By Diane Johnson

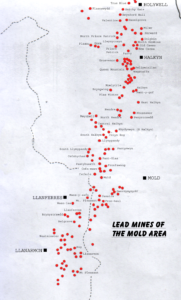

Mold is situated close to the belt of lead bearing carboniferous limestone which runs from Prestatyn, in the north-west through Halkyn Mountain & Maeshafn to Minera in the south-east. As a result of this proximity, Mold has long been associated with the mining & smelting of lead, especially in the 19th century. This schematic map shows Mold in the centre of the main distribution of mines, from Halkyn Mountain, through the Alyn Valley to Llanferres & Maeshafn.

There is evidence of the Romans exploiting this resource when lead was required at their fort at Deva (Chester) for roofing their buildings, water pipes etc. The discovery of a Roman smelting works at Pentre, near Flint & of pigs of lead stamped with the inscription ‘Deceangli’, the name of the local British tribe, support this assumption. There is no direct evidence of the Roman mining effort as subsequent mining activities have destroyed them.

After the departure of the Romans the industry went into decline & it was not until a resurgence of building works under the Normans (this time of castles, abbeys & churches) & during the Middle Ages that there was an increase in demand, but this was on a relatively small scale. There is a record that, in 1280, 24 wagons loads of lead were bought at Mold for Edward I’s castle at Builth. It is not until the beginning of the 17th century that increased interest in the industry is evidenced.

After the departure of the Romans the industry went into decline & it was not until a resurgence of building works under the Normans (this time of castles, abbeys & churches) & during the Middle Ages that there was an increase in demand, but this was on a relatively small scale. There is a record that, in 1280, 24 wagons loads of lead were bought at Mold for Edward I’s castle at Builth. It is not until the beginning of the 17th century that increased interest in the industry is evidenced.

In this part of north-east Wales, mineral rights were being bought up & one of the most prominent families involved in these acquisitions was the Grosvenors of Eaton Hall, Cheshire.

In 1589 the Crown granted the mineral rights in the lordships of Coleshill & Rhuddlan (Halkyn Mt forms part of this) to a William Ratcliffe of London.

In 1597, the same William Ratcliffe was granted a lease of a lead smelting mill & a small plot of land called “Y Thole” by Edward Lloyd of Pentrehobin. (Indicating that the industry was already established).

These two rights were then sold to Richard Grosvenor in 1601 & thus began the family’s connection with lead mining. Around this time they also accumulated the mineral rights in the lordships of Bromfield & Yale in Denbighshire. These acquisitions enabled this family to control a huge swathe of the industry in the Mold area.

At the time of the sale of the Mold lead mill in 1601an inventory was produced & this gives us an idea of how a smeltery functioned. The site’s proximity to the River Alyn allowed the water to power two great pairs of bellows & these were valued at £6-13-4d. Other equipment mentioned was ladles for transferring the smelted lead from the fore-hearth into the one “greate iron moulde” & the 12 “small mouldes”. Shovels & iron bars, for charging the furnace; 10 stampers for crushing the ore before ‘budding’ it; tools, a grind stone & a pair of bellows in the smithy were also recorded. Other items mentioned included 3 pairs of panniers for the carrying of the smelted lead to the warehouse in Chester; 414 sacks of ‘ white coal’ (dried chopped wood), some black coal (charcoal) as fuel for the furnace; a new fire-bottom & a beam & scales for weighing the lead. The presence of some pig lead at the smeltery along with 2000 dishes of ore (each one weighing 66 pounds) at Halkyn & 189 more dishes at the mill show that this was a ‘going’ concern. A rather poignant note is struck by the inclusion of a bedstead & personal effects, probably from the agent’s house which was situated beside the mill.

Other information we have about the mill is that it was worked by Charles & Nigel Coar of Mold with 3 assistants & a Hugh Thomas of Nerquis with 1 assistant. They were to smelt lead weekly at two streams, one to be “wrought in the day & the other in the night”. In 1640 the head smelter, Richard Gerard was paid 5/- per week plus “house & meat”.

[The site is still recalled in the name, Leadmills, an area of Mold, adjacent to the Bridge Inn public house. The housing estate there is called Llys Pont y Fellyn.]

After the lead had been smelted it was carried from Mold firstly to Chester & then on to London. The carriage of the lead was either overland by packhorse or by sea. The relative costs, for example, would be 8/4d or 15/- respectively per ton on a purchase price of £7-10/- per ton.

During the 17th century as the industry gained in importance a new mill was built in 1661 & output doubled but from the 1670’s smelting operations became more concentrated on Deeside, probably due to better transport links by using the Dee. One of the best examples of this is from the early 18th century when the Quaker London Lead Company built a large smelting house at Gadlis at Bagillt.

The Grosvenors’ main interests initially lay in exploiting the reserves on Halkyn Mountain. In 1614 they entered into a partnership with Thomas Jones, a local landowner whose estate was based on Halkyn Old Hall, to exploit the lead reserves. This relationship did not last long & it ceased in 1619 but the Grosvenors, over the following centuries accumulated more & more land & estates on the Mountain. In 1825-26, the Grosvenors built Halkyn Castle along with a new church designed by John Douglas of Chester. They retained these lands until 1913.

From the end of the 18th century the Halkyn estate & mineral properties were administered by an agent at Halkyn while their Denbighshire mines continued to be run from Eaton.

From the early days of this industry, the mine owners found it necessary to ‘import’ labour & expertise from more well-established lead-mining areas as there was insufficient local knowledge. These workers came mainly from Cornwall & Derbyshire & their legacy lives on in many of the local surnames in this part of north-east Wales – such as Hartley, Ingleby, Stubbing & Hooson. Not only did these men bring their talent but they also operated under the laws pertaining to these other districts whereby the miners kept 9/10ths of the ore & giving the owner or lessees the remainder. This was a situation that Sir Richard did not find to his liking & around 1619 he embarked on a course of litigation against the miners who had petitioned that they had been forbidden to work the mines & been forced to sell to the Grosvenors at his price. This case resulted in victory for Sir Richard in the Court of Star Chamber in 1623. The family consolidated their position in 1634 & thereafter they controlled the mining of lead on Halkyn Mountain either by direct working or by the granting of leases. This was not the only time that the Grosvenors resorted to the law or were in dispute with the mining fraternity. There was, for example, in 1698 an instance when Sir Thomas Grosvenor was fighting the Quaker London Lead Company, their lessee. (By this time outside investment in the area was becoming a necessity.) Miners had been removed from the disputed holdings on Halkyn & in the Grosvenor papers there are accounts of legal actions being undertaken. On a more personal note, they also tell of an allowance being made to a miner who had been injured in a “riot at Whitford lane” & the provision of ale to miners when they were incarcerated in Flint jail.

The most famous legal action that involved the Grosvenors, concerned their disagreement with the Lords of Mold in 1752. By this time the easily accessible veins on Halkyn had been worked out & their focus had moved to the Maeshafn-Llanarmon region of Denbighshire where they held the mineral rights of the lordships of Bromfield & Yale. The actual demarcation of these lordships & ownership of these mineral rights had long been in contention. The problem stemmed from the confiscation of the manors of Mold, Hope & Hawarden from the Earl of Derby during the Civil War. The shares of the manor of Mold were subdivided among several individuals & they called themselves the ‘Lords of Mold’. The legal fight that ensued was over which of these two rival factions had the right to win the minerals at mines at Cathole, (Cadole) at Loggerheads. The county boundary had always been obscure, hence the uncertainty. This had not proved very important whilst the land was just regarded as unenclosed waste but as soon as mineral extraction was being contemplated & royalties could be paid to the mineral owners, clear definition of the land was necessary. This whole area was called Mold Mountain. So decades of legal argument followed with a final decision being reached in 1763 when the Court of Exchequer in Westminster decreed that a boulder called Carreg Carn March Arthur (‘the stone of the hoof-print of Arthur’s horse’) was the true boundary. The Lords of Mold had won this case. To commemorate this & to delineate the boundary a monument was erected in the same year on the spot above the stone. This is now regarded as the official boundary between Flintshire & Denbighshire. The actual monument has subsequently been repositioned & can be seen outside Loggerheads Country Park.

[The name Cathole has at least two possible explanations; one that a cat had been found in an old shaft; the other, apparently coming from Cornish miners who originated in the Cornish town of Mousehole, giving their settlement the name Cathole].

(The name Loggerheads has also become synonymous with conflict & dispute.)

The Grosvenors were not the only family to become enriched by lead. Another notable local who benefited was George Wynne, son of John Wynne of Leeswood. He had inherited a field on Halkyn from his mother in 1703 & an

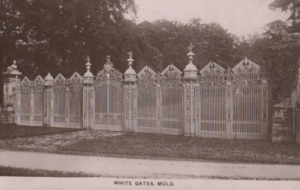

extremely rich vein of lead was found on it. (As this land was privately owned, it was beyond the reach of the Grosvenors!) This resulted in George Wynne amassing a vast fortune, becoming a baronet & an MP. He built a very grand mansion, Leeswood Hall, in 1724 -1726 but more spectacular are the magnificent White Gates which he commissioned from the Davis Brothers of Bersham, Wrexham.

(Another set of gates, the Black Gates, that used to be situated between the two lodge houses on the old Mold – Wrexham road were also commissioned. They are now at the entrance to Tower. These lodge houses are beautifully decorated & are nicknamed, ‘Heaven’ & ‘Hell’).

During the period of Wynne’s prosperity he was in a position to give his young kinsman, the aspiring artist Richard Wilson, sponsorship & support. This allowed Wilson to pursue his career in Italy which he did very successfully. He was later to become one of the leading British landscape painters & was a founding member of the Incorporated Society of Artists, a fore-runner of the Royal Academy. However, he returned to his cousin’s house, Colomendy, near Llanferres, in poverty & broken in health. He died there in 1782 & was buried in Mold Churchyard. Like many other lead mining speculators during the 18th century, George Wynne overreached himself in trying to raise more & more monies to invest in other mines. This had a disasterous result for he died in a debtor’s prison in London in 1756.

The other dominant local mineral owner was the Davies (later the Davies-Cooke family) of Gwysaney. They owned a large tract of land near Rhydymwyn in a loop of the River Alyn & it included the whole of a major vein of lead & several mines were dug to extract the ore. In the late 18th century, one of these mines, the Pen- y- Fron, made the fortune of Richard Ingleby who worked it with only very rudimentary equipment –i.e. pickaxes, buckets, windlass & wheelbarrows! He smelted the ore at the site & then took it just a little further down stream to his rolling-mill to form it into sheets which were then sent to Flint for export. (There are still a few remains of masonry from the rolling-mill on the side of the Alyn). (There are also a series of watercolours by Ingleby that give some idea of the Alyn landscape with all the industrial buildings at this time).

[Rhydymwyn means the ‘ford of the mine’ & this name appears on an Ogilvy road map of 1675, indicating mining activity as early as this.]

Although the main landowners & mineral right holders controlled the industry, because of the perceived “lead rush” many individuals got involved. Leases were granted to miners themselves or groups of speculators including local gentry, business men & even widows & vicars. This was especially true in the 17th, 18th & the beginning of the 19th centuries. Not all these enterprises were successful or profitable. The price of lead was constantly in flux & when the price fell unemployment & poverty followed. It had been hoped, with the beginnings of hostilities against Napoleon, in the 1790’s, that this would lead to an increase in demand & therefore a corresponding rise in the price of lead. These expectations were never realised due to Napoleon’s successes & his economic blockade of Europe. This affected Flintshire very badly as most of their lead was exported to the Continent. Although some was used in Chester

as in 1800 a shot tower was added to the existing leadworks by Walkers Maltby & Company for the manufacture of lead shot for use in the Napoleonic Wars. This tall tower is still a feature of the Chester landscape.

The period of 1810-1815 was very depressing for most of the lead mine owners in Flintshire & this led to Rowton & Marshall’s Chester New Bank at Mold stopping payment in 1810. In 1812 the lead smelters, the Inglebys, went bankrupt.

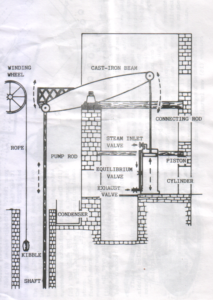

However the other cause for the lack of profitability of the mines was that the workings were having to be dug deeper to reach the lead, as the accessible surface veins had already been exploited & this was hindered by constant flooding. This was a major problem. Because of the porous nature of the limestone, surface water seeped through & accumulated in the lower levels making the mining very dangerous & unproductive. This caused many mines to cease working all together, even the most productive on Halkyn. In the Alyn Valley they tried to pump this water out using water-driven pumps. This was not very efficient & so the latest technology had to be employed, the steam engine!! (These problems were also apparent in the mines at Minera which were following the same pattern as those round Mold).

The requirement of having to bring in this new technology at the end of the 18th century brought to an end the century old system of small scale ventures, dependent on investments of local gentry & by the granting of leases based on royalties derived from the sale of the ore. Capital & investors on a large scale had now to be sought to allow the industry to continue. This also meant the importation of the necessary labour to run the new technology.

Evidence from the Grosvenor records of leases of this time give an indication of the diverse nature of the investors. In 1834 these ranged from local gentry, gentlemen from London, merchants from Manchester & even a merchant, formerly of Liverpool, now of Portau Prince in the island of St Domingo. (Could this have a slavery connection?). Whereas, in 1824 local farmers & miners were the lessees.

Newcomen’s steam engines had long been employed in the lead industry in Derbyshire, the first being recorded in 1717. These early engines were inefficient & in 1769 James Watt patented an improved engine. He then entered into a partnership with Matthew Boulton & they involved the iron-master, John Wilkinson in the production of the cylinders for their new engines. These were produced at Wilkinson’s ironworks at Bersham, near Wrexham. Wilkinson, although mainly known for being involved with iron, was one of the investors in the lead industry in the 18th century & owned mines both at Minera & at Llyn-y-Pandy, in the Alyn Valley. He was so impressed by the quality of the Boulton & Watt engines that he bought several for his own enterprises. (The lead from Wilkinson’s mines was probably shipped via Chester to Rotherhithe on the Thames where it was made into lead pipes).

The effect of the introduction of this new technology can be seen at Maesfafn, where the mine having closed in the 1790’s, was reopened in the 1820’s after a massive injection of funds allowed the water problem to be overcome by the use of Cornish steam engines. (Cornish engines were derived from the Boulton & Watt design). This mine remained open until 1907.

This change in the industry meant that to meet the new challenges new personnel had to be brought in both as miners & engineers. The majority came from Devon & Cornwall & one of the most influential was John Taylor who had

been working at the mines in Tavistock, Devon where he proved to be very successful. He was invited to manage the Grosvenors mines at Halkyn in 1813.

John Taylor originally came from Norwich but due to family connections with the Martineau family, he was given the opportunity to manage their mines at Tavistock at the age of nineteen in 1798. It was here that his management principles of investing heavily in mechanisation & of introducing the latest technologies were founded. This is what set him apart from most other mine managers of the day who usually tried to keep investment as low as possible & look only for a quick profit.

In his first ten years at Tavistock, Taylor emerged as the leader & spokesman for the local mining interests. In 1812 he moved to London & set up other businesses with his brothers. It was probably at this period that he made contacts in London with regard to acquiring finance for future projects. Thus this experience made him ideal recruit to this area of north-east Wales to oversee all the changes required here in the first decades of the 19th century.

He arrived in 1813 & thus began nearly a century of involvement of the Taylor family in Flintshire, both in the mining & the mine engineering businesses.

He rented the newly built house of Coed Du on the River Alyn near to Rhydymwyn. It was a rather grand mansion with a very elaborate Italianate tower. His family remained there, using it as their base to oversee all their local enterprises until 1845. As John Taylor became more & more established as a leading authority on mining, he prospered & this enabled him to have a London residence in Bedford Row during the 1820’s. Here he entertained widely & his most famous guest was Felix Mendelssohn who was later invited to stay with the family at Coed Du in 1829. He was most royally entertained & in gratitude composed his Three Fantasies or Caprices for piano for the three Taylor daughters. The third one, the most famous, is sub-titled the Rivulet & is supposed to have been inspired by the gently flowing river that they used to walk along as they went on their rambles around the hall.

On arrival at Halkyn he was requested to survey & report on the state of the mines there for Earl Grosvenor. He found that although the mines had been extraordinarily productive, most had been worked out to the level of water & were not yielding sufficient ore. Also there was a problem with overmanning with workmen “injudiciously crowded together”. He brought his managerial expertise to the matter & his recommendations were rather radical. He suggested that the existing mine manager, whose family had been involved in the mines for over three generations, should just deal with leases & bargains (rates of payment to the miners) & that mining operations should be put in the hands of an underground manager brought in from another mining district who would have the appropriate experience. The reduction in manpower recommended would mean a loss of over 200 jobs between the two mines but, as the distress that would be caused was acknowledged, he suggested that around 60-80 men could be kept on prospecting for new veins & then dismissed gradually. Taylor felt that if these ideas were pursued the profitability of the mines could be reinstated. Earl Grosvenor agreed with these recommendations & in December 1821 Taylor sent his clerk to the Grosvenor solicitor in London to introduce the new undergroud agent for the Halkyn mines, Absolom Francis. He was a very experienced man & with very glowing references from people who were “perfect judges of what is required”. This was the beginning of yet another Cornish family’s long association with the lead mining industry in North Wales for the next 120 years.

Needless to say, these new rationalisations, including new rules & conditions for annual bargains, were not met with a great deal of approval by the local miners & this led to unrest. The focus of this discontent was directed towards the Cornish men who had been brought in to enforce these new rules. The mine captains, Thomas Williams & James Trenear, were actually driven from the area. (The Grosvenor estate had provided accommodation for all these Cornishmen in the vicinity of the Old Hall, Halkyn, which in the first editions of the Ordnance Survey was even called ‘Cornish Place’). Mining stopped immediately & Taylor urged firm action to be taken by the magistrates against the main troublemakers. In response the miners petitioned Earl Grosvenor but to no avail. However, by these strong measures these Halkyn mines soon became the most profitable in the district. But there was still underlying resentment which flared up occasionally. There was an example of disturbances at the Pen-y-Fron mine over the Cornish practices being introduced there.

These rather harsh reforms enabled the Flintshire industry to withstand a serious price depression during the 1820’s & Taylor was given the credit for this & was honoured at a celebration dinner at Holywell in 1829.

Although working for the Grosvenors, Taylor began investing in & working other local mines throughout the region for himself & held many leases.

From 1823 onwards a process of amalgamation of nearly all the mines on Mold Mountain into one enterprise was undertaken. This company was known as the Mold Mines & it was managed by John Taylor. He  appreciated that a large amount of investment would be required for the purchase of these new steam engines & to improve the water power infrastructure to make these mines profitable. Because of his financial contacts in London he was able to bring a whole new type of investor to this company. Whereas before it was mainly the local gentry investing in their own mines now there was a situation where the investors in the Mold Mines had no local connections at all. In the 1827 report of Mold Mines the list of shareholders include such notables as – the astronomer Francis Baily; Col. Thomas Colby, director of the Ordnance Survey; John Gorwood, later the Duke of Wellington’s private secretary; Dr. Edward Matlby, later Bishop of Durham; Charles Stuart, the British Ambassador to Paris. The largest shareholder was Samuel Hoare, of the banking family. Other investors were the Martineaus & the Hudsons families from Norwich, probably old family friends. They all obviously had respect for the capabilities of Taylor to make this commitment but the company is unlikely to have yielded large profits in respect to the outlay that had been expended.

appreciated that a large amount of investment would be required for the purchase of these new steam engines & to improve the water power infrastructure to make these mines profitable. Because of his financial contacts in London he was able to bring a whole new type of investor to this company. Whereas before it was mainly the local gentry investing in their own mines now there was a situation where the investors in the Mold Mines had no local connections at all. In the 1827 report of Mold Mines the list of shareholders include such notables as – the astronomer Francis Baily; Col. Thomas Colby, director of the Ordnance Survey; John Gorwood, later the Duke of Wellington’s private secretary; Dr. Edward Matlby, later Bishop of Durham; Charles Stuart, the British Ambassador to Paris. The largest shareholder was Samuel Hoare, of the banking family. Other investors were the Martineaus & the Hudsons families from Norwich, probably old family friends. They all obviously had respect for the capabilities of Taylor to make this commitment but the company is unlikely to have yielded large profits in respect to the outlay that had been expended.

One of the lasting legacies of all this investment was the construction in 1823 of a major watercourse channel, known as the Leete.

It was built by Taylor to allow water from the Alyn to be diverted so as to keep the operation of water wheels continuing even during times when the river Alyn disappeared down swallow holes. These water wheels in turn powered pumps which drained the mines further down the valley. The Leete was a considerable engineering feat as it runs for nearly three miles alongside the river. (The Leete Walk follows this old route to this day). Additional leats were also built to service other mines & uses.

Although he was very involved in his enterprises in North Wales & still retained his base at Coed Du, his influence in the field of mine management meant he was in great demand elsewhere & he had interests all over the British Isles & he even diversified into areas abroad such as Mexico.

In 1839 the Taylors leased land on the banks of the Alyn at Rhydymwyn from the Gwysaney Estate where they built a foundry to make their own machinery for the mining industry. Water wheels fed by the River Alyn gave power to all the various processes that went on there. The majority of their output was in fact more water wheels. (All remains of the foundry disappeared under the World War II, Valley Site). The Taylors quit possession of the site in 1863 & the works were resited at Sandycroft on the banks of the Dee. This business remained in the hands of the Taylors for many years. All types of mining machinery, like stamps for the crushing of all kinds of ores, winding & hauling engines & rock drills were manufactured there. It was said that there was no mine anywhere in the world that did not have some piece of Sandycroft equipment. The company also diversified into electrical motors from the 1890’s onwards. It ceased operating in 1925.

Although the family left Coed Du in 1845, John Taylor, followed by his son John Taylor Jun continued to have a huge influence in this area & even after John senior died in 1863, his son continued with reforms & like with his father before him he had to deal with the animosity of the miners. This time the issue was over the reintroduction of the eight-hour day. This problem arose at the Pant y Gof mine in Halkyn when the miners went on strike in December 1865. The Halkyn miners had long been used to working only six hours as this allowed time to pursue other occupations, like being smallholders & farmers or even operating some of the small shafts on the Mountain on their behalf.. This issue was crucial to both sides. Taylor’s argument was that he could not afford to operate the six hour system whilst the miners felt that in the long run, although Taylor had promised to pay more or less 20/- per week compared with 14/- to 17/- for the six hour shift, they would be disadvantaged financially. However, the miners refused these terms stating as their reason that as the mines were ill-ventilated, working longer hours would be prejudicial to their health.

The first disturbance came on January 11th 1866 when around 2,000 miners & colliers marched through Holywell towards Halkyn with the purpose of taking vengeance against the mine captain & those miners who had accepted the new terms. This action so convinced John Taylor that the miners were going to be obstructive that he appealed in person to the Magistrates at the Quarter Sessions at Mold for the protection he claimed he was entitled to. As a result a detachment of the militia, based in Chester arrived in Holywell on the 18th Jan. This force along with constables, with drawn cutlasses, marched to Halkyn to address the miners. This did not resolve the issue & the militia remained in Holywell with the miners remaining on strike. By February, although damage had been done to the mine in the meantime, it was felt that the situation had calmed down sufficiently for the regiment to return to Chester.

The miners then tried to lobby for their six hour shift pattern by petitioning the House of Commons Committee on Mines via their MP, Sir Richard Grosvenor. This did not meet with much success & the strike continued.

As the months passed, a few miners were prepared to accept the new shifts & this so infuriated the strikers that direct action was planned. On May 1st 1866, a large crowd assembled (estimated at anything from 100-1,000!) at the mine & manhandled & bound the working miners. This action was brought to a stop by the police who warned the perpetrators of the legal consequences of their actions so they released the men. In response to this violent act against his miners, Taylor demanded firm action from the authorities & this time they responded in a very efficient manner. On the 28th of May the main body of police assembled at Chester before midnight & were taken by two omnibuses to meet up with a contingent of police from Holywell at Halkyn Castle. They were equipped with sledge-hammers & crowbars & given instructions on leading a coordinated attack on the houses of the suspected ring leaders. A reserve force was to remain at Halkyn Castle under the Chief Constable. The operation was largely successful & 8 men were arrested & taken to the lockup in Mold. Another group of the alleged leaders were also rounded up later.

A Special Magistrates Court was convened in Mold County Hall on 11th June to hear the charges of riot & assault. The town was packed & in case of disturbances in support of the miners, the authorities took the precaution of having a strong presence of local constabulary & a detachment of militia from Chester.

The result of the hearing was to commit fourteen men to the Assizes but because of the possibility of there not being a fair trial in Flintshire, the case was heard at Chester. This gives some idea of how strong feelings were running at this time. The case was not heard until April 1867 when after hearing all the evidence, the jury found four men guilty Two were given six months with hard labour & the others one month with hard labour.

During this period between the trials the strike continued but with an undercurrent of unrest. This resulted in a permanent presence of the local constabulary in the village of Halkyn. They were never required & the strike finally ended in December1866 with the miners agreeing to work the eight hour shift.

Whilst this disturbance was going on the problems related to making the mines profitable was demanding attention. Water was the main obstacle as always & different ways of dealing with it had to be considered. As early as 1818, the most ambitious drainage project ever seen in Britain, the Halkyn Deep Level as it was called , was begun. It involved driving a tunnel from a valley in Flint beneath the mines on the southerly slopes of Halkyn Mountain. It was continued intermittently until in 1875 the Halkyn District Mines Drainage Company was formed under the auspices of the Duke of Westminister & with John Taylor & Sons as the engineers. The company secured an Act of Parliament empowering them to charge levy royalties on mines drained by the level. Between 1878 & 1883, the drainage tunnel was extended to the Rhosesmor. It was then continued to tap into the mines of the Alyn Valley & it reached its furthest point south in 1903.

It was Taylor’s concern about the possible loss of capital to the area as a result of the miners’ unrest of 1866 that he sent a letter to the ‘Flintshire Observer’ to that effect & to explain that the driving of the Halkyn Deep Level would do more good for the region than any other event.

When work began in the 1850’s, its effect was immediate& dramatic. The unwatering of existing workings meant a reduction in costs thus enabling increased profits to be made even in the face of lower lead price. Added to that was the discovery of new rich lodes of lead as work on the tunnel & associated branches progressed. Optimism was high for continuing properity. The mines at Hendre benefited from the drainage level when it reached there in 1893.

The success of this drainage tunnel led the proposal, in 1896, for a second , even deeper tunnel to drain the mines north of the Halkyn District Mines Company area. Work commenced in 1897 by the Holywell-Halkyn Mining and Tunnel Company, an amalgamation of several mining companies.

The tunnel began at Bagllt at sea level & was driven in a south-easterly direction, draining the mines as it progressed. By 1913 it had reached the Halkyn District Mines Drainage Company’s mining area & so an Act of Parliament was obtained, allowing the tunnel to extend into their district & this was achieved in 1919. ( One unfortunate effect of all this tunneling was that at one point the water supply to St Winifride’s Well at Holywell was cut off !! but an alternative source was found)

After World War I, there was a period of stagnation with no further being done extending the tunnel & this resulted in a very depressed industry. In 1928 the various mining & drainage interests came together to form a new company, the Halkyn District United Mines Company & work recommenced on pushing the tunnel onwards. (The world tunneling record was achieved by the workers in 1930 by advancing it 2,037 feet in 14 weeks !!).

This extension had the desired effect of removing the water & also allowing for the discovery of profitable new lodes. For a few short years the area became a major source of lead ore & between 1934-37 1-2% of the world’s lead output came from the Halkyn drainage tunnels.

One of the many features that the miners found as they tunnelled through the limestone was underground caverns. The largest of these was discovered under Rhosesmor in 1931& it contained a lake of indeterminable depth of crystal clear water.

The water disgorged from the tunnel was a useful resource for Courtaulds when they established a viscose rayon factory at Greenfield & could utilize this plentiful supply.

Work was suspended during World War II although the tunnel complex allowed the secret extraction of high quality limestone for specialised glass manufacture by Pilkingtons for the was effort. The Ministry of Defence also found a use for the underground limestone caverns that were now accessible to store quantities TNT .

After the war an increase in lead ore prices prompted renewed activity at the main tunnel face in 1948 from beneath Pantymwyn reaching Cadole in 1957, just yards before the Mold – Ruthin road where the operation finally ceased.

Lead prices were so low at this time that it was limestone that was the important commodity to be worked. This was processed to be used in the agricultural & chemical industries. No lead was mined from 1958 to 1964 until a boost in the price of ore kept a few men working until 1977 by extracting ore from the existing lodes. The workforce consisted of no more than 40 men.

This was the end of the era of lead mining around Mold. It had lasted for several hundred years, surviving all the fluctations of the market until it could no longer compete with cheap imports from abroad due to the high cost of the ore’s retrieval. The smelting industry had already come to an end with the closure, in 1906, of the Dee Bank works at Bagillt. This industry had declined when it had not able to compete with the smeltering works in South Wales & Bristol. The Dee also proved to be unsuitable for the larger ships that were being used to transport the lead. This was due to the problem of silting.

The legacy of the lead mining industry on Mold & district is immense. It is still recalled in some of the town’s place names, like Leadmills & Grosvenor Street. Some of the most common surnames hark back to the miners who came from the likes of Derbyshire, Cornwall & Devon from the 17th, 18th & 19th centuries to give of their expertise & perhaps to make their fortune. Some of the grandest structures in the area like Leeswood Hall with its White Gates, Halkyn Castle & its new church & Coed Du give us some indication of the type of wealth that was generated in the prosperous times. Many important people of the day, in all walks of life, from science & technology to the arts, had some contact with the industry during the 18th & 19th centuries.

The most enduring reminder of the industry can be seen in the landscape around Mold. The rugged contours of Halkyn Mountain with its spoil heaps, its pattern of small settlements & beehive-capped mines are now all that can be seen although it was only in 1987 that the head frames of two of the mines were removed. Along the Alyn Valley there are still the visible traces of the workings with the Leete still in use but this time as a walker’s route. Very little remains of all the engine houses that littered the valley as can be seen from the Ingleby paintings but the Clive engine house between Dyserth & Meliden & the restored one at Minera give a sense of what they must have like. The Milwr Tunnel still excites people’s imagination with its large scale & mystery.

All these remnants of the industry bring alive what it must have been like to have participated in lead mining over the centuries & reminds us of those whose labour made this area of north-east Wales one of the richest lead producing areas in the country.

REFERENCES

Discovering a Welsh Landscape Ian Brown

The History of Halkyn Mountain Bryn Ellis

John Taylor R. Burt

The Lead Mines of the Alyn Valley C.J. Williams

2000 Years of Building Chester Civic Trust

Early Industry in Flintshire Flintshire Record Office

Industry in Clwyd C.J. Williams

Lead Mining in Wales W.J. Lewis

Lead & Leadmining Lynn Williams

The Milwr Tunnel Chris Ebbs

Richard Wilson National Museum of Wales

Flintshire Flintshire Record Office

The Archaeology of Clwyd Clwyd Archaeology Service

Copyright of articles

published in Ystrad Alun lies with the Mold Civic Society and individual contributors.

Contents and opinions expressed therein

remains the responsibility of individual authors.