by David Rowe

(Talk given at the Historic Mold Exhibition in 2021)

In these days of regular drug busts and increasing knife crime, we tend to overlook the fact that in earlier years, people did not have a welfare state or the many charities to call upon if they were in desperate straits. Some of these people resorted to crime just to survive, but they were not hardened criminals. One case I looked at from 1903, had the unusual story of a man, who had set fire to a hay stack belonging to the Alyn Tinplate Works, writing to the police stating that he intended giving himself at 9’o’clock on the following Sunday evening. In his letter he described how he had left Liverpool on the previous Tuesday morning penniless. Seeking work, he went to a number of places including Widnes, Tarporley, Warrington and Wrexham but had to resort to begging for food. On arriving in Mold, he felt suicidal and came up with a plan to do something desperate so he would end up in gaol. As he had lost all interest in himself, he considered this was better than the ‘living hell upon earth’ he was currently enduring. He turned up at the Police Station as promised and, on his subsequent appearance at the Assizes he pleaded guilty and despite the Jury recommending mercy the Judge sentenced him to 12 months of 2nd division imprisonment, but as he had already been held in custody for 2 months the sentence was reduced to 10 months. One sad case among many but it is my intention to talk about the building’s usage rather than individuals.

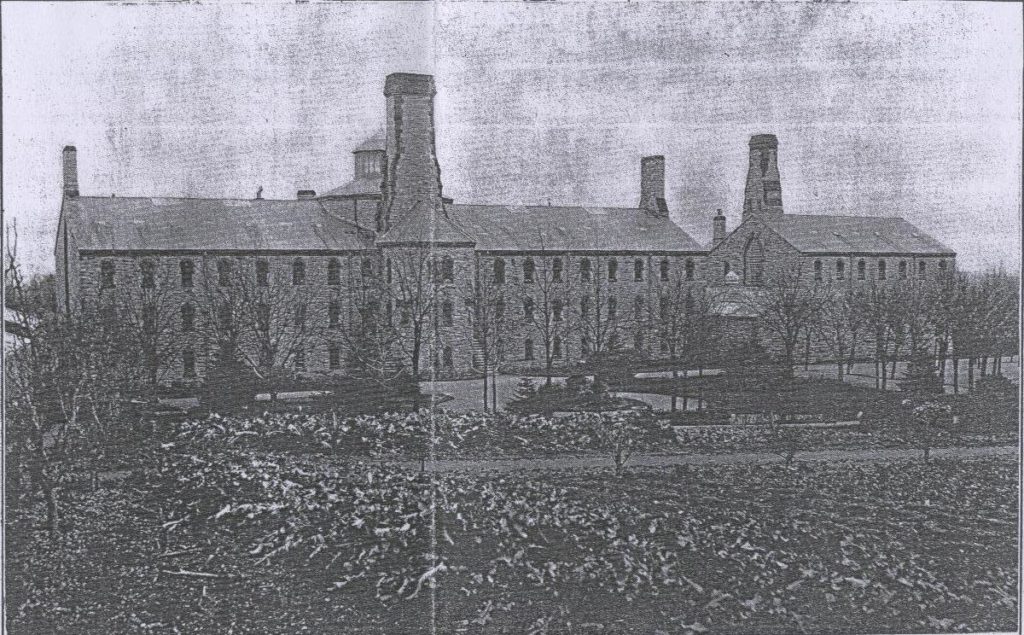

The second of our talks features the building that can be seen in Upper Bryn Coch Lane which, since its original building in 1869-70 has undergone a number of transitions. Although the main gates are generally open, the properties are private residences and therefore I would ask you to respect this by viewing the building from the road.

Prior to looking at the specifics of this unique Mold building, it may be useful to briefly look at the history of Flintshire gaols in general. The removal of a person’s freedom has been used since ancient times as a punishment, although until the late 18c it was unusual to imprison convicted people for long terms. The preferred punishments for serious offences was hanging or transportation. Prisons & Gaols were usually reserved as lock ups for debtors, minor crimes and places where accused awaiting trial were kept. However, by the Victorian era, prison had become an acceptable punishment for serious offenders and it was also seen as a means to prevent crime; it had also become the main form of punishment for a wide range of offences. As towns developed, crime levels increased and authorities became really concerned as to how to deal with this situation. However, it is worth noting that as crime in Flintshire was reported as being low, the Mold gaol was seldom 1/3rd full. There was also a general unease at the number of people being hung, and by the 1830s, many areas in Australia were also refusing to accept criminal transportees. During transportation’s 80 years history 158,702 convicts arrived in Australia from England and Ireland. The net result of this decision was that there were more criminals than could be transported, therefore a major prison building was undertaken. Between 1842 and 1877 over 90 prisons were built or modified, costing millions of pounds. By the mid Victorian Period there were two distinct prison systems operating. The county and shire gaols, comprising of small lock-ups to large ‘County Gaols’ or ‘Houses of Correction.’ administered by Justices of Peace, and our subject falls into the County Gaol category. The second system was run by Central Government and these were classed as ‘Convict Gaols.’ In addition decommissioned naval vessels known as ‘hulks’ also accommodated prisoners. As we will hear later the Prisons Act of 1877, transferred responsibility for all prison establishments to the Home Office. Returning to Flintshire, the first gaol or House of Correction was in Church Street, Flint. Built in early 16c, conditions were pretty horrendous and suicide of prisoners was not uncommon. The following extract from the diary of Nehemiah Griffiths (1690-1738) of Rhual tells us of one other practice used at Flint “23rd April 1715 – Went to Flint. Saw two fellows hanged, one of Newmarket for murdering his brother, the other of Nant Mawr for stealing; the former gibbeted.” The Flintshire gibbet was on Flint marshes and was intended to provide a warning to criminals and to prevent the families removing the bodies for burial. While I lived in Saudi it was said that the bodies of people executed for particularly heinous crimes were placed on crucifixes at the side of the main Riyadh highway. In 1785, a new gaol was erected in the Flint castle yard, some of the buildings were subsequently converted to a drill hall for the 5th Battalion RWF. As early as 1831, suggestions made by magistrates that a new gaol, court house and judges lodges be built in Mold, met with opposition from discontented county ratepayers. In November 1864, the Guardians of the St. Asaph Union proposed raising a petition against a new gaol, particularly with Mold being located in the upper end of the County. A month later a 23 point letter from the Borough of Flint was sent to the Quarter Sessions arguing that the gaol should remain in Flint. Much of the letter was in defence of the Muspratt Alkaline Works. In response, a meeting of Magistrates passed the motion “Flint Gaol suffered from a ‘very offensive vapour arising from the chemical works of Messrs Muspratt and Huntley so the present site was not suitable for the erection of a new gaol. At the meeting of Flintshire Quarter Sessions in April 1865, they confirmed that the new gaol should be built in Mold. Part of the old gaol was subsequently bought by Muspratt’s for £3,200, who converted part of the building into assembly and recreation rooms for their employees, with other parts being converted into housing for employees. Despite all this opposition the magistrates pressed on with their plans and, in April 1866 tenders were invited for the erection of the new gaol, (subsequent records often refer to this as a House of Correction) with details available from the office of Architect and County Surveyor, Mr H.J. Fairclough, St. Asaph. The QS records show that the authority borrowed a sum of £10,200 from the Sun Life Assurance Company, and agreed to insure the buildings for a total of £10,000. QS records in June 1876, show that £16,900 of the £25,000 total cost was still outstanding. This would suggest that further loans were obtained to allow for the building.

In 1867, a quarter sessions was held in County Hall, Mold for the purpose of confirming acceptance of the lowest tender for building the new County gaol. Thirteen tenders had been received, and it was recommended the acceptance of the lowest tender, which was that of Messrs William Thomas and Sons, of Menai Bridge. This was passed with the following resolution: “That the tender of Messrs Thomas and Sons, for £18,808 be accepted, they having provided sufficient security in the sum of £4,000 for the due performance of the contract in a period of two years.” Later in an 1870 inspection report the builder is shown as a Mr Horseman of Wolverhampton, so did Thomas fail to perform his obligations? To allow for materials to be transported to site of the new gaol a standard gauge branch line was connected to the Oak Pits colliery in 1868. From the ending of a siding serving the oil works, a single track line ran across the colliery road before curving west and climbing steadily uphill before terminating at what we now know as Upper Bryn Coch Lane. The line was short-lived (a couple of years) and the still visible pictured track bed became a road by which coal from Oak Pits and other materials/provisions from elsewhere were transported. A visitor to the partially built prison in 1868, wrote to a local newspaper with the following description. “It has been in progress since August last, but only during the last six weeks have fifty men been employed. The whole has been built to the second floor, and gives one an idea of an old baronial castle for substantial work, extent and massiveness. The outside walls consist of large blocks of chiselled limestone, but the inside of firebrick. The dressings of the windows and doors are freestone. All the windows and nearly all the doors and doorposts and the ventilators are of iron and arched with circular or semi-circular ready-made bricks. The whole will be heated by hot-air pipes, and also well supplied with water, as there will be an immense tank of rain water in the rear, besides pipes conveying spring water to all parts. The stairs inside and out are of freestone, so that the whole building will be fire-proof, as with the exception of a few floors and the roof, the materials are of stone, firebrick, and iron. The porter’s lodge will be on the right side of the road which leads up to the centre of the gaol, and the governor’s house, consisting of about nine rooms, will adjoin the porter’s on the right of that, about midway between the road and the gaol. The whole is to be finished by August 1869, and will cost £20,000. The contractors hope to employ during the summer 150 men, providing they can get the materials supplied fast enough. There is a steam engine employed to make mortar, and to drive a saw mill.” On the 27/08/1870 the Cheshire Observer reported on their visit to the new gaol, and while it is lengthy it does give a good description of the now mostly demolished buildings. Left of the entrance doors is the lodge and on the right is the Governors house. Through the two gates and up a flight of stone steps obstructed by a double door with plate glass panels, the bolts of which have been thrown back allowing entry into a passage. On the right of the passage which leads to a central hall we come to the visiting Justice’s Committee room. Next is the prisoner’s waiting room, divided into three compartments by iron railings. Persons wishing to visit are ushered into compartment 1, prisoners in 3 and warder into 2 so avoiding seditious language and giving the prisoner drops of the ‘Dew of Ben Nevis’. The left hand side of the passage leading to the central portion there are two sets of stone steps, one leading down to the prisoner’s reception room, and the other up to the chapel. Further along the passage on the left are two waiting rooms, one for the use of the chaplain, the other for visitors to the prisoners. Passing straight across the central hall we come to the Governor’s office. The room commands a view of the entrances down the passages, and overlooking at the back, the exercise yard, the wheel house, and a large garden. From the room there are bell communications with the female ward and the wheel house. The central hall is octagonal with wings extending right and left marked A and B and containing two tiers of cells. The second row of cells is accessible by a railed stone gallery running around the entire length of the two wings and central hall. The wings are very lofty, and at the extreme end of each is a large mullioned window, made sufficiently secure by iron transoms. The central hall is crowned by a lantern of varnished pine and plate glass. ‘A’ wing contains 29 cells; ‘B’ wing 25 cells. These cells are fitted up in a superior manner with three bolt spring locks by Hobbs, Hart & Co. The bell is rung from the inside of the cell by pushing a spring with a finger or thumb, and which being flush with the wall, it is impossible for the prisoner to destroy. When the spring is pushed an indicator with the cell number painted on it flies open and the warder can see where he is wanted. Two pipes lead to each cell, one for the water supply and the other for gas, the latter being outside the cell throwing its light through a piece of thick plate glass. Artificial light is not required in daylight as natural light is sufficient. Cells are well ventilated. Fresh air is drawn through each by means of a patent scientific apparatus to the amount of 35 cubic feet every minute. The floor consists of blue and red 6” tiles, and there is a fixed water basin and a tier of shelves in each cell. The hammocks, which are made of coir or cocoa fibres are suspended across the cells by means of staples in each side.

From the central hall we get to the male Infirmary overlooking about three acres of ground. Adjoining this are two store rooms, one of which has reminiscences of bygone ages in the shape of a few instruments of torture. Manacles/bracelets or collar/crown or tongue restraint. Ascend from the Central hall by a flight of stone spiral steps to the chapel. Fitted up (theatre wise) with varnished pine seats; the pulpit, reading desk, divisional partition lighted by an ornamental tri-colour gas jets, is capable of seating 60-70 prisoners. Descending the two flights of stone steps we arrive at the prisoner’s reception room in the basement. Consisting of 5 cells and a bath room, where after cleaning to the warder’s satisfaction he walks across the dressing room in a state of nudity where he puts on prison dress. This prevents smuggling of spirits and tobacco or worse still vermin. He is then seen by a Doctor and if free from infectious disease he is taken up to the main wing. From the reception cells we get to the basement of the central hall, on the right hand side is a door leading to a couple of dark punishment cells, with two doors, and a recess between the doors to drown out any noise the prisoner may make. Passing through another door, we arrive at the civil prisoner’s wing for debtors containing a ‘Capital day room and 5 sleeping cells’ with a large piece of ground for exercising. Under ‘A’ wing are 5 general store rooms, a provisions store room, and just outside the kitchen door is a hoist for conveying food to the cells above – hole in ‘A’ wing floor. Kitchen has soup coppers by Hader of Trowbridge and food is cooked by steam. Adjoining the kitchen is the scullery with potato cooking apparatus and slate for washing greasy vessels. In a room or cell away from the others is a double copper, fitted with an India rubber cushion between each, and heated with steam and this is used for cooking and purifying prisoner’s clothes when they first come into the prison. Next is the kitchen yard in which the bath house is situated, containing kneading troughs, etc., and adjoining is the engine house, which supplies hot water and steam to wherever it is needed throughout the building. Not far is a vault containing ventilating apparatus and heating in winter. Apart from any other building is the gas meter house, hastily erected. The female portion is situated at the end of the kitchen – 20 cells in the wing, 6 in the basement, four reception cells, three store rooms besides bathrooms and the female warder’s rooms and bedrooms. The Infirmary is a spacious apartment and looks over the kitchen garden towards Mold. The laundry contains two coppers with cold water taps over each with a drying room. Passing through what will be the kitchen garden we go through a covered way from the female ward to the entrance lodge for females which brings us to the courtyard in front of the gaol proper. Before returning to the central hall we go through an iron gate leading to an exercise yard and the wheel house. The yard contains a large stone circle about 22 yards in diameter round for morning exercise. Near this the wheelhouse, fitted with 2 tread wheels, with twelve divisions and between each wheel is a raised platform for supervision. The wheels pump water into a large tank on the roof to supply the prison. The raised platform also commands a view of 8 cells for breaking stone – hard labour prisoners. The boundary walls are 21′ high and divisional walls male/female 11′ and partitions separating the gardens are 12′ high. No water closets are provided in the prison as patent earth closets are considered more effective. Prison has 30 prisoners scouring cells and other wise beautifying the place.” The Record Office at Hawarden has the Quarter Session minutes and ledgers, and the entry for Jan 1878 details the number of staff along with details of their quarterly salaries and other expenses. As you can see from the slide there was a very small staff.

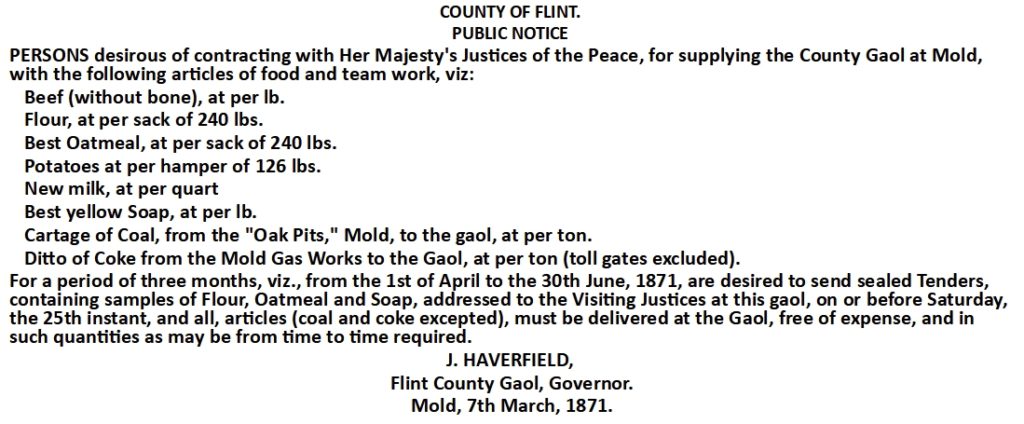

The Governor, John Haverfield, and his wife Annie who acted as the matron, were very experienced. Born in 1831, Haverfield was appointed to Knutsford Gaol in 1854, and in 1865 he was appointed governor of the county prison at Flint, then transferring to Mold on its opening. On closure of Mold in 1878, he was transferred to Carlisle, being promoted in 1884 to Preston, and in 1890 to Walton, where he died in service in 1893. One significant visit was that of Lord Chief Justice Bovill, who after inspecting the gaol made the following entry in the logbook: “I have visited the new gaol this day and have much pleasure in finding the building and all arrangements in a most satisfactory condition a great contrast with the old gaol (Flint) when I visited it on the 5th August 1868, and I beg to congratulate the Magistrates upon having successfully carried out so great and necessary improvement. With the opening of the new gaol the prison population declined such that Court of Quarter Sessions utilized the vacant cells by taking in military prisoners for which a charge was made, thereby making a profit for ratepayers.” Despite the low numbers Flintshire Quarter Sessions turned down an application by Chester City Council for some of their prisoners to be transferred to Mold. One magistrate, Mr Frost, remarked that this must be because our prisoners are kept in excellent style. We will return to the numbers shortly but, first of all, even with relatively small number of prisoners it was necessary to ensure they were correctly fed. As can be seen from the slide, items were put out to tender and by this time, it seems the rail link had been removed. Coal and coke prices had to include for cartage. Note the reference to toll gates. Every quarter, the Governor would report to the Quarter Sessions on prison numbers. In April 1872 he reported that 64 prisoners had been committed to the county gaol, while 65 had been discharged. The number in custody that morning was 18. The greatest number in gaol at any one time during the quarter had been 26, the least 14, and the average daily number, 21. In 1871, we discovered one woman from a notorious Chester family imprisoned with her baby. From one report we can also glean the regularity of some repeat offenders. Sixty per cent, of those in custody were known to have been previously committed to that or other prisons, 10 had been in gaol once before; 5 twice; 1 three times; 1 four times; 3 five times; 1 seven times; 1 nine times; 1 twelve times; and 1 sixteen times. Obviously some people never learned, although it is useful to bear in mind that failure to pay a fine for minor offences resulted in a gaol term. A review of these quarterly reports shows that in the period 1870-1875, the average number of prisoners was 28. During the years 1876 and 1877 the average was doubled due to the gaol taking in military prisoners. With the majority of the cells remaining empty it wasn’t long before our regular anonymous writer signing himself as ‘Rambler’ sent a letter to the local newspapers. His argument was based around Magistrates being unelected, but controlling large amounts of public finance and not subject to real public scrutiny and being extravagant on projects. “They complain about money being spent by School Boards to provide sufficient school accommodation out of the public rates is to be deprecated, but to provide twice the prison accommodation that is necessary is something to boast about. To build a school at the cost of £5 per accommodation is a robbery of the ratepayers; to build a gaol at a cost of £347 per cell, rebounds to the honour of those who accomplished the feat…. There is accommodation for 72 prisoners, accommodation required in this county is only 27 cells, so our magistrates have provided 45 more than they need have done. This means that £15,615 has been absolutely thrown away….” ‘Rambler’ would also have been less than impressed with escapes, particularly that of Joseph Ellis (17) and a deserter from the 22nd Regiment, John Brown. They appear to have loosened bricks or stones in their cells, to have put their arms through, and then used a piece of metal to unscrew the nails fastening the cell lock. After leaving the cell block, they got out through the chapel, women’s cells before climbing over the perimeter wall and going on the run. A reward of £10 was offered for their capture. Magistrates were also less than impressed, and they attempted to claim expenses from the Architects for remedying the defective locks. The Architects declined to pay and the Clerk to the Quarter Sessions stated that they had no legal remedy but there was a moral claim!! Needless to say no recompense was forthcoming. Another escape was a piece of quick thinking on the part of a remand prisoner called George Woodvine. He was employed in wheeling earth into the garden. He threw the barrow down and ran towards the Fron, the Governor followed, but he proved himself too quick, and got clear away. Newspapers reported in February that there was no trace of him, including in his Shropshire home village of Welshampton.

This is also a time when religious adherence was considered important and if the gaol was like prisons I researched for my Mold Riots Aftermath pamphlet, then attendance at services in the gaol chapel, by prisoners, was more or less compulsory. The gaol had its own chaplain, Rev. Thomas Davies, and who was paid £50 for his services, this was increased to £65 when military prisoners were held during 1876 and 1877. An uplift was also given to the Governor of £20, with the proviso that an average daily number of military prisoners confined was a minimum of 15. However, one issue that did arise was the question of services for Roman Catholics. It appeared that as the chapel had not been consecrated, other religious denominations could make use of the building. Permission to use the chapel was also subject to one condition ‘that any symbols or accessories distinctive of that denomination should be removed as soon as the service was over.’ A Roman Catholic Chaplain was appointed at a salary of £10 per annum, and his request for an increase, made three times, was rejected by the Gaol Committee.

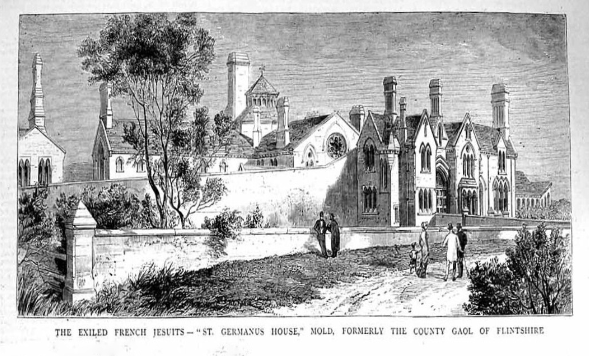

The 1877 PRISONS ACT altered everything, and the Chairman of the Gaol Committee, Mr Wills, stated that the visiting justices had been in communication with the Home Secretary with respect to the transfer of the gaol, and had made application for the full allowance, under the Prisons Act, of £120 for each of the 49 surplus cells; also for an equivalent for the sum received over and above expenses incurred for military prisoners, and for a vacant piece of land close to the gaol, if the Government, in taking over that institution, desire to have it. This payment was not forthcoming as it only applied if the gaol was used for a further two years after implementation of the Act. The Home Office set the pension rates and as can be seen from the slide they were not very generous with their contribution!! In accordance with the Prison Act of 1877, the County was also required to pay into the Exchequer £120 per transferred prisoner. Initially prisoners appear to have been transferred to Chester Castle Prison, but after a time and when Ruthin was recognized as a prison convicted persons were sent to Ruthin. Like Mold, Ruthin was initially considered as unsuitable, but a new wing, based on London’s Pentonville, able to accommodate up to 100, was built at a cost of £12,000. On completion of the new wing HM Prison Ruthin became the prison for the counties of Denbighshire, Flintshire and Merionethshire. The committee also wrote to the War Office asking if they wanted to use the building as barracks or a military prison, but Colonel Stanley, the Secretary of War, declined the offer. The gaol, which had originally been financed by local ratepayers was offered back to Flintshire Quarter Sessions for the sum of £3,278 8s. After discussion the Magistrates decided not to spend further money on the buildings and it was left to the Home Office to dispose of the buildings. So ended one short lived stage in the history of the site and the next stage could not be any different. Mothballed for a couple of years, national and regional newspapers reported in August 1880 that the gaol had been sold for £3,400 to an order of exiled French Jesuits, and two French Gentlemen, one a priest, had visited the premises. Newspapers reported that this was to be their second settlement in Wales, the other at Aberdovey. The articles also highlighted the fact that the buildings had cost the county over £20,000, and ratepayers would not receive any part of the £3,400. Further outrage was expressed at this substantial financial loss to the County with one newspaper correspondent making the following comment, “It can scarcely be supposed that even Jesuits can imagine Wales as a promising recruiting ground,” with one newspaper not holding back, “the building was thrust on the county by one Tory Government and taken from the county by another and that the rates will be saddled with the charges connected with it for twenty years to come.” In September 1880, the building was handed over to the Rev. Francis Xavier Pailloux, who along with two priests, and two lay brothers, took up residence in the renamed the old gaol, St. Germanus House. Germanus being the individual associated with the alleluia victory most of us are familiar with. Workmen were employed to make required changes to the buildings, including enlarging cell and window sizes, as well as building assembly rooms. They also converted the prison yard into a luxuriant garden. The 1891 census listed 53 mainly French students, 13 theology or philosophy teachers, who were all French other than one German, also shown were 13 servants. The servants or lay brothers comprised a number of nationalities; a Turkish/Syrian lithographer; French and Swiss Tailors; French & Syrian Gardeners; a Syrian sacriston; a French house-porter; a Egyptian cook; a German baker; two French cooks/domestic servants; an Algerian butler and a 64 year old Frenchman described as a ‘Commissioner.’ More surprisingly they were all described as English speaking. As a result much interest was shown in an event held at the college in aid of St. David Catholic Schools. The newspapers reported that a large portion of the congregation were protestants, eager to see these new occupants. Interesting to note that the college had, by mid -October 1880, been renamed as St. David’s College. By May 1881, the College housed around 100 students and staff but anti-Catholic feeling resurfaced so much so that the Rector of the College was forced to issue a statement refuting the claims that further communities were being established. The Wrexham Advertiser put its weight behind the community, with the following statement. “We may add that since the arrival of the students from France they have conducted themselves with studied courtesy to the people of the district, and during the cold weather of the recent winter, many of the poor of Mold had reason to be grateful for their well-timed and abundant charity.” Within a short time the college became accepted and reports of their activities regularly appeared in the local newspapers. This included details of the ordination at Mold Catholic Church of a number of Priests and Deacons from St. David’s College by Bishop Mostyn of Wrexham. The Head of the College, Father Pettit confirmed that the ordinands, all French, would be travelling to the HQ of the Jesuits in Egypt, Cairo. In a 1889 guide book of North Wales written by M.J.B. Baddeley and C.S. Ward they describe walking up the road to Ruthin “A little to the left of the road is a Jesuit College (formerly Mold Gaol), and, if our walk be taken in the afternoon, the number of clerically dressed trios taking their daily constitutional, and speaking any language but English, will suggest to us that it is in a flourishing condition.”

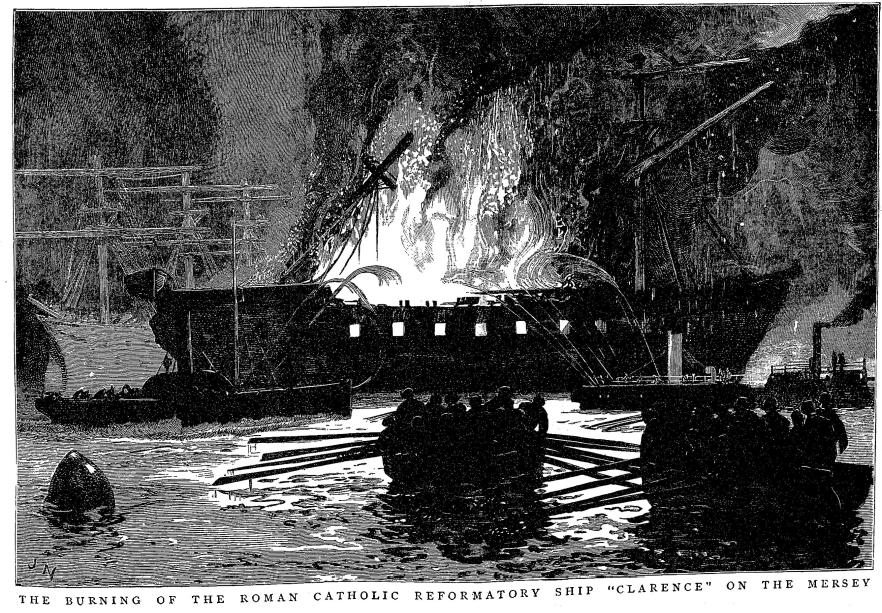

After being in Mold for 17 years the decision was made in 1897, on financial grounds, to close the Mold College and the Chester Courant editionof 29th September 1897, reported on the departure of 20-30 Jesuits departing Mold Railway Station and travelling onto Lyons, with the remainder expected to depart within a few days. So once again this large complex was, apart from a few Jesuit priests, vacant and without any apparent future use. Although in February 1898, the Ruthin Guardians had proposed to the, Boards of Guardians of Wrexham, Corwen, St. Aspah and Holywell that they should purchase the old gaol to receive harmless lunatics, thereby avoiding respectable elderly poor being put in the same ward. Whether they ever seriously contemplated purchasing the site remains an unknown. Circumstances overtook and the story of the gaol moved to its next stage. The 1857 Industrial Schools Act, provided industrial training to young offenders, the Act empowered magistrates to send vagrant children to such certified schools. This power was extended by the Act of 1861 to children under 14 brought before a magistrate for begging, vagrancy, destitution, frequenting the company of thieves, or for being refractory and out of the control of their parents, and to children under 12 charged with a punishable offence but for whom training in an industrial school was a more appropriate sentence. Parents were expected to contribute towards the cost and failure to pay the proposed amount could result in a fine and imprisonment for the delinquent father. Two catholic sons, of one of the five men sentenced to 10 years penal servitude for his part in the 1869 Mold Riots, were sent to gaol in June 1877 for 21 days followed by 5 years in a reformatory. Their crime; ‘fraudulently milking a cow’. While the punishment appears somewhat harsh, it is necessary to bear in mind the boys previous misdemeanors and the extensive criminal record of their father, and to a lesser extent the mother. The court took the view that taking them out of the family home may give them the chance of eventually going on the straight and narrow, unfortunately this did not succeed. The father was ordered to pay 9d per child, but when the arrears reached 15s 9d for each child, he found himself in front of a court in January 1878. He pleaded poverty, but records showed that he had paid various fines for his offences throughout the period in question. The Court ruled that unless he paid the full amount owing he would be sentenced to one months’ imprisonment with hard labour. The Liverpool Catholic Reformatory Association was formed in August 1863 and decided to set up a ‘Ship Reformatory’ for Roman Catholic Boys. A thirty-seven year old warship, the Clarence, was converted and equipped for the purpose and moored on the Mersey at New Ferry, near Birkenhead. On August 3rd, 1864 the ship was officially certified as a Reformatory to accommodate 200 boys, aged from 12-14 at the time of admission. Boys wore naval uniforms and were trained for marine service, there were classes in tailoring, sail-making and net-making. The ‘Clarence’ was to have a troubled history, in September 1882 there was a mutiny on board the ship. Several of the ringleaders received prison sentences, in the same year a boy was brought to court after found trying to set fire to the ship. Then on January 17th 1884, a fire was discovered in the bows of the ship where the oil cans were stored and the vessel was destroyed.

All the 216 boys and seven officers were saved and spent two nights aboard a steamer called Gypsy Queen. They were then housed in a newly built hospital at Bebbington, but the reduction in security enabled sixteen of their number to abscond during the night. An overheard conversation among the boys suggested that the Clarence had been set on fire deliberately, with some of the escapees implicated. 2 weeks later seven boys were found guilty of setting fire to the vessel and were sentenced to 5 years penal servitude. The remaining boys were transferred to the disused Mount St. Bernard Reformatory at Whitwick in Leicestershire in July 1884, although naval style training continued. As may be expected the Admiralty were somewhat reluctant to provide a replacement ship, although in the end they provided a ship called The Royal William, which was subsequently renamed the Clarence and moored on the Mersey under the command of Captain Superintendent E.P. Statham. The ship could accommodate 300 boys and they were transferred from Whitwick on the 19th November 1885. If the authorities thought the new ship and Superintendent would bring about fewer problems they were soon disabused of this thought. Almost immediately the boys mutinied, the Head Schoolmaster, Frederick Potter, was stabbed along with two boys who acted as quartermasters, and boats coming alongside were capsized when the mutineers threw the Clarence’s whalers and launches on top of them. Captain Statham quelled the riot by threatening the boys with a pistol, which unknown to them was not loaded. The 13 ringleaders were found guilty with one boy sentenced to 5 years penal servitude and the remainder given 12 months imprisonment. The Judge was unimpressed with their defence that they had been ill-treated and were given insufficient and bad food. This time the ship survived and life returned to normal, whatever that may be, in a reformatory until 26th July 1899, under the command of the new superintendent, the retired naval officer, Commander Gustavus Yonge. On that day Captain Yonge, his family, 236 boys and Bishop Allen, of Shrewsbury who was on board, in advance of a confirmation ceremony for 24 boys. Unknown to the officers, some of the boys had been stockpiling old rags and other flammable material in the depths of the hold, and as planned during the Bishop’s visit, this was set alight. Quickly taking hold, 2 Mersey steamers Vigilant and Firefly evacuated all on board and they were briefly housed at St. Anne’s Convent and Schools, Rock Ferry before moving to 111-113 Shaw Street, Liverpool. 4 hours after the blaze was discovered the Clarence broke into two and eventually sank. Eventually three ring leaders were identified and found guilty of incendiarism. Recognising the need to find an alternative to the wooden former naval warships, the now unused Jesuit College was by its very construction felt to be a suitable location. To allow the premises to be used, it was necessary to obtain permission of the relevant authorities and it was certified for use on 9th August 1899, and renamed St. David’s Reformatory for Roman Catholic Boys. Despite the obvious building security it appeared that this was no deterrent to some boys. It was reported on the 19th August, 1899 six boys had absconded and while 4 had been recaptured 2 remained at large and as you can see from the Hue & Cry slide, part of the description is the most unusual I have seen on a wanted advert. One boy being a good B flat clarinet while the other was a good E flat clarinet player. Not sure how this would help with their recapture. A seventh boy also made an attempt to escape by clambering down a wall by means of some ivy branches. The boy either lost his hold or the ivy broke, and he fell to the ground, with the result that he sustained severe injuries. However, reference to the clarinet players indicates one of the activities of the boys, the reformatory boasted a band and we find them participating in various local events. In December 1899, they took part in a concert, held at the Town Hall (Assembly Hall), in aid of funds for families of reservists mobilized to fight in the Boer War. On the programme they are described as the Clarence Reformatory Band. Further trouble wasn’t far behind as, on Christmas Eve, 37 boys made a bid for freedom, but they were all captured within a few days, some in the Wrexham area, with the bulk of the escapees caught in the Birkenhead area. Captain Yonge and other officers became aware of general unrest among the boys, with two in particular behaving strangely. As a precaution all the officers were issued with revolvers and a search of the reformatory was carried out. In the cell occupied by the two boys referred to earlier, the searchers discovered heavy bars and other weapons hidden under the bed. Court action came swiftly and seven boys received sentences ranging from three months to fourteen days imprisonment. Despite these ongoing issues the boys still took part in community events. In May 1900, Mold celebrated the relief of Mafeking, the crowd was reported as 10,000. It was also reported that at eleven o’clock the boys of the ” Clarence ” Reformatory Ship, under the command of the popular Captain Yonge, R.N., arrived in town, from their quarters at St. David’s College. The boys, who were sprucely attired in white uniforms, bore Union Jacks, also frames beautifully worked in ‘laurel leaves, and bearing the words “Mafeking,” “Te Deum Laudamus,” (God We Praise You) and other devices. Preceded by their band the boys paraded the streets, and concluded at the Cross where the national anthem was sung. We need to consider that many of these boys were disturbed and a 17 year boy, was charged with inciting another inmate to set fire to the schoolroom; with inciting another inmate to steal a revolver, and with inciting another boy to commit murder by stealing a bottle of poison necessary to poison one of the officers. Following the incident the boy was moved to Ruthin prison, although after evidence from its governor, Mr Parry Jones and Dr. Williams of Mold, the jury found the boy was not in a fit condition to plead. As a result he was ordered to be detained during her majesty’s pleasure.

At this time the establishment was financed jointly by Liverpool Corporation and the Treasury. The life of ‘Clarence Reformatory was not to last much longer particularly when the Home Office changed its philosophy and proposed to withdraw certification from larger Reformatories and change the emphasis on training from nautical to agriculture. In July 1901, it was reported from an interview with Captain Yonge, that the Clarence staff were to be disbanded and the boys transferred to Brentwood Farm, Essex, run by a Roman Catholic Community of Belgian Brothers. Questions were asked in Parliament by a Liverpool M.P. Charles Mc.Arthur regarding this decision, who pointed out that the establishment provided a useful service in training boys for the Mercantile Marine. On average it supplied 50 trained boys per annum and currently there were another 100 boys who had almost completed their training. He was assured that these boys could complete their training and subsequently be available for maritime duties. The comments from Captain Yonge regarding the transfer of boys to Essex turned out not to be true as on the 3rd September 1901, a disused orphanage, Kirk Edge near Bradfield, West Yorkshire was certified as a Roman Catholic Reformatory, catering for 120 boys. Renamed Kirk Edge Roman Catholic Reformatory School, the boys from Mold were transferred to the new premises. So in September 1901, the somewhat chequered history of the ‘Clarence’ at Mold came to an end.

In the meantime it was reported that the buildings were once again being made ready to accept Jesuits who, due to a new French anti-Religious Order Law, were once again to be driven from France. This was the case and at Christmas 1901, Rev. Father Depuis S.J., one of the exiled priests from France preached at St. Winefride’s Church, Holywell, and other priests assisted in other parishes. The college was also opened occasionally for services as well as public concerts. After five years the Jesuits were eventually allowed to move back to France and in 1906, Sisters of the Lady of Charity and Refuge from Caen, paid £8,000 for the property and established a foundation. The sisters took a fourth vow in addition to the normal three vows of religious communities Poverty, Chastity and Obedience. The additional one was ‘to devote themselves to the reformation of the fallen.’ To achieve the requirements of this vow, the sisters opened a laundry and their mission statement was not just to reclaim the fallen, but also to receive girls who were in danger of being lost or who were being brought up immorally. In an effort to make the Foundation financially viable they even advertised locally and also offered to instruct local children in the French language. For the laundry you could have your washing sent to Mold Railway Station where it would be collected and taken to the laundry for processing. The convent was not successful and on the 3rd November 1910, three sisters from the order’s house at High Park, in Drumcondra, Dublin travelled to Mold to bolster numbers. However, the venture failed and sisters returned to their Caen and Dublin houses, while under the terms of the pictured agreement the site reverted back to the Jesuits. There is very little written about the nun’s time in Mold, but sadly the High Park Monastery in Dublin became very high profile. They continued with their vows via a laundry and became infamous as a Magdalen Laundry when, in 1993, the freshly discovered bodies of 155 women and children were discovered by construction workers in the grounds of the convent. Many of the bodies had broken bones, still in casts, and death certificates were not available for a large proportion of these. Other bodies were later discovered in unmarked burial pits and a grey headstone marked “St Mary’s High Park, In Loving Memory Of” features 175 names and dates of death, the first in 1858, the last December 1994. Interviews with survivors also showed that many unmarried girls were forced to give up their babies. A sad and horrendous story, but fortunately we have no signs of such behavior while the order was resident in Mold.

The final stage of the gaol’s public life was during World War I, when it housed a Military Prison. In the early years of the war the British Army was comprised of volunteers, but due to the horrendous loss of life, it was found necessary to introduce conscription. In January 1916 the Military Service Act was passed initially imposing conscription on all healthy single men between the ages of 18-41. Even this wasn’t enough to meet the demands from the front, and this was eventually extended to include married men with the upper age extended to 50. There were exemptions for certain groups including, clergymen, teachers, doctors, railway and dockworkers, miners, farmers and agricultural workers. Those conscripted could appeal to local military tribunals, which were made up of the local great and good, including employers and representatives of organized labour. One group of people who appealed to the tribunals was that of the conscientious objectors. Their appeal was based on religious or other beliefs regarding the sanctity of human life. However, it was believed that tribunals were influenced by their military representatives and were especially hostile towards those claiming exemption on the grounds of conscience. One notable conscientious objector was the 22 year old committed Christian and pacifist, Ithel Davies from Merionethshire.

He was a shepherd looking after the 1,400 sheep on his father’s farm, and although his application to be excused was dismissed, he did receive an exemption from combatant service. This was still not acceptable to Ithel, so when instructed to report to the 4th Battalion RWF, he failed to report and was subsequently arrested on the 28th April 1916. He was initially taken to Wrexham Barracks and Kinmel Park before facing a court-marshal at Park Hall Camp, Oswestry. On the 11th May he was sentenced to 112 days imprisonment with hard labour, this was commuted to 28 days detention at Mold Military Prison. During his imprisonment he was badly beaten, by a Sergeant and Corporal, his nose was broken and he was put a straightjacket for 6 hours (the accepted normal was 2 hours). His case was taken up by the Carmarthen Boroughs M.P., Llewelyn Williams, but his parliamentary questions did not resolve the situation. On release from Mold, Ithel continued to resist conscription and faced two further court marshals in July and November 1916, resulting in spells of imprisonment in Wormwood Scrubs, Winston Green Civil Prison, Birmingham, Shrewsbury and Wakefield. By January 1919, he had served two years of imprisonment, much with hard labour. After the war he became a barrister and was also politically active. In 1935, he was a candidate for the Labour Party but lost to the Liberal candidate, and in the 1951 General Election he stood as a candidate for the Welsh Republican Movement in the Ogwr (Ogmore) constituency. The seat was won by the Labour candidate and Ithel only mustered 631 votes, 1.3% of the total votes cast. Despite his cruel treatment in his younger days he died in 1989 at the grand old age of 95. Whether we agree with his views, I think we must agree that he went through a lot for his beliefs.

Meanwhile the Mold prison continued to function during the rest of the war, with one particular story from September 1916, bringing a smile to my face. A Sergeant Lunn, Private Rimmer and another private from the King’s Liverpool Regiment, escorting prisoners to the Detention Barracks, arrived at Mold Station. They hadn’t previously been to Mold so had no idea where the establishment was located, but after a lot of head scratching one of the prisoners piped up that he had been twice before, so guided them to the prison.

With the ending of the war, the military departed from the old gaol leaving the buildings, still owned it was said by Spanish Jesuits, with no obvious future use. In 1924, the Spanish Ecclesiastical Authorities instructed Adams and Adams so sell the property described as “The magnificent buildings, residences and ornamental grounds” The details include “the main building 160ft long by about 50ft wide, having three terraces of rooms about 85 in number, a handsome chapel on the upper floor capable of seating 200, fitted with pitch pine seats, the lot being in grounds about six acres in extent and all enclosed by a substantial wall about 30 feet high. The property was purchased for £3,000, by the extremely wealthy ship owner, Richard Hughes who lived in nearby Bryn Coch Hall, with the former cell blocks becoming a wonderful play area for his grandchildren. After his death, the old gaol was sold on to a Chester Metal merchant and eventually the bulk of the buildings were demolished, with much of the dressed stone & bricks I understand being used on a Cheshire Housing development. When sold as part of the Bryn Coch estate in 1936 it was estimated that the site contained 6 million bricks and six or seven thousand tons of stone. ADVERTS. The whole site is listed, while the four remaining buildings are now in private hands and I would repeat my opening comments regarding showing respect. So next time you are in Upper Bryn Coch Lane or driving on the by-pass please give a thought to all those who lived, studied, worked or were imprisoned behind the high wall.

Old County Gaol, Upper Bryn Coch Lane.

Timeline

Year Activity

1864 Decision made by Flint Quarter Sessions to replace Count Gaol at Flint Castle.

1866 Tenders invited for the building of a new gaol at Mold.

1867 Tender accepted by Flintshire Quarter Sessions for £18,808.00

1870 New Gaol opened at a cost of £25,333 1s 9d and could house up 95 prisoners.

1871 Lord Chief Justice Bovill visited and reported “all arrangements in a most satisfactory condition a great contrast with the old gaol (Flint).

1874 Governor reported that the average daily number of prisoners was 32

1878 Gaol closed as considered unnecessary under the terms of the 1877 Prisons Act

1880 Site purchased by an order of French Jesuits expelled from France for the price of £3,400. Originally named St. Germanus House by the order it was subsequently renamed as St. David’s College.

1896 Priests and Deacons from the College were ordained by Bishop Mostyn at Wrexham, from where they proceeded to the orders HQ in Cairo. The Head of the College, Rev. Father Pettit, and the 70 students of the college are all French.

29/9/1897 Chester Courant THE DEPARTURE OF JESUITS. On Monday morning an interesting scene was witnessed at Mold Railway Station. Between 20 and 30 Jesuits belonging to St. David’s College, Mold, left for Lyons,where the work carried on at Mold for the past 17 years will be continued. Some of the priests had already left for France, while others will depart in the course of a few days.

The reason of their return to France is to avoid the heavy travelling expenses between the two countries. In consequence, the huge building which the Jesuits purchased in 1880 from the Flintshire county authorities, and which was for some time used as a jail by the county, is again to be vacated.

16/2/1898 Chester Courant PROPOSAL TO ACQUIRE OLD MOLD GAOL. At the meeting of Ruthin Guardians on Monday, Mr. Hy. Williams presiding, the Clerk (Mr. R. Humphreys Roberts) stated that he had had as yet no replies from Boards of Guardians in the five counties to the request he

had sent out by order of the Board in reference to the suggested provision of a separate building to receive harm- less lunatics, and so avoid keeping them in the same wards as the respectable elderly poor. He understood that the Jesuit College at Mold, formerly the Flintshire County Gaol, was to be sold next month, and if the various Boards

of Guardians were to move with a view to acquiring it, they should come to a decision without delay. It was ultimately agreed to request the guardians of Wrexham, Corwen. St. Asaph, and Holywell to decide at once whether they would take part in it, with a view to negotiating for the purchase of the building at Mold.

26/7/1899 Boys from the Clarence Reformatory ship based on the Mersey, is burnt out by six inmates, and the reformatory is moved to the college for 12 months.

17/8/1899

3//09/1901 Boys transferred to Kirk Edge,near Bradfield, West Yorkshire.

12/1901 Jesuits once again barred from France and return to Mold.

1906 Sisters of Our Lady of Charity from Caen (founded 1641) took over the College, paying £8,000.

3/9/1910 Sisters from High Park, Dublin and Bitterne, Southampton

joined the foundation and opened a laundry. The foundation failed and the sisters returned to their mother houses.

1914-1918 Used as a military detention centre and prisoners included

Welsh conscientious objectors. The most notable being Ithel Davies of Tafolog, Merionethshire.

1918-1924 College is listed as being unoccupied.

1924 College offered for sale by public auction on the instructions of the Spanish Ecclesiastical Authorities.

Auctioneers Adams & Adams. Purchased for £3,000 by Liverpool ship owner, Richard Hughes of Bryn Coch Hall, Mold.

The cell blocks were subsequently demolished and the dressed stone was re- used on a housing development in Cheshire. The remaining four buildings of the Grade II listed property; Governor’s House; Warders office & accommodation; workshop and laundry are now private residences.

David Rowe 24th June 2021

Copyright of articles

lies with the Mold Civic Society and individual contributors.

Contents and opinions expressed therein

remains the responsibility of individual authors.