Ken Lloyd Gruffydd

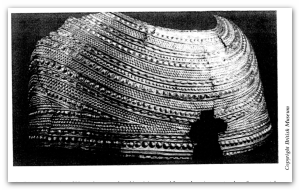

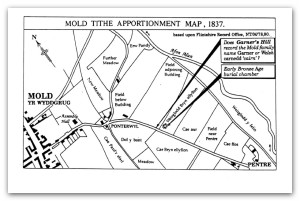

On Friday, 11 October 1833, workmen employed in raising gravel for road repairs near to where the present day Mold Rugby Clubhouse stands dug into a small hillock and disturbed an ancient grave. Amongst the various items retrieved from a stone-like coffin or cistfaen was a ceremonial dress of bronze and sheet-gold that historians have since variously referred to as : breast-plate, cape, cloak, corslet, peytrel and tippet. This archaeological exhibit has been acclaimed as ‘one of the largest and heaviest pieces of prehistoric gold-work so far discovered in Europe, and …. one of the principal treasures in the collection of prehistoric antiquities in the British Museum for more than a century.

The unearthing of a skeleton of ‘above the ordinary stature’ from the same burial prompted the scholar Dr.William Owen Pugh to hail it as the resting place of Benlli the Giant,[1] who supposedly had a fortress at Moel Fenlli on the Clwydian Hills, and whose son Beli is reputed to be buried in Cilcain parish.[2] Although Benlli’s name had not been previously associated with this particular tumulus the deduction reached a century and a half ago fitted in remarkably well with an existing oral tradition. By sheer coincidence numerous eye-witness accounts spanning many years prior to the discovery, vouched to the occasional appearance of a spectral golden giant standing upon the mound. Sightings of this apparition had deterred women and children from crossing Cae Bryn Ellyllon at night; why a certain female began to throw fits, another become crazy, and why a drunkard was scared into sobriety.[3] The feature dug into, Bryn-yr-ellyllon, has been popularly translated as ‘goblins’ hill’ but in view of the above observations perhaps we should not entirely discount the alternative possibility of ‘false gods, idols, spectres’ for ‘ellyllon’?

Let us now consider the archaeological evidence associated with the burial.

Firstly, the tumulus ‘is one of a group of some eight or a dozen sites strung along the middle course of the river Alun, and this group is to be distinguished from the much denser concentration of tumuli on the limestone plateau’ to the north. Its single-grave inhumation places it within the Early Bronze Age period, verified by the discovery of a beaker buried with it.

According to a contemporary report the larger protective stones surrounding the burial comprised of boulders. Whereas this might have been true to some extent there is a distinct possibility that it wasn’t the case with the cistfaen. Today the sole surviving stone from it forms the first of a flight of steps that ascend the motte on Bailey Hill. It is a smooth-cut rectangular block. Another, now lost, was considered regular enough in shape to be installed as a doorstep in New Street. Since the tomb builders were near-con tern poranes of those who raised Stonehenge finding such dressed stonework is not a remarkable achievement. The Early Bronze Age is reckoned to have spanned the period 2300-1200BC, while the most detailed study of the cape to date (carried out forty years ago), narrows the time down to 1350-1250BC.

Experts have relied a little on fact and a great deal upon speculation in drawing their conclusions regarding what is now accepted to be a ceremonial short cape or tippet. For instance, they consider it to have been beaten from one large ingot with its pattern punched in. At the lower end rivetted-in bronze strips acted as strengthener. If the amateur observations of the early nineteenth century are accurate then the cape was worn over a leather, cloth or serge foundation garment. And as it bears evidence of repair work is unlikely to have been new when internment took place. It is a shame really that no ‘ sound pottery’, and only one amber bead (out of about 300 found), have survived. Their form and decoration would have most probably enabled us to identify the cultural milieu from which they originated – and subsequently – provide us with a more reliable means of dating the gold. Amber appears frequently in Bronze Age burials and suggest a trade link with the Baltic such as was the case with the Wessex Culture of southern England. There is no evidence of amber from Irish graves of the same period but on the other hand the goldsmith’s craft was well-established there in the Early Bronze Age. The most authoritative account up to now, however, prefers an European origin to the gold cape, or alternatively, an itinerant craftsman from the north of the Continent.[4]

There are insurmountable problems when it comes to linking the cape with the legendary Benlli Gawr. Firstly, we have no knowledge of the languages spoken in these islands during the second millennium BC. Linguistic scholars suspect the inflow of Celts did not begin until the Iron Age (between c.700 and 300BC) but there is no concensus on the matter. The point is an important one since the name Benlli is of Celtic origin, possibly Irish, and appears first in the early eighth century Historia Brittonum as that borne by a king who occupied a citidal destroyed by St.Germanus de Auxerre, and equated locally with Moel Fenlli ‘Benlli’s bald topped hill’. So far, neither the incident nor St.Germanus’s presence in north-east Wales have been satisfactorily proven. [5] However, the important point in this instance is that St.Germanus did actually visit these shores in 429AD and 447AD; possibly as attempts to re-assert Roman authority (?),[6] providing us with a fifth centurydate for Benlli. That is, if St.Germanus can be equated with St.Garmon of ‘ Alleluhia Battle’ fame. According to specialists the Welsh form Garmon cannot develop philologically from Germanus. The true rendering would be Gerfon ‘loud bellow’, which fits in well with the loud shouting that supposidly brought victory to the Britons at Maes Garmon. Benlli appears in Welsh literature as a semi-mythical character. If he did exist, then his Gawr designation referred to his large physical stature ‘giant’, as opposed to ‘ great’ to highlight his achievements. It is unlikely that anyone would call their enemy great for his military prowess.

The alleged happenings occurred at the beginning of a period in history dubbed the Dark Ages because facts and tangible evidence relating to it are scant. On the positive side, archaeology provides proof that by the time the Romans left Britain in 410AD some of the hilltop forts had already been re-inhabited by Goidelic tribes.

Moel Fenlli was one of them [7], and from what one can discern, Benlli was their principal leader. However, a problem we are faced with is that most of this information comes from literature compiled some three hundred years after the events took place, and is presented in the form of a fanciful narrative, full of Biblical overtones and magical happenings.

Some of the Welsh geneologies place the establishing of the Powys dynasty at about mid-fifth century AD, the individual responsible being Cadell Deyrnllwg.[8] He appears in one of these tales as the person who deposed Benlli of his seignorial position. But,westwards of Moel Fenlli, that achievement is accredited to St.Cynhafael who had recently settled in Dyffryn Clwyd. Basing his poem on an alternative story, the early sixteenth century poet Gruffydd ab leuan ap Llywelyn Fychan of Llannerch related how the holy man brought about Benlli’s death through drowning in the Hafhesb stretch of the river Alun; [9] as opposed to the fireball ending he alledgedly suffered at the hands of St.Germanus.[1O] Both folklore narratives are localized; a characteristic of Dark Age based accounts. The oral tradition associated with this scene incorporates neighbourhood place-names in order to familiarise the listener with the proceedings. For example, Moel Fenlli and nearby Llys Fenlli remind us of Benlli Gawr while in close proximity, each side of the mountain, are Llangynhafal and Llanarmon-y-Ial, consecrated to St.Cynhafael and St.Garmon respectively.

Benlli Gawr, therefore, belonged to the fifth century AD and could not have been the chieftain buried at Bryn-yr-ellyllon in the Alun Valley. Furthermore, the time-span between the two burials could have been as much as 1800 years! In other words, the gold ceremonial cape is over 3,000 years old – and priceless.

It is time to ammend the plaque incorporated into the wall in Chester Road denoting the discovery site.

Footnotes

1. The wording on the present plaque (1923) is less dogmatic,’ …possibly the grave of Benlli Gawr, a British Prince.’

2. A Welsh Triad of the Grave reads : ‘Pieu yr beddyn y Maes Mawr?

Batch ei law ar y lafnawr,

Bedd Beli ab Benlli Gawr.

(‘ Whose grave is on Maes Mawr (Great Meadow)? With proud hand on his sword,’ tis the grave of Beli son of Benlli Gawr.’)

3. E.Davies, The Prehistoric ana’Roman Flintshire (Denbigh 1949), 256-61.

4. T.E. G.Powell, ‘The Gold Ornament from Mold, Flintshire, North Wales’, Proceedings of the Prelusloric Society, 19(1953), 161-79; ‘Trial Excavations at Bryn Ellyllon, Mold’, Flintshire Historical Society Publication, 15(1954-5), 149.

5. K.Lloyd Gruffydd,’Garmon and the “Alleluhia Battle”,’ Buckley, 10( 1985), 34-43.

6. M.P.Charlesworth, The Lost Province or The Worth of Britain (Chichester 1949), 37.

7. J.Morris, Tlie Age of Arthur : Vol.1., Roman Britain and the Empire of Arthur (Chichester 1977), 64.

8. The inscription of the Eliseg Pillar near Valle Crucis Abbey, Llangollen., names Gwrtheyrn (Vortingern) as the one who established the dynasty. Whichever claim (if any) be correct, it should be noted that Gwrtheyrn was contemporary with Benlli and Cadell.

9. S.Baring Gould & J.Fisher, The Lives of the British Saints (1908), II, 254-6.

10. J.Morris(ed.), Nennius : British History and the Welsh Annals (Chichester 1980), 26-7,61., where Benlli is described as a wicked king and tyrant ( rex iniquus alque tyrannus ) .

I rather suspect that the Caeaur ‘ gold field’ adjacent to Bryn yr ellyllon was so named because of the buttercups or rape that grew in it as opposed to an association with the gold cape

Copyright of articles

published in Ystrad Alun lies with the Mold Civic Society and individual contributors.

Contents and opinions expressed therein

remains the responsibility of individual authors.