Davies and Jack Ben net. I made a habit of listening to them talking about what they used to get up to as young lads before the First World War. It was customary for them to travel around the local chapels every Sunday to sing and take part in village concerts and eisteddfodau . I loved it when one would inquire of another how a certain tune would go. The other would then start humming. His mate then put together a few words, and before you knew it, others in the room had joined in. In no time at all six or seven in the cabin would be singing unaccompanied at the top of their voices. In fact, all voices – ranging from bottom bass to top tenor – all in competition with one another. Glorious sounds that I ‘ l l never forget or want to forget. As I’ve said before Ted Whitley was a hard taskmaster. An instance of this can be seen when he decided to spend money in installing electricity. The sub-station had been erected the trench to be opened to take the cable was reserved for employment when the plant broke down. I remember two men sent to to work in the trench grumbled, as we ail did, because of the unpleasant nature of trying to dig through gravel and boulders. However, they did not refuse to carry out the task but after about half-an-hour they were sacked on the spot for ‘straightening their backs’. I can assure you that is perfectly true. I experienced something of this attitude towards workers when, on a terribly wet day, I decided to go and change my mackintosh for a spare one in the cabin. Having taken the reserve garment off the rail by the stove, holding it in front of the heat to warm, I put it on still steaming. Suddenly a loud voice behind me demanded, ‘What are you doing here Foulkes?’ To which on turning round I replied, ‘ I ‘m changing my coat Mr. Whitley, I’m soaking wet.’ ‘ I f you’re too wet to work Foulkes, then you had better ciock-off and go home!’ And I left knowing he ment it. Another incident of a similar nature came about when I was opening a trench about 200 yards in length and 15 feet deep with a drag-line excavator. After a while I saw Mr. Whitley walking along the trench towards me so when he came near I turned the machine off in order for him to get out. 1 put the bucket to one side so that I could also get round the back of the excavator, by means of the running board, to check the fuel with a dipstick. As I was checking it I felt tugging at the bottom of my trouser leg. Looking down I saw Mr. Whitley.

‘ What are are you doing Foulkes?’ ‘Checking the fuel and letting you get oat of the trench Mr. Whitley,’ His repost was, ‘Don’t throttle this engine down Foulkes. Keep it going. 1 will manage to get out of the trench!’ At which point I saw red and retorted, ‘Weil next time you come up this trench don’t come near to this bucket or I will put it on your head!’ I expected instant dismissal, but to my surprise, he just walked away. Working with an excavator provided me with the opportunity of moving to other Whitley sites. One a concrete works at Kinnerton where they made kerbs and flagstones, the other a sand and gravel quarry at Ffrwd. I was once sent to the latter for three months not knowing from one week to the next when I would receive my wages; they being sent weekly from Rhosesmor. It all depended on when a lorry delivered in the Wrexham area. I was often paid a day later than anyone else and this occasionally left us in an awkward situation because the previous week’s wages had already been spent Yes, I did say us . because by this time I was married and living with my in-laws in Aberdovey Terrace, down the Lane End part of Buckley. A couple of facts regarding the foreman of the Ffrwd Works. Once a week he would go to the bank and later on drive to a vantage point on the road opposite the quarry and spy on his workforce with a pair of binoculars. He certainly got on the wrong side of me one day. On this particular morning I woke up to find it snowing with a deep covering on the ground. There was no way I could cycle to Ffrwd in that so I began walking, thinking that once I reached the Penymynydd roundabout, I would get a lift. No such thing. Believe it or not, I ended up walking ail the way to Ffrwd, a mile and a half the other side of Cefn-y-bedd in a terrible blizzard. The story docs not end there though. Come home time the boss would not let the works van run me and another chap a mile or so to the main Mold Road to catch a bus home. Some boss! I had not long been married before I was recalled to Rhosesmor. Our home in Buckley had been condemned as uninhabitable and we were to be rehoused in Padeswood Road. Through general conversation all my workmated knew this and even the foreman and office staff often inquired about the pending move. In those days once a house was declared finished it was the prospective occupant’s duty to clear it out and scrub the premises from top to bottom. As the transfer time approached I kept reminding the foreman I would be taking three days holiday for this purpose; two for scrubbing and the third for moving. Although very supportive of my domestic aims he was growing with uneasiness. He had suddenly realised that during that three-day period neither of the other excavator drivers could operate my machine as it was fitted with a long jib and clamshell (grabbing) bucket. I reminded him that no one had taught me. I had just had to get on with it. My early morning duty at this time was to load ‘Special Sand’ of which the plant only made some 25 tons daily. There was a great demand for this consignment and by 8.30am each morning two or three lorries would regularly be turned away with the advice to try again next day. To assist them with their predicament 1 agreed to scrub out and clean at night and just take the one day off for moving. This delighted the foreman and he could not thank me enough. And when the day came for me to move I did even better. When I heard that the hired van 1 was to have would not be available until 10.30am I reported to work as usually in order to provide our regular customers with the ‘Special Sand’. I was thanked for this and went home to see to my own affairs. It was when I got to work the following day that the trouble started. On arrival the foreman called me to one side and told me that Ted Whitley had gone mad for me taking time off. This I could not believe and thought it a joke. As soon as I spotted the boss I shouted and ran to him. ‘Yes, Foulkes.’ I told him that I had heard he had played hell about me for taking part of a day off to move house. ‘Yes,’ he admitted,’you did not ask me for permission, and you know I rely upon you to be here Foulkes.’ I explained, in detail, all my actions and that I had bent over backwards to help out. His comment was, ‘ I f you’d only asked me I ‘ d have given you a wagon and driver for the night to move your furniture.’ I knew he had stopped this practice some years before after having caught one of his tipping lorries being used to transport a horse from Rhyl! I immediately told him that I had heard of that escapade and its consequences and that I now realised exactly where I stood with him. I went a step further by telling him that from then on he would be advised to put someone with me to learn how to use my excavator as 1 would now be looking for another job. He tut-tutted this and walked away. I followed him and repeated what I had just said to make sure there had been no misunderstanding. That night I called at my brother’s who worked at Padeswood Cement works, and after hearing my story, directed me to see Cliff Parry the foreman. This 1 did and after a short interview and a medical with Dr. Collier of Buckley, was informed that I could start the following Monday. It was still only 10.00am but I decided not to go to work that day. However, 1 did ring up to tell them I would be in for work next morning and they should have my pay-packet ready as I was terminating my employment with them at 5.00pm. You could finish in one hour in those days. When I arrived my mates queeried my actions and the site foreman questioned my decision. Soon the garafe foreman Ossie came across enquiring what had gone on. When I told him the tale he went ballistic and headed straight for the office. 1 can see him now returning after about thirty minutes with that famous fag in the corner of his mouth and grinning from ear to ear. ‘I’ve sorted it out,’ he said, ‘Mr. Whitley has told me to offer you an extra £2 a week to stay’ Now considering that I was only taking home a little over £8 at that time this additional bait was quite a sum. I stuck to my guns. Changed jobs and never looked back because, in my heart of hearts, I knew that soon afterwards 1 would have found myself training someone else for the job, and once that person was considered competent, I ‘d have been dismissed. All in order that he could regain his £2 . I still think that the happiest days of my working life were spent at Rhosesmor Sand and Gravel. I was only twenty-two years old when I finished there in 1962.

Copyright of articles

published in Ystrad Alun lies with the Mold Civic Society and individual contributors.

Contents and opinions expressed therein

remains the responsibility of individual authors.