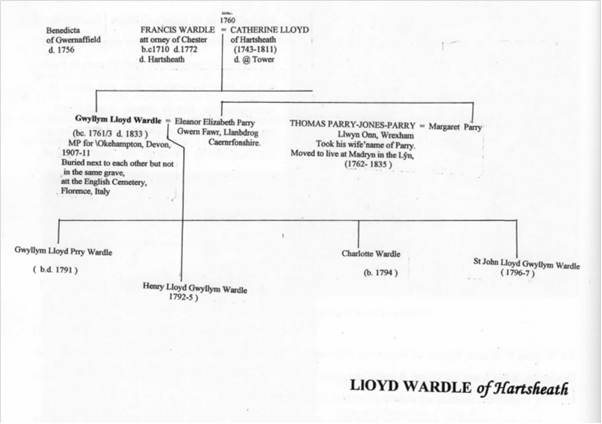

Hartsheath [ SJ 287603 ] is one of Ystrad Alun’s lesser known gentry houses; partly due to it being located at the extremity of the lordship and partly because it is invisible from the roadway, hidden by Pontbleiddyn Wood. It was the ancient seat of the Lloyd family when the reputable attomey Frances Wardle of Chester married the heiress Catherine Lloyd Gwilym c. 1760. A year or so later the union produced Gwyllym Lloyd Wardle,[1] the principal character in this tri-cornered narrative.

Gwyllym was given all the opportunities conferred upon young men from wealthy backgrounds in the Eighteenth Century.

Following schooling at Harrow in 1780 he

proceeded to St.John’s College, Cambridge

but, as was common in those days, did not sit

his degree examinations, and appears to have

left to help to practise law and assist in managing the family estate. Agricultural

improvements and innovations quickly caught his imagination although our first record of him after his university days is a marriage contract he undertook in 1790, between himself and Ellen Elizabeth Parry of Madryn on the Llyn peninsula, daughter of one Love Parry

France’s planned invasion of the United Kingdom saw the rapid formation of regional armed defencibles. In the north-east of Wales Sir Watkin Williams Wynne of Wynnstay (Rhiwabon ) was one to lead the way with his Ancient British Dragoons, a regiment Gwyllym Wardle promptly enlisted in, serving in Ireland where he rose to Captain in 1794, Major three years later and Lieutenant Colonel by 1799.

It is quite possible that by the beginning of the Nineteenth Century the momentum generated by the Agricultural Revolution had attracted him to Llyn since he was actively involved in opposing a plan to bridge the Menai Strait in 1801 , supporting instead, the development of Porthdinllaen as a packet-boat station for Ireland to replace Holyhead. This was hardly surprising since the latter project was the inspired enterprise of his friend William Alexander Madocks who had just established the village of Tremadog on Traeth Mawr; on land regained from the sea. Furthermore, he was a business partner with Madocks at the new settlement, taking advantage of the local wool trade. They had at their disposal a large fulling-mill, dyeing house and a spacious storehouse, the significance of which we will return to presently. Wardle speculated by buying estates in four parishes and was acclaimed by Hyde Hall of having brought to them ‘very beneficial results, and to him, if I am not misinformed, the neighbourhood is indebted for the introduction of the Scotch plough. Upon his ground at Wern I observed some attempt at irrigation. [2]

His drive and enthusiasm saw him elected Sheriff of Anglesey in 1802-3, and the following year, he held the same post for Caernarfonshire. By 1803 he had moved from Flintshire to Cefn Coch and had made yet another move to Wern, near Penmorfa by 1803-4.

Duke of York, who is invariably associated with bungling military operations, has over the past seven generations, been discredited in what has long become a children’s favourite rhyme

The grand old Duke of York.

He had ten thousand men.

He marched them to the top of the hill,

And marched them down again

And when they were up, they were up.

And when they were down, they were down.

And when they were only halfway up,

They were neither up nor down.

This scornful verbiage typified Eighteenth Century pamphleteering, newspaper and cartoon propaganda. Such lampooning by the then political observers and anti-Royalists has, in recent times, been played down. Modern military historians recognise the Duke’s organising abilities and emphasize that prior to being outflanked and forced to sign a Treaty of Alkmaar on 17 October 1799, he had won a memorable battle. He was, in fact, the first general ‘to inflict a major strategic defeat on Bonaparte’! [3] No small achievement in anyone’s army. What was conveniently omitted by political opponents at the time was that it had been pre-determined that all decisions in the field had to be taken jointly by a combined group of British and Russian generals involved. [4] However, the damage had been done and he was never again given the opportunity to command men in the field. Cashiering the king’s son would have been considered too impetuous an action so he was transferred to the War Office; a sideways move into administration where he surprised all his antagonists by displaying excellent organising and managing skills. It has been said that he gave the British army system and direction without which Wellington’s new army ‘would have been still-born. ‘ [5] There is no need to pursue his career, only to mention that his contribution to the ‘war effort’ was significant through his determination that only competent and reliable personnel were appointed to significant posts; soldiery at all levels should be efficiently trained; discipline had to be paramount; communication and supplies were to be prioritised; and the system should be free of political interference. This purposeful person also showed that he had one fundamental weakness – women- which brings us to the third person in this triangular narrative.

Mary Anne Clarke was an attractive courtesan and one of many extra-marital relationships the Duke had become embroiled in. His involvement with this particular ‘loose woman’ began in 1803 and gradually developed into a serious affair, and she, as a divorcee of a bankrupt stonemason, proved to be both remarkably intelligent and wily. Not only did she manage to ascend to the higher circle of society, but more importantly to this exposé, took an exceptionally keen interest in her lover’s national defence affairs. More intentional than unwittingly, he allowed her to be privy to transgressions that took place at the higher levels of army organisation; information she greedily took advantage of. Accusations in the press that the vexed Clarke had, when in liaison with her ex-lover, illicitly sold army commissions for personal gain brought, what had hitherto been privately held rumours, to the public’s attention. Promotion in those days was through purchase, the settlement either going to the retiring officer or, if a new position was being created, into the coffers of the regiment concerned. The charges now laid were that she had personally benefited from such dealings with the Duke’s approval.

Mary Clarke’s extravagant demeanour was such that the constant hand-outs she received from the Duke’s civil list income invariably proved insufficient to her needs. Aggrieved at her perpetual demands he broke up with her in 1805, avoiding potential embarrassment by providing her with a respectable annuity. When he cancelled this arrangement in 1808 she sought immediate reprisal – and this is where Gwyllym Lloyd Wardle re-enters the story.

Wardle first drew serious attention to himself in the House of Commons when he raised the issue of inconsistencies and irregularities in the way army contracts had been concluded during the previous five years; citing the off-hand dismissal of a fair bid made by Scott & Co. of Cannon Row in 1806. Had that tender been appraised on its merit the public purse would have been £22,000 to the good instead of it being diverted into private pockets. [6]

Six months later and he was still persistently pursuing the question of military uniforms, even going as far as to plead with the government to award the clothing contract for the Bedfordshire Militia specifically to the previously mentioned Scott & Co. He made the request on the pretext that the supply firm had provided him with ‘much clear information upon the army great-coat question [7] What he had not disclosed was that he was personally involved in that very trade, being partner with Scott and William Alexander Madocks MP for Boston, Lincolnshire in a textile-mill at Tremadog, some two miles from his home. [8]

Having impressed a small group of pro-active radicals he was enthusiastically encouraged, if not cajoled by them, to pursue his lines of inquiry with greater zeal than previously displayed. Indeed, they were likely to have been the source of some of his discrediting revelations that implicated the Duke of York in administrative malpractices, together with sex scandal accusations that appeared in the newspapers regarding his private life. The bombshell came on 20 January 1809 when the group’s Welsh mouthpiece advised Parliament of his intention to raise both delicate matters in the House. The proceedings at the hearing of 1 February were austere until the flamboyant Mary Anne Clarke made her appearance as the principal witness. Her forthright confession of having used her influence in gaining promotion for certain officers willing to bribe her agitated a good majority of both sides of the House. Despite learning that the Duke had willingly participated in this skulduggery they were too embarrassed to openly condone him, claiming instead that the charges brought forward were unproven.

In fact, they were more concerned with the clandestine way the accuser had obtained his evidence than in seeking justice. Less than twenty-four hours following the twelve-day inquiry the content disclosure of two letters from the Duke to Mrs.Clarke swung the controversy back in Wardle’s favour. Before a packed House of Commons on 8 March Wardle delivered a three hour calculated speech at the end of which he called for the Duke’s dismissal from office. Most present are likely to have appreciated the strength of his case but a significant proportion had too much to lose by dismissing the Duke. Furthermore, they realised that discharging the Commander-in-Chief at a time of serious French threats from across the Channel was an illogic and retrograde step for any govemment to undertake. Hence, a week later the charge of him having misappropriated army funds was defeated by 364 votes to 123, [9] but he wasn’t completely exonerated. Finding himself in a position of consternation, on 18 March 1809 the Duke of York resigned to the utter dismay of the Tories. [10]

The removal of a supposedly ‘untouchable’ was hailed in some quarters as the beginning of political reform, especially in economic terms. The hero of the hour was conferred with letters of gratitude from several municipal councils, he had a medallion struck in his honour and was given the freedom of the City of London, [11] but it was a short-lived triumph. The toppling of a highly placed royal had severely shaken the aristocracy who now feared repercussion similar to that which had revolutionised French society. Wardle was a thorn that had to be removed. On 19 June 1809 an overconfident Wardle submitted to Parliament a scheme for economic reform that was shown to be half-baked. His statistics were demonstrated to be spurious and his debating

skills wanting when challenged by the more eloquent members on the opposite benches. At a time when he desperately needed comfort and encouragement, who unexpectedly re-enters the drama but Mary Anne Clarke. Now whether she was acting of her own volition or was coerced by others is unknown, but her timing was impeccable. She had persuaded an upholsterer named Francis Wright to sue Wardle for not honouring a bill for furniture he had delivered to Mrs.Clarke’s residence, movables the MP had supposedly promised to pay for. There was certainly something suspect about the case because no one less than the Attorney General was appointed chief prosecutor. Not surprisingly, the Honourable Member for Okehampton was found guilty and ordered to settle a bill totalling £2,289; a stiff penalty even for a member of the lower gentry. Wardle was now blind to distraction and in December of that year brought forward a counterclaim of conspiracy against Mrs.Clarke, Francis and Daniel Wright, which he again lost. His popular support held and through selling property, the generosity and efforts of his mother, friends and backers, his legal fees were squared. The radical diarist and future Treasurer of the Ordnance, Thomas Creevey, wrote

‘I can’t bring myself to think that there is anything bad in him, and I have looked at him in all ways in order to be sure of him. ‘ [12]

The stonemason’s ex-wife revelled in the limelight and had already proven herself to be astute, devious and vindictive. Therefore, it comes as no surprise to discover there were more character assassinations pending. In the summer of 1810 she published The Rival Princes that revealed the bitter enmity that existed between the dukes of York and Kent; the latter making no secret of his jealousy and desire of becoming head of the army. Its significance to this brief study is that in an attempt to undermine his brother’s credibility Kent had connived with and rewarded Wardle for his collusion.

Thereafter, the son of Hartsheath’s political career went rapidly downhill with most of his supporters deserting him. Ironically, the Duke of York was reinstated as Commander-in Chief prior to Wardle’s failure to get re-elected by his constituency after Parliament’s summer break of 1812. Almost immediately our disgraced orator took up residency in Kent where he returned to agriculture. It must have been some satisfaction for him to learn of Mary Anne Clarke’s nine month incarceration for libel in 1813. However, further success in farming appears to have eluded him and with intolerant creditors knocking at his door he escaped to France in 1815, never to return. [13] In the 1820s he moved to Florence, Italy, where he died aged 71 yrs on 30 November 1833. He was buried next to his wife at the English Cemetery there. [14] Mrs.Clarke was also obliged to live in exile. She died at Boulogne-sur- Mer, France on 21 June 1852, aged 76 years. They had both outlived Frederick, Duke of York!

Gwyllym Lloyd Wardle is a name that would have undoubtedly graced our history books had he been successful in his efforts to eliminate the improprieties and corruption that took place at the highest echelons of military administration during the Napoleonic Wars ( 1793-1815 ). He may possibly have been ‘the right man at the right place’ when he challenged the aristocratically dominated status quo, but it was certainly ‘the wrong time.’ Britain’s victory in Europe was the government’s principal objective and in that they were repeatedly triumphant. Retrospectively, Wardle had done enough for the surviving parliamentary reformers to take up the cudgels again once peace had been restored.

Notes

- The correct form of his name would have been Gwilym < E. William.

- E Hyde Hall, A Description of Caernarvonshire, 1809-1811 ( Caernarfon 1952 ), 289-90.(ed.) E G Jones.

- P Young & M Calvert, A Dictionary of Battles ( New York 1978 ), Il, 211.

- H C B Rogers, Wellington ‘s Army ( 1979 ), 82.

- A Bryant, The Years of Endurance, 1793-1802 ( 1946 ), 129-30.

- http://www.historyofparliamenton line/volume/1790-1820/member/wardle-gwyllym-lloyd (per 27/10/2012 )

- lb idem

- According to R I Jones ‘Alltud Eifion’, Y Gestiana ( Tremadog 1892 ), 176., during the Napoleonic Wars

- the company of Scott & Wardle sent two vessels with cargoes of soldiers’ uniforms from the Glaslyn estuary

- to France. Both were intercepted and arrested by a British warship for carrying to the enemy. No date given.

- http://www.historyofparliamentonline/volume/1790-1820/member/wardle-gwyllym-lloyd

- http://en.wikipedia.org/Prince Frederick Duke of York and Albany (per 27/10/2012)

- He was proposed by Wrexham-bom Robert Waitham who later became an MP in 1818 and Lord Mayor of

- London in 1823. Dictionary of Welsh Biography ( 1955 ), I, 1012-13.

- http://www.historyofparliamentonline/volume/1790-1820/member/ward1e-gwy11yn-lloyd

- http:historyofparliamentonline/periods/Hanoverian/duke-york-scandal- 1809 (per 27/ 10/2012)

- M Roberts, Porthdinllaen : Cynllun Madocks ( Pen-y-groes 2007 ), 86-7.

Copyright of articles

published in Ystrad Alun lies with the Mold Civic Society and individual contributors.

Contents and opinions expressed therein

remains the responsibility of individual authors.